Professor Tyler Tillinghast Roberts – previous chair of the Department of Religious Studies, avid reader, scholar, mentor, husband, father, friend – died on June 3, 2021 at the age of 61.

He is survived by his wife, Professor Shuchi Kapila of English, and his children Madeleine, Emma, Will and Shivani.

“He captured the idea of what was human,” said Kapila. “He quietly expanded his universe and didn’t make a big deal out of it.”

Asked about their favorite memories of Roberts, Professors of Religious Studies Yujing Chen, Timothy Dobe and Caleb Elfenbein all had the same reaction: “That’s a lot.”

A Scholar

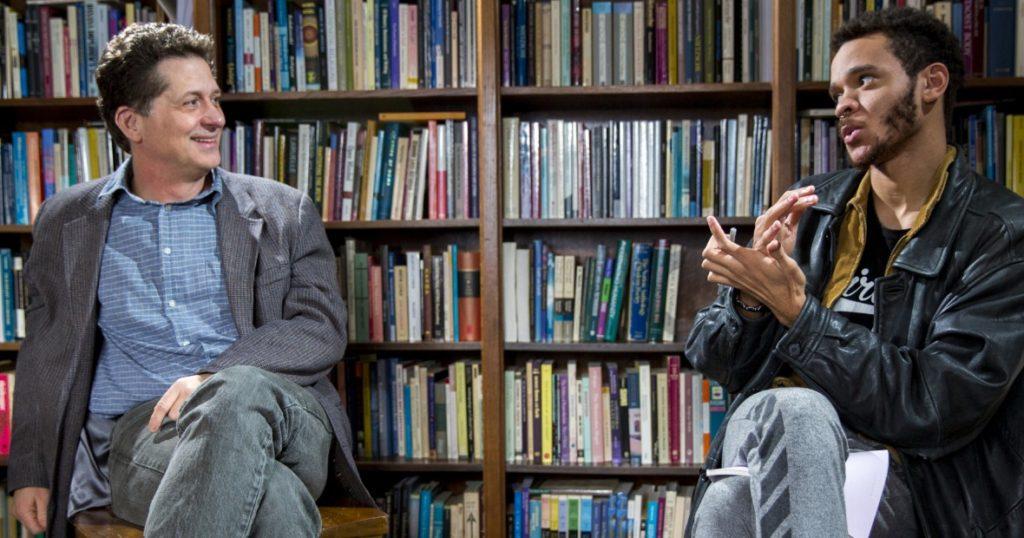

Elfenbein recalls the pose Roberts was most likely to be found in: sitting in the midst of his office, reading with fore and middle fingers pressed against his temples, thumbs on his jaw, with his elbows digging into the desk.

“All of his sweaters had big holes in the elbows,” Elfenbein said.

When someone – a student, professor, staff member, anyone – would walk in to talk to Roberts, he would jolt, startling away from his book.

“It was a moment of welcome,” said Elfenbein. “After being engaged in reading something, he would pop up and look at you.”

“He was always available,” said Chen.

“He is the person whose door is always open, and you know you are going to get specific and supportive advice if you go in,” said Dobe. “You will leave different from when you came in.”

And he was always reading. That was the kind of thinker he was. He would absorb the information around him diligently. As department chair, Roberts would guide faculty towards new ways of thinking. According to Chen, he was the one who gave the department direction.

Roberts’ support was evident in the way he mentored Chen, helping guide her through Grinnell as a new faculty member with his experience.

“After I finished my tutorial syllabus, I asked myself, ‘What kind of suggestions would he give?’” said Chen.

Roberts also offered to help the members of his department with anything they might need. When the derecho hit Grinnell, it cut the phone connection for Chen. And despite the fallen trees and debris, Roberts and his wife, Kapila, went to check if she was okay, knowing Chen had just moved to Grinnell to teach.

He is the person whose door is always open, and you know you are going to get specific and supportive advice if you go in,” said Dobe. “You will leave different from when you came in. -Professor of Religious Studies Timothy Dobe

“He provided mutual support in a small department,” said Chen.

“When I said that I wanted to be the director [for the Center for the Humanities,] he didn’t bat an eye,” said Elfenbein. “Looking back, that meant he was going to spend more time as department chair, and he didn’t raise that as a problem. … He was open to me pursuing things that were fulfilling.”

“He was amazing at recognizing the will of the group,” said Elfenbein. “Accepting the decision and moving on, doing his utmost to make sure that whatever decision we had made was successful … that’s rare.”

Elfenbein and Dobe remember how Roberts’ thinking broadened out to include new horizons over the course of his time at Grinnell. With his first book, he was specifically focused on Nietzsche, affirmation and religion. In his second, he asked where the field of religious studies was going in the future. And with his third big project – what he was reading on the most in the months leading up to his passing – he asked what we do with the humanities as an area of scholarship.

