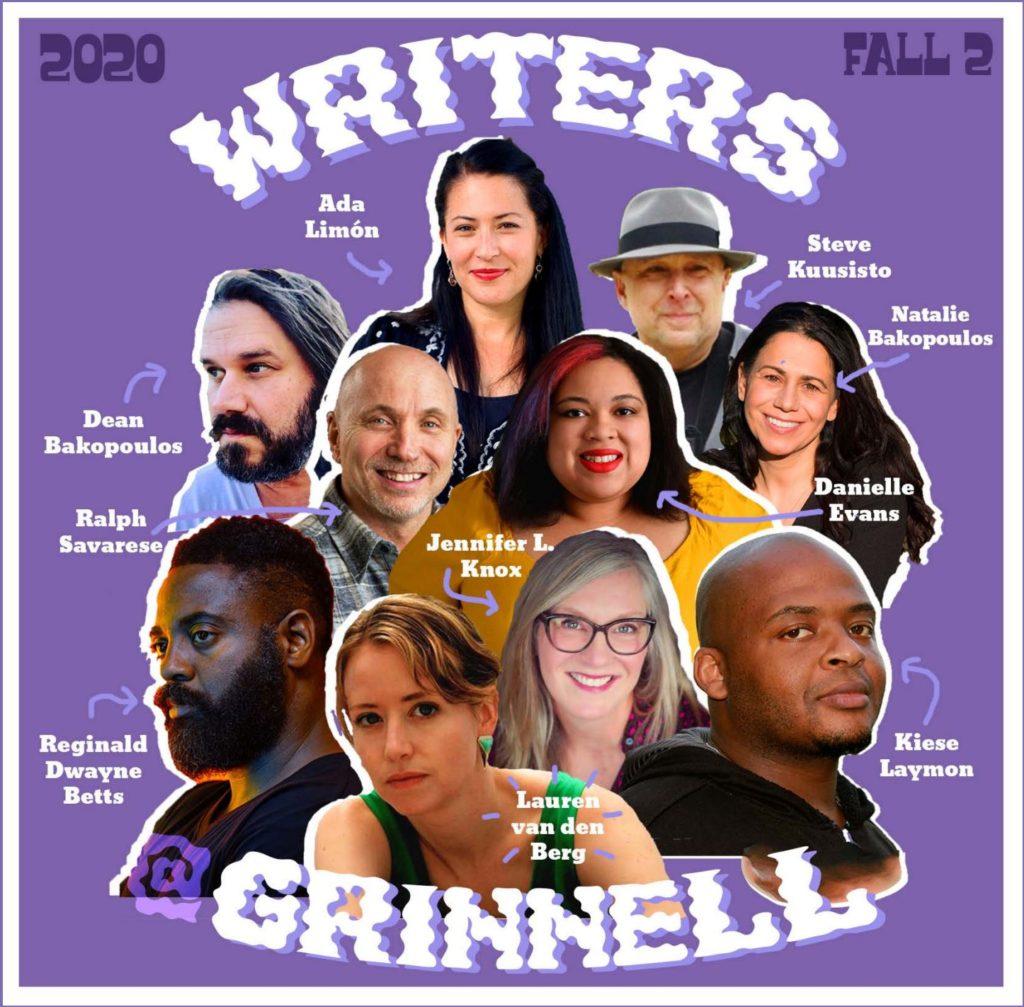

Grinnell College, in partnership with the Iowa City bookstore Prairie Lights, hosted 10 writers over the course of this term to share their work and engage in conversation about craft and life. The five virtual events followed the theme of “Literary Friendships,” as each event paired two writers, friends, siblings or colleagues who read from their most recent work and responded to questions from their virtual audience.

Ralph Savarese, a professor in the English department at Grinnell College, and Stephen Kuusisto each read selections from their newest poetry collections: “Republican Fathers” and “Old Horse, What Is to be Done?” respectively. Ada Limon and Jennifer L. Knox, close friends since graduate school, bounced poems back and forth from their most recent works: “Bright Dead Things” and “Crushing It.” Dean Bakopoulos, author and Writers @ Grinnell director, chatted with his sister Natalie Bakopoulos, who read from her recent novel “Scorpion Fish” and reminisced about their familial connection to Greece. Authors and friends – who met originally at a previous Writers @ Grinnell event – Reginald Dwayne Betts and Kiese Laymon both read excerpts from recent works: Laymon from his book of essays “How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America,” and Betts’ piece “Kamala Harris, Mass Incarceration and Me,” published in The New York Times. The last event featured Danielle Evans and Laura van den Berg, both novelists and short-fiction writers, who read from recent works “The Office of Historical Corrections” and “I Hold a Wolf by the Ears.”

