By Marcus Cassidy

cassidym@grinnell.edu

One of the best things about having an Android is that I was spared from Yik Yak. Even though I’d heard of it in passing when during the first few months of the year, I hadn’t directly experienced Yik Yak until fall break since the app is not compatible with my Android. I like to classify Yik Yak into its three common uses: doxxing classmates, commenting on the current shitshow that is the contemporary world and what can only be described as “hornYik Yak.” You haven’t experienced hell until you’ve seen someone post their name, room number and Snapchat onto a social media app in a desperate plea for attention.

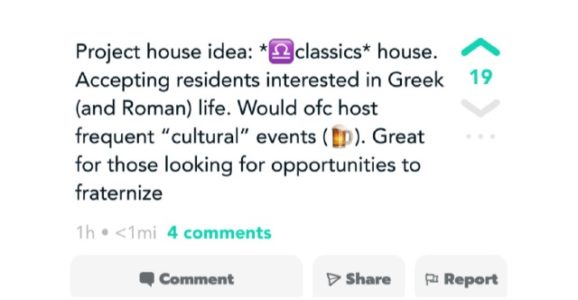

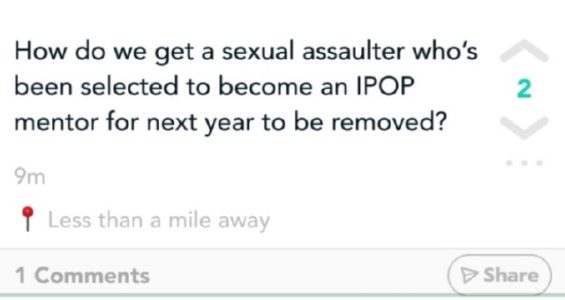

Still, I’d have to say that my general exposure increased exponentially due to the lack of actual recreation on campus back then. Yik Yak was a blissful escape from boredom, until it suddenly wasn’t. Nothing kills your enjoyment for something more than a vibe switch from “Classics House” to sexual assault allegations (see pictures below). Yik Yak was made as a communal forum to make relatable jokes and occasional hot takes. Sometimes, it does an amazing job. However, Yik Yak routinely finds itself used for more serious issues than it was meant to handle, and it’s slowly become one of my least favorite parts of the college experience.