“He was asking, ‘What is this all about? What do we do?’” said Dobe, “If we don’t reshape our commitments in the way we live, based on what we study, then we’re missing out.”

A Mentor

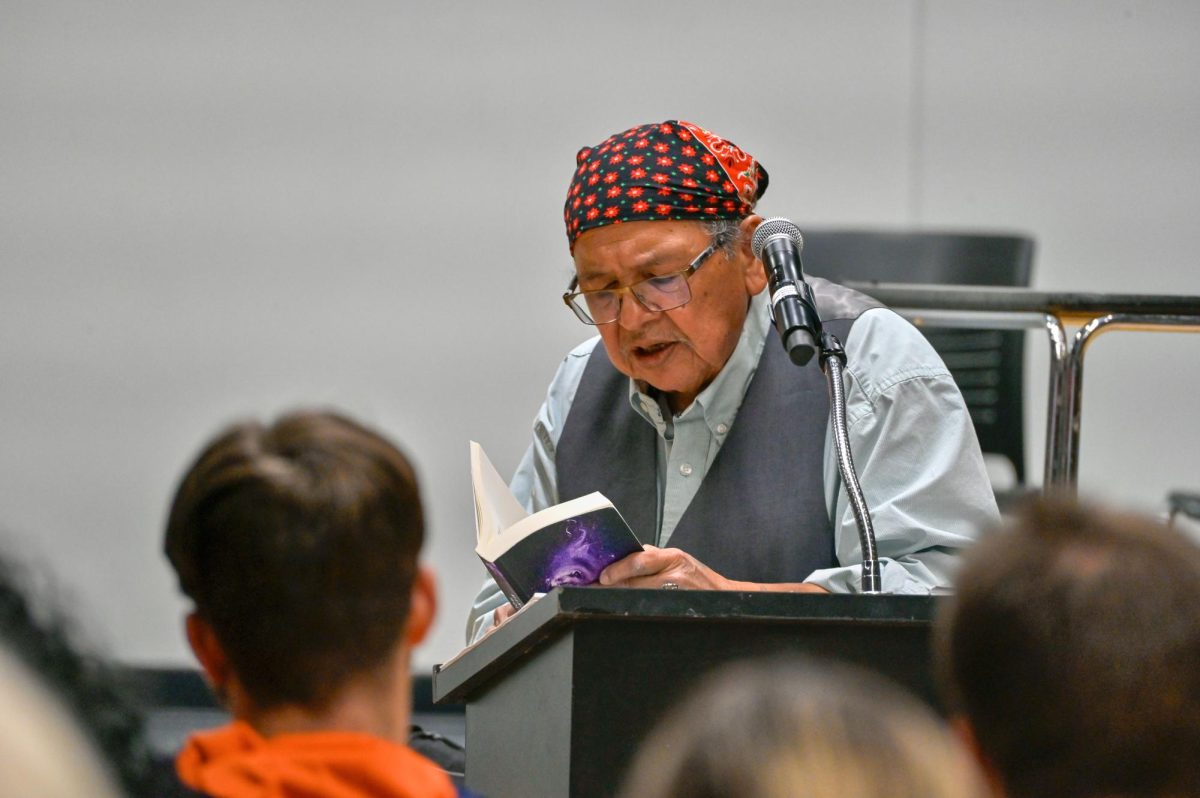

When Roberts was in the classroom, his mind and body were never stationary. Rolling back and forth on his heels, leaning on the back of a chair, scribbling on the board, he would not stop moving. And at the beginning of each class, still fidgeting, he would begin to tell a story that related to the lesson he was about to teach.

“Usually, it was a story that came from his own life. At that time, his children were infants,” said Jolyon Thomas `01, now an associate professor of religious studies at the University of Pennsylvania. “And before you knew it, he would turn that into a lesson about the readings that we’ve had for that day. It was like magic every time he did it.”

Jenny Samuels `16 took Roberts’ class on religion in U.S. public life. She has just graduated from Harvard Law School, and is now clerking for a judge.

“I kept all the books from that class, which I know I didn’t do for any other class,” said Samuels. “I still revisit the cases we studied.”

Samuels cites Roberts as a dramatic force on her worldview, who changed the way she approached the law. According to Samuels, she has not been able to find his unique viewpoint ever since.

“I haven’t seen any other scholars even come close to his depth of understanding and his vision for what the meaning of religious freedom is,” she said.

Now, standing in Roberts’ footsteps, Thomas reflects on his own role as a professor. “I know that my debt to him is something that I can never really repay. Especially – and I should stress this – because I was a terrible student,” said Thomas, “But now, I have the opportunity to pay it forward.”

A Friend

Although not everyone was lucky enough to have witnessed it, Professor Johanna Meehan, philosophy, recalled Roberts’ wickedly playful side, a remnant of his days in New England. Dobe described him as a “partier,” “mischief maker” and “quite a rebel.”