The S&B’s Nadia Langley attended each of this term’s Writers @ Grinnell events and compiled this selection of quotes from the authors, each reflecting the times we’re living in and the experience the authors brought to bear. The writers’ easy humor and sage advice transcended their separate Zoom events and when placed alongside one another, reflected the free-flowing conversations enjoyed by all who attended F2’s installment of Writers @ Grinnell.

On forming a collection of poems or short stories

Laura van den Berg: There are a lot of collections that don’t necessarily have sort-of really explicit thematic resonance, but I think in my favorite collections there’s always kind of like a unifying aura. There’s a sense of stepping into a world with its own sensibility, its own energy and aura and rules, in a way. And even in collections that aren’t necessarily united by character, place or theme, or don’t have those very explicit through-lines, there is still that kind of governing sensibility, and I think I see a collection not just as kind of a gathering of stories written over a specific period of time, but as a chance to build a world. And I think order is a really important part of how a reader moves through that world.

Jennifer L. Knox: In this collection [Crushing it] it feels like a very hard leap from poem to poem. … I wanted it to feel like changing TV channels.

Stephen Kuusisto: I remind myself that I can’t always get it right, that these poems have little lives of their own. They come from often mysterious places that I didn’t understand when I set out to write. One definition of the lyric poem is that it surprises you, right? That you don’t know what’s coming. And that’s the news that stays new for the reader as well as the poet.

On writing and revision

Danielle Evans: There were writers who were like, ‘No, the work is you get up at 6:00 a.m. and you sit in the chair,’ and I was like, ‘Okay, but you know I’m not that writer.’ And I’m happy for those writers, or that kind of writer. Like figure that out early and, you know, set your schedule so it can accommodate that. But I’ve made peace with the kind of writer I am. I know that I kind of write when I feel inspired. … There are more worthy books than I’d have time to read in a lifetime – that existed at the time that I was born – and they make more every year, so there is no urgency for me to make more writing for the sake of making more writing.

Dean Bakopoulos: I think that urgency becomes – it’s the thing you can’t manufacture, it becomes so much a part of the process. Like, at some point your manuscript gets to feel dead, and then all of a sudden the urgency taps in. … The book takes on an urgency when I as the writer finally disappear. And my drafts are so full of me, me, me. It’s probably just the way my brain thinks, partly because I’m, you know, a self-centered mess. You know, I’m the youngest sibling. But then there comes a moment for me, where like the me of it becomes less important than the feeling of it.

Kiese Laymon: I’m just like, thank God for revision, bruh, because if it wasn’t for revision, y’all motherfuckers would not know me, you know, at all. You might know of me from some fucked up shit I did, but you wouldn’t know me.

On when you know you’re done with the piece

Danielle Evans: Shortly after the story has tried to kill you and failed, you should end the story.

Natalie Bakopoulos: You don’t know. I mean, I feel like puking mostly when it goes out. I feel sick and then I feel – the problem is you send something and then you see everything that’s wrong with it. Like that’s the only way I can sometimes see it, is if I start to imagine it through somebody else’s eyes.

Kiese Laymon: I mean, first of all, I never know and like, just the kind of person I am, I just always, I don’t, I expect it not to hit. Like I expect – the shit that I think is going to hit – I expect it not to hit. But when I read “Heavy,” when I read that first section “Train” [in front of an audience] … I just knew that like, I wasn’t wasting writing’s time, I’ll say that. I didn’t know it was gonna hit but I knew, I was like, ‘Oh okay, all this time I put in, I just didn’t waste writing’s time,’ and sometimes you need audience for that shit. Sometimes you need an audience to let you know, you know? You can think that shit is fresh or hot, but sometimes if you don’t share it and like sit in the response, like really sift through the response, you just sort of don’t know. So, I knew that day, that’s when I knew, I was like, ‘Okay, this is gonna hit a little bit more than I thought.’

Dean Bakopoulos: When you don’t think it’s so good. When you think it’s so good it’s still early. But when you think it’s trash, you probably are being too hard on yourself.

On writers supporting one another

Ada Limon: It’s really great to have people who hold you accountable.