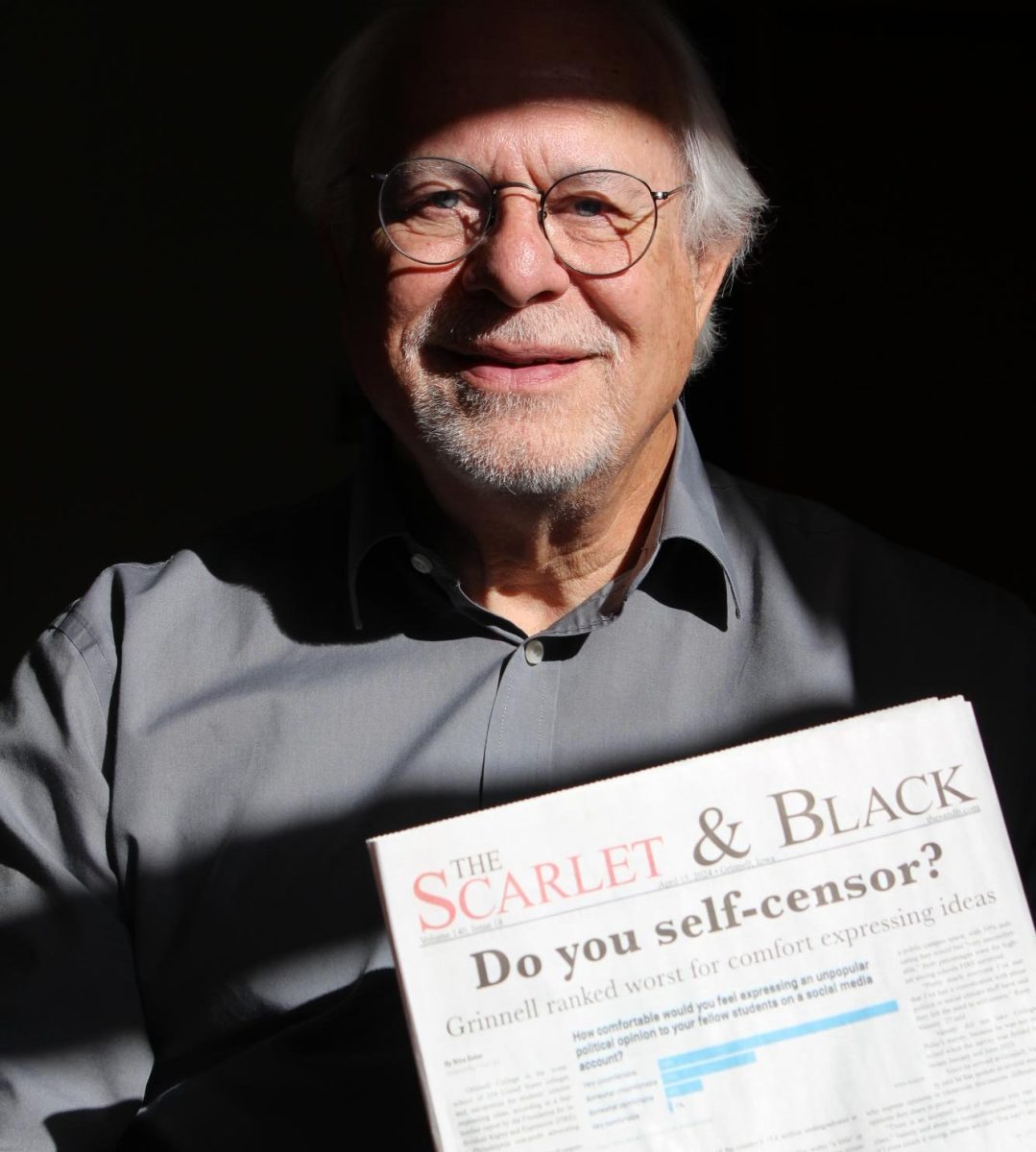

This year doesn’t mark Yik Yak’s first time around the iOS app store. Yik Yak was originally taken down in 2017. Its popularity comes from its two most problematic traits: anonymity and proximity. This dangerous combination leads to an overly expressive echo chamber of bad takes and harassment. In its original incarnation, the app was routinely used on college campuses across the country to spread racist threats and bigotry.

In an article published by the journal Computers in Human Behavior, several researchers argue that “cyberbullying is perpetrated using electronic communication methods and is often characterized by unique features in the online domain, namely anonymity and publicity.” The sheer number of full names that I’ve seen posted in reference to extremely concerning allegations, sometimes people I know, reached double digits a long time ago.

Since the anonymity of Yik Yak supplies a veil of safety, there seems to be a natural instinct for Grinnellians to use the app as a forum of sorts. I would normally be proud of the public persecution of habitual abusers, bigots and general assholes, but there’s an obvious ethical dilemma here. The lifeless emojis that identify your peers help construct this incoherent web of hearsay. How can I take up arms against the accused when there’s barely an accuser? My desire to believe in my peers is constantly forced to battle my hesitation to falsely incriminate.

I get it. With a war in Ukraine, a pandemic, a mysteriously useless endowment and a lacking title IX system, the anonymity of Yik Yak provides an escape from an unpleasant reality. As someone who completes code ciphers in their free time, I certainly have no right to be the fun police. Yik Yak has the ability to produce a humorous communal space for a community that is struggling to reinvigorate its campus life. It allows us to poke fun at our “liberal muzzles” (yes, I know the original poster, and yes, they deserve more credit) and laugh together. However, there’s no bigger enemy to a healthy campus culture than a judgmental atmosphere that keeps people in line through threats of social harassment.

Professors Mary C. Murphy, Kathryn Boucher and Christine Logel conducted research on campus culture at six universities and ultimately argued that “when students don’t feel like they belong, the opposite is true, and they can become disengaged and disconnected.”

At a college with less than 2000 students, we see a proportionally large number of our peers on a daily basis. The occasional funny joke can’t counteract the immense psychological strain that comes from seeing your name anonymously posted in a negative light. It makes you paranoid when you feel judged and scrutinized every day.

I’m not really here to criticize “cancel culture” and defend potential abusers. Rather, the problem is that the existence of issues like these comes from systemic issues in our campus culture.