This article is a part of The S&B’s Anniversary Project. See the entire project here.

I got the email at the front of the stir fry line.

Among Grinnell College students, this is a coveted position. The stir fry line can stretch as long as 50 people, winding its serpentine path through the chaos of the lunch and dinner rush. Waiting in that line encapsulates much of what it means to go to Grinnell: the mundane rituals of a small college with a singular dining hall, the constant calculus of the time you have between classes, the short and long bursts of conversation with anyone you happen to see while standing there, how you can be absolutely alone and yet surrounded by hundreds of people.

The email in question was sent out to the entire student body at noon on March 10, 2020. The text was in bold: In light of the spread of COVID-19, the College would shift to distance learning for the rest of the year. “All students are expected to leave campus by Monday, March 23.” That date would later be moved up to March 16.

There were three known cases of COVID in Iowa at that time. Nationally, there were under 1,000 known cases.

Everyone was looking at their phone. I know that older people say that young people are always looking at their phone, but I’ve never seen an entire hall of people looking down at the same time. It was so quiet in the Dining Hall, vibrating with a nervous, tentative energy.

I felt numb. I didn’t really know what to do with the information I’d received, much less with myself. I could feel that something big was happening, not the dimensions of the significance, but the monumental energy of change in the air as a year’s worth of plans disappeared in an instant.

I decided to take some photos.

A year later, looking back at these blurry pictures, I spot Mariyah Jahangiri, also waiting in line for stir fry. She’s standing with her friend Carmen Ribadeneira, both of their heads bent over their phones, angled towards each other as if to verify that they’re seeing the same thing. Mariyah’s hair looks wet, fresh from the shower.

In fact, she tells me when I call her a year later for this essay, she was just starting her day, walking into the Dining Hall to get some food, when she got the email on her phone.

“That’s so crazy, the fact that you captured that,” she says. I can hardly believe it myself.

Mariyah graduated from Grinnell in a virtual ceremony last May along with the rest of the Class of 2020. She’s in Puerto Rico right now doing activist work centered around food justice. Talking over the phone, her at an outdoor bar and me in my family’s house in Upstate New York, we marvel over the existence of the photo, how it conveys the tensions of such a specific moment.

“Do you remember how the student workers were stopping what they were doing and some of them were crying?” she asks me.

I do. Many of the students around us were crying, holding onto their friends or leaning on the fake wood tables. Others were talking quickly and anxiously, standing up abruptly and then sitting back down. As I walked with my plate of stir fry to a date table, I sidestepped a student who had just sat down on the floor, physically leveled by the new information.

**

Our emotions formed their own topography on campus. There was the shifting foundation of anxiety about the larger world and the great unknown of what was to come, the sense that life as we knew it was changing. But there were also smaller, private clusters of loss about personal milestones that would now be delayed, a class trip canceled, relationships just at the beginning that would now face the test of distance.

One day, I took a walk with my friend Abraham through campus, witnessing this landscape. We passed by some seniors from the ultimate frisbee team who had set up speakers near the library. A song I didn’t know blasted across South quad. The setting sun tinged the sky an almost taunting array of pastels. I didn’t know what to feel, there was so much sadness in the air and yet how much of it was right to claim as mine?

Abraham read a part of an email he’d just received from Dean Bakopoulos, his advisor, out loud to me. He said it had helped him process what was going on. Bakopoulos wrote:

“It is okay to be compassionate and worried about the wider world, and to allow yourself some more self-centered grief too. The heart is big enough to worry for the world while it grieves the minor losses too.”

I reached out to Bаkopoulos for this piece, to ask him what he remembers from that week. Speaking to me from his balcony in Los Angeles, he recalls returning from a trip to the city last March to find campus empty.

Bakopoulos calls campus after the students left “a griefscape.”