Kiese Laymon: Sometimes these deadlines, we be writing to the deadline – even though we can work on a piece for fucking five months – sometimes we just want to be done. And I think, I think I need somebody sometimes to be like, ‘Yo, you done, but do you really like that shit? Do you really, or do you like that you’re done?’ You know, that’s what I need motherfuckers to tell me.

Reginald Dwayne Betts: You got to know your peers in an intimate way to actually learn from them.

Jennifer L. Knox: I wouldn’t give them a poem I didn’t think was talking to people.

On writing during the pandemic

Ralph Savarese: I posted a lot of these poems on Facebook and I published a lot of them, but I also sort of gave up that idea – that overly professionalized idea – of hoarding my poems and only letting people see them when a magazine has certified that it’s fantastic. Posting them and hearing from my friends – and so many of you are on this call – writing a note that said, ‘Thank you for that,’ was actually part of what got me to the next hour.

Stephen Kuusisto: I’m also mindful of the fact that there are people in literary life who have had it much harder than I have. You know, some are still with us, some are ancestors. I look to poets like Langston Hughes for instance, whose work I love, and I take solace and sustenance from their ability to power through times that were even darker than this one.

Natalie Bakopoulos: Specifically at the beginning of pandemic, there was all this talk about remaining productive and becoming expert online teachers and, you know – it’s just – it seems so, so beside the point of what was actually happening. Like, we only have one body, and we have to take care of that body, you know? And so this idea of this – having to be productive during a pandemic – I think everyone needs to give themselves a break.

Dean Bakopoulos: I don’t think you can force the mood right now. The mood for me with writing in the pandemic is always like, ‘Okay, here’s how I’m going to survive these next few days. I’m intrigued by this project, and this will get me through.’ But there’s also days where I don’t think you can. … The pandemic is teaching us a little bit about limitations being a very big part of the creative process.

On writing with current political tensions

Natalie Bakopoulos: I think the political anxieties of the present always inform something you’re writing, and I also think we read things with the lens of the current moment. So even if something was written twenty years ago, we might say – or thirty years ago, fifty years ago – there’s things that are going to feel dated, but we can still talk about them through the lens of now and think about the tensions between those two things.

Danielle Evans: Most of the stories that ended up feeling topical when they came out I had been working on for a long time and they didn’t feel topical to me and so it was more of like a working against, of like, ‘what else is there to read in the story.’ I held on to some things because I was worried that if I tried to publish them in the middle of something, it would seem like they were responsive to headlines or that’s the only way people would have to read them. And I wanted to make sure both that the story had enough room to have the bigger picture questions that would sort of outlast whatever public conversation was happening at that moment – and also that people would understand the sort of work of the story and not to be kind of ripped from the headlines.

On advice for young writers

Stephen Kuusisto: One thing that really helps when you’re starting out writing poetry is to allow it to be a game, rather than a serious weight of all of human history literary temple that sits on your shoulders and crushes you down, you know? And there are a lot of really good games you can play with poetry. One of my favorites, and I still use it myself, is based on a poem by Charles Simic called “Stone.” … In that poem he imagines going inside a stone, and inside that stone is so much richness and strangeness and loveliness and weirdness. And it’s a captivating little poem. And once you read it, do your own version. And it doesn’t have to be a stone. … Go inside an apple, you know, what’s inside there? Go inside an electric wire, what’s inside there? You wind up coming up with all kinds of really interesting, strange stuff. And of course, that’s the stuff of poetry.

Kiese Laymon: I love reading people who are better than me, because I’m not afraid to say, ‘Nobody better than me,’ but I’m also not afraid to imitate them until I can get better. That’s what I feel like with both of you and when Dwayne [Reginald Dwayne Betts] hit me, I’m always like I’m finna be a better person and a writer.

Reginald Dwayne Betts: You write to be a better writer. So much other stuff is just a consequence, and I think I write to be a better person.

Kiese Laymon: Do everything you can in the world to be a better person than you are an artist and realize that in doing that, you might be making yourself into a better artist.

On being a writer

Reginald Dwayne Betts: The hardest part as a writer is to figure out how to move through those different emotional layers, you know, from like the seriousness to the laughter. And to do it in a sentence or a paragraph, it’s almost impossible. … As a poet I think too often we can get into one lane. But I think when you’re an essayist, and definitely when you’re writing fiction, I feel like you got to touch on all of it, you know. You can’t help but to touch on all of it.

Danielle Evans: I’m writing a book for this sort of reminder that constructing narrative is how we find meaning and form a sense of self.

Ada Limon: We’d rather be good people than good poets.