Meehan’s friendship with Roberts stemmed from their shared humor and wit, she said.

I haven’t seen any other scholars even come close to his depth of understanding and his vision for what the meaning of religious freedom is. -Jenny Samuels `16

“When we’re at meetings,” said Meehan, “we catch each other’s eyes across the room … and he would smirk. I miss that smirk. The one that said, ‘we both know this is ridiculous, but neither of us can say it.’”

At home, Kapila said Roberts loved to laugh at life. He would play scenes from Monty Python’s “Life of Brian” over and over again with a kind of glee. For their first date together, Roberts took Kapila to see “Knocked Up,” a “boys’ comedy,” she said.

“I both liked to watch it, and watch him laughing,” said Kapila.

According to Meehan, Roberts also spent a fair amount of his free time thinking and talking about music.

“He was the only person who thought Bob Dylan deserved the Nobel Prize for Literature,” said Meehan.

While cleaning out Professor Tyler Roberts’ office, Professor Caleb Elfenbein found Roberts’ answers to an assignment he had given to his tutorial. Roberts had asked his class to analyze their favorite song. According to multiple friends of his, Roberts’ own favorite song was “I Want to Hold Your Hand” by The Beatles.

“It was very Tyler,” said Elfenbein. “On the one hand, it showed that he understood the craft of music, how people put melodies together and the rhythm of a song. But then, he really thought about meaning.”

Roberts poked much fun at his friends, but he would let himself be poked in return. Once, Elfenbein and Roberts were discussing something open on Roberts’ computer, when Elfenbein noticed a tab open in the browser.

“So, when you come in here early, and you say you’re reading,” teased Elfenbein, “You’re really reading about the Red Sox.”

“You have to be quirky to like the Red Sox,” said Meehan.

Instead of co-workers, Roberts had lifelong friends. People he supported, teased and cared for like family.

“In my experience,” said Elfenbein, “male friendship in middle age and after is pretty hard. Culturally, having intimate male friendships … it’s not that common. And to have that with someone you respect. I miss that a lot.”

“He was my great love and best friend, an amazing partner, and the kindest person I knew,” said Kapila.

“I think he wanted to see me grow in whatever way was meaningful for me,” said Elfenbein.

A Family

With both Dobe and Roberts being from New England, they were able to bond over creating a new family life for themselves, transplanted to the prairie. Dobe marveled over the way Roberts modeled positive energy for his family even when he ended up in the middle of nowhere, and became closer friends because of it.

In my experience, male friendship in middle age and after is pretty hard. Culturally, having intimate male friendships … it’s not that common. And to have that with someone you respect. I miss that a lot. – Professor of Religious Studies Caleb Elfenbein

Roberts loved being at home, said Kapila, and created a peaceful place for them both to enjoy living together as a family. It was a shared space where they could invite friends over for dinner to have a great time, and especially for their children during the holidays, where they could have a homecoming tradition to some “pretty good food.”

“I credit Tyler with the ability to give everyone a place in the house,” said Kapila.

And outside of the home, with his children, Roberts would still find a way to create that family bond. Meehan’s and Roberts’ children attended the same Grinnell public school. For their “holiday” concert, each year, Meehan would denounce the posited neutrality of it, as all of the songs played were Christmas songs, not generic holiday songs. But Roberts defended the presence of religious songs in the public sphere – though he agreed with Meehan that they should be honest with their labeling. And yet, Meehan said, he would laugh at her agitation every year.

“And you start laughing, because it’s so predictable,” said Meehan. “I know what you’re going to say, you know what I’m going to say. But still, there is space for us to say it.”

Roberts had a way of bringing everyone around him together, according to Kapila. He never made her worry about the nuances of an intercultural relationship. Not only did their wedding bring their two families and cultures together, but also enveloped their friends into their lives. Meehan’s backyard served as the wedding venue, while Dobe was the officiator.

And near the end of his life, Roberts had just begun learning to play the guitar with his son, the difficulty of which challenged and invigorated him, according to Dobe. Elfenbein had eventually convinced Roberts to strum along while Elfenbein played the drums. Together, they made something “identifiably music,” said Elfenbein.

“Roberts is the guy strumming in an irreverent spirit to Lou Reed,” said Dobe.

And he was also a professor, a mentor and a friend. A Beatles lover, a father, a thinker. All identifiably Roberts, and all at once.

“I don’t know what part to remember first,” Chen said. “Because for us, it’s everything.”

Johanna meehan • Nov 16, 2021 at 8:24 am

I think you did a beautiful job.

Mira Livia Berkson • Nov 15, 2021 at 4:37 pm

Prof. Roberts’ (am I allowed to call him Tyler yet??? Idk) passing hit hard this past summer and I am grateful to still be able to learn from him and those close to him, and to see the space of his life being held with care and truth. Incredible reporting as always, Lucia.