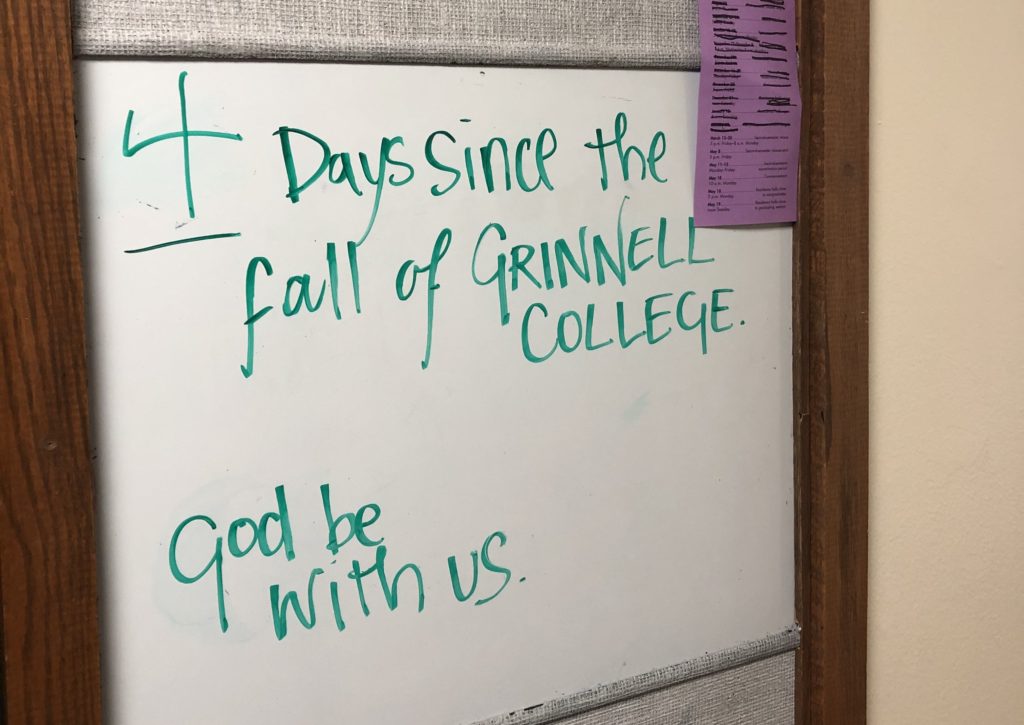

There was stuff piled everywhere. In the lounges, mountains of discarded belongings accumulated: mattress pads, laundry baskets, ramen boxes, astronomy textbooks and golf clubs. Beer bottles and cheap boxes of wine littered the stretches of grass between buildings, remnants of riotous last parties. Students left scrawled messages on the whiteboards in Noyce and outside of their dorm rooms conveying through various phrases the eternal slogan of the dispossessed: We were here.

College, Bakopoulos says, is an experience of “mythic significance,” and the disruption of that time is singularly traumatic.

“I think that high school students and college students had the biggest emotional whiplash,” he said. “I don’t think we as a culture have done a great job of acknowledging that. Your generation will always remember this and be shaped by this.”

**

For Puravi Nath, personal loss intertwined with global context as public health policies drew lines around her range of movement, defining a set of choices more complicated than just “going home.”

“For us it’s more about borders,” Puravi, a fourth-year international student from Kolkata and Bangalore, India, explains. When the College sent out that March 10 email, she and her fellow international students had to come to terms with the pandemic in both Grinnell and their home countries.

The College held a town hall for international students the night of the announcement. The meeting was packed with students from dozens of different countries. It lasted over three hours.

The global nature of Grinnell and the consequences of the College’s broad reach was what ultimately led the administration to announce the shift to remote learning before any other institution in Iowa and before most in the country.

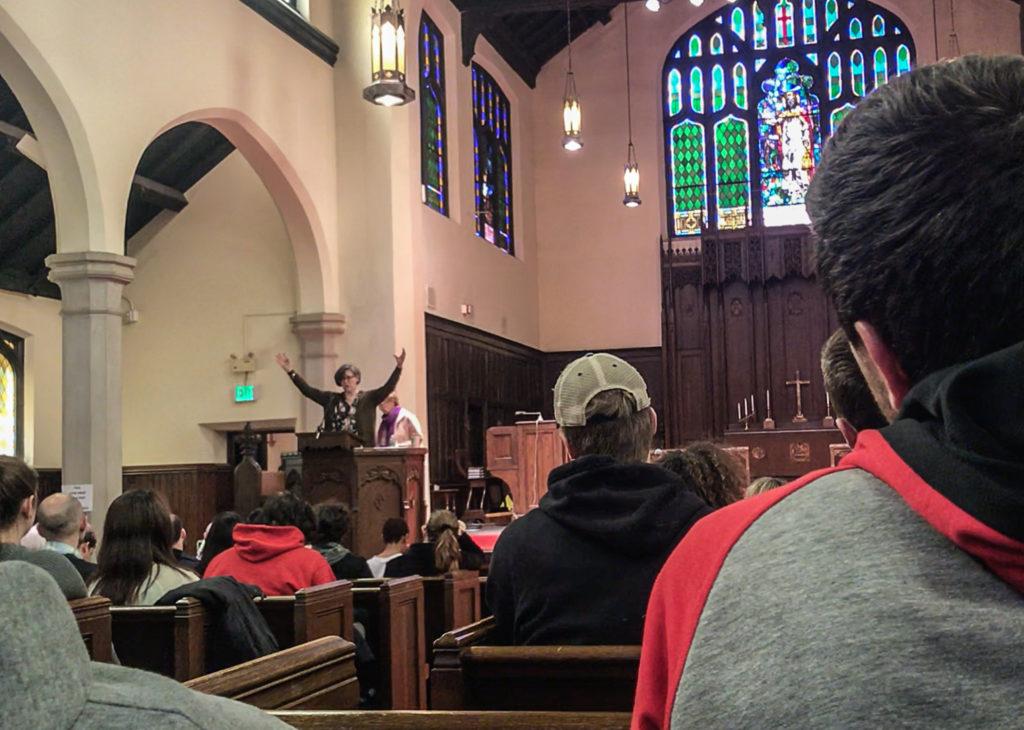

At a town-hall information session for all students on March 11, I remember then-Dean Anne Harris explaining the basics of COVID-19 transmission, how the disease could spread so quickly and easily. Standing at the pulpit of Herrick Chapel, she raised her arms above her head and brought them down in a circle, like a ballet dancer moving through a porte de bras. It was an unexpected and powerful choreography, her hands tracing the deadly vectors of disease that were already moving around the globe.

“We were all in that room because I and others had really started to realize how global Grinnell is, and what it would look like for students to go away for spring break and come. And we knew, we knew, we couldn’t handle the return,” now-President Harris recalls of that day. “It was the most impactful and embodied way that we are a global community. When we leave and come back, the whole world is moving with us.”

Puravi had just applied for what she described as her “dream” internship that March. She was waiting to hear back about whether she had been accepted, which would mean living in the U.S. for the summer. She could stay in Grinnell, hoping to wait out the pandemic for a few months. Or she could leave, not knowing if she would be allowed to come back to the country.

That week, Puravi chose to stay.

A year later, she sits talking to me over Zoom from her room on-campus in Clark Hall, where she’s lived since the shift to remote learning. Puravi has only seen her family once in the past year. I ask her if she had any feeling at that moment in March that she might still be in Iowa a year later.

“I had no idea,” she says. “We all had this impression that it would only last until June.” I remember having that idea as well, as if COVID-19 too would abide by the academic calendar.

**

In another universe, where life did abide by the academic calendar, Alanis Gonzalez and her advisor Dustin Dixon would have gone to Saint’s Rest to get coffee that week. Alanis had just been awarded the prestigious Mellon Mays Fellowship and Dixon had signed an associate professor contract in the classics department. Instead, on March 12, the two were sitting in the Dining Hall, a meeting that seemed more doable, Alanis says, given the circumstances.

Alanis remembers that her phone kept ringing throughout the lunch. Her mom was texting her, worried about whether Alanis had enough cash to pay to store the contents of her dorm room. She didn’t. After Alanis explained the situation, Professor Dixon offered to store her things in the basement of his house, for free.

“He’s a really dedicated advisor,” she says now, reunited with the belongings that Dixon kept for her even as he moved into a new house. Dixon’s offer meant another unconventional meeting the next morning, when he came to her dorm room to help move her things: “I usually see him in his office and he was, like, wearing jeans.”

And while storing Alanis’ boxes at his house was a special case, Dixon had also signed up for a volunteer effort where faculty went around in groups of two or three to students’ dorms to help them pack up and move their stuff.

I still remember waking up at 7 a.m. to a voice that may have been a professor I had freshman year: “Do you need any help packing?” I shouted no thank you and rolled back over in bed. At the time it was irritating; now I feel a great rush of gratitude for whoever was on the other side of that door.

“I was so eager to help,” Dixon explained. “I didn’t know what I could do, what any faculty member could really do to help students move.”

In over 10 years in professional academia, Dixon had never been inside the dorms at any of the universities he taught at. “It was very odd,” he reflects. “I think it’s so important for everybody to have their separate space. Especially at Grinnell, it’s such a tight knit community that we can’t be on top of each other all the time.”

Alanis tells me that handing her professor her possessions made her feel vulnerable. She describes how she had packed up her winter clothes the night before, but the day when she had to move her stuff it snowed. She didn’t have the right shoes or coat and the ground was wet. “I just have this image,” she tells me, “of me and Dr. Dixon trudging around the back of South Campus.”

The absurdity of that scene strikes us both as funny. It fits within my memory of that time as a funhouse mirror of shifting timelines and upended plans.

As I write this right now, I’m wearing a sweatshirt I plucked out of a pile of abandoned clothing on Loose third lounge. It has a drawing of a horse on the back and says “Equus America.” There’s a small purple stain on it that, no matter how many times I wash it, won’t come out. Whoever left the sweatshirt didn’t have room for it in their bags or boxes. The grey crewneck has kept me warm throughout this cold and lonely winter, an artifact of the connections we relied on as we figured out what we did and did not need, concepts that were changing right before our eyes.

**

I think everyone had a moment of realization that their life would change drastically due to the pandemic. At Grinnell, we were lucky in a sense to experience that moment together, in a community where everyone wordlessly understood what had happened, because it happened to them too. And yet it is the very strength of that community, the evidence of our connectivity produced by collective grief, which also made the experience so painful.

Anne Harris tells me about a moment from that week that she can remember clearly to this day. She was standing in her office in Nollen House, about to meet with spring athletes whose seasons would be abruptly canceled. On Park Street, Nollen is nestled amongst the trees, looking out on some of the oldest buildings on campus. The sun was shining and the birds were out. She asked herself, “Why were we causing all this pain?” Then, she looked out the window.

At this point in the interview, Harris tears up.

“I saw five faculty members in full regalia with their robes and I saw seniors with homemade mortar boards and big fluffy scarves, costumes basically. And they were all just parading. Oh, it was the most heartbreaking and also the most joyful thing,” she says to me from that same building, one year later. “This is what community feels like, and you’d only know it when it was being dissolved.”

Walking around campus in March, I took more photos of seniors posing in those mortar boards, girls in their summery graduation dresses despite the March chill. The customary costumes, already imbued with so much significance, took on a new meaning, both joyously and tragically momentous. I think back to Dean Bakopoulos’ email and of his reminder that our hearts can hold vastly different types of grief. So too can we respond to grief in small and large ways.

“I think about Herrick and I think about the focus and the attention and the anger and the loss,” President Harris tells me. “You know that thing of straining forward because you’re trying so hard to understand what’s happening? That’s part of the exhaustion of trauma, because trauma’s so hard to understand, to process information, because trauma hits you all at once.”

I think that the exhaustion, as President Harris put it, of living through a year filled with grief and loss can blind us to the origins of our emotions, making it difficult to remember how we got to where we are today. So often these days I feel like life is just happening to me, that there is no space to maneuver within the confines of an imposed reality. Looking back on the past year, it is tempting to divide my time into “pre-March 10” and “post- March 10,” to forget there was also a week in between.

All of the people I talked to for this piece were surprised by how much they remembered of this time. A couple were moved to tears. Remembering that week is crucial in reconfiguring the tragic, clinical binary of before and after, a negotiation of both grief and celebration when our community came together as it was pulled apart.

I write this essay out of the same impulse that compelled me to photograph Mariyah and the rest of the Dining Hall. The urge to memorialize that moment in between knowledge and understanding; the moment of a change.