2022 Iowa College Media Association award winner, Second Place – Best Print/Online Review

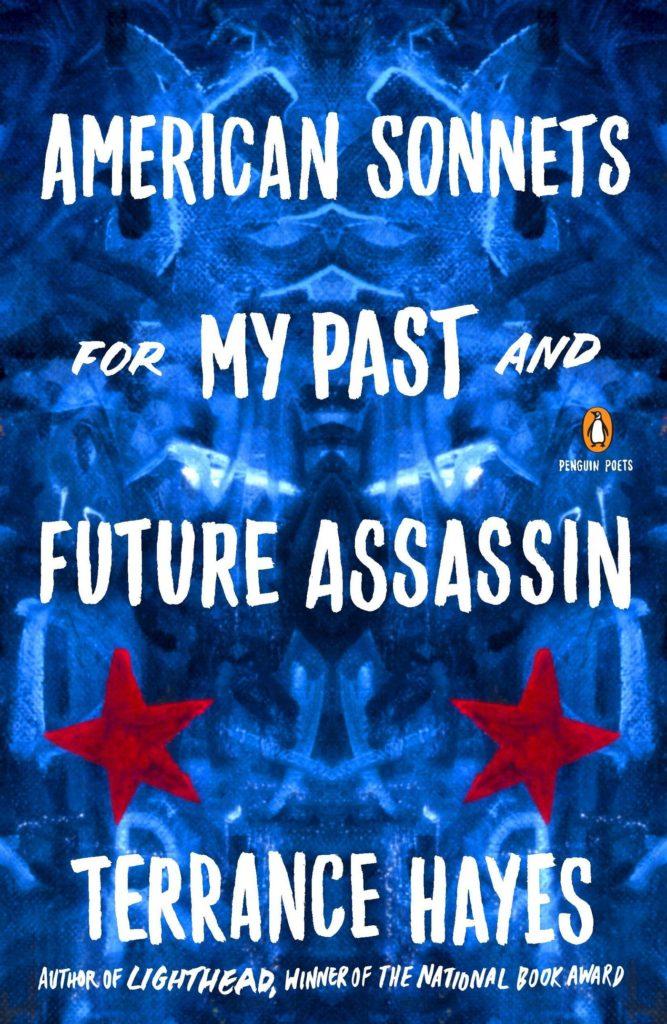

“Why are you bugging me you stank minuscule husk / Of musk, muster & deliberation crawling over reasons / And possession I have & have not touched? / Should I fail in my insecticide, I pray for a black boy / Who lifts you to the flame with bedeviled tweezers / Until mercy rises & disappears,” writes author Terrence Hayes in the fourth sonnet in his 2018 poetry collection “American Sonnets for my Past and Future Assassin.”

Whether this poem addresses a literal or metaphorical stinkbug, Hayes leaves the reader to decide. But what’s not for the reader to question is the sonnet’s brilliance, innovation and elocution. These traits are not just present in the above sonnet but exist throughout Hayes’ entire collection.

Hayes wrote the seventy poems in “American Sonnets for my Past and Future Assassin” between late 2016 and 2018. It was a finalist for the National Book Award for Poetry and shortlisted for the T.S. Eliot Prize, two of the most prestigious literary awards for poetry.

These accolades aren’t surprising. There is no form more tailored to Hayes’ verbal onslaughts than the sonnet. Hayes varies the meter of each poem with intentionality and care. The fourteen lines of a standard sonnet capture Hayes’ passion, love and rage without overwhelming or exhausting the reader.

Some reviews of “American Sonnets” describe the book as an exploration of masculinity, politics and racial justice. While these themes are present — and explored poignantly — this characterization reduces Hayes’ work and misleads potential readers.

Like most poets, Hayes allows for some subjectivity in what lessons the reader draws from the book. Hayes leaves the identity of this assassin, whether metaphorical or literal, past or future, open to the interpretation of the reader. Each poem itself has the same title: “American Sonnets for my Past and Future Assassin.” This nomenclature technique draws a common thread line throughout each poem, even if they appear dissimilar at first.

Hayes does not replay common tropes of political division and frustration. Rather, what he does so brilliantly is he synthesizes the complexities and contradictions of what it means to be a person in the modern United States. His unbridled, rhythmic diction in poems like the sonnet beginning with, “The umpteenth thump on the rump of a badunkadunk” enigmatically articulates the confusing yet tremendous anger so many U.S. citizens feel in a state as perplexing as ours.

Don’t misread me: when Hayes finds a person, situation or trend appalling, he calls it out by name. But for each sonnet that tears into a political phenomenon, like in the poem that begins, “Goddamn, so this is what it means to have a leader,” there is another sonnet exploring the painful universalities of the human condition. In the poem beginning “Sometimes my father almost sees looking,” Hayes writes about the distinct ways sons view their fathers versus the ways fathers view their sons. He explores this dichotomy with references to death, memory and the progression of time. Past, present and future converse with each other, creating a universal tale of familial love and loss.

After I finished “American Sonnets,” I was left with magnified empathy and a sturdier conviction for justice than before I picked up the book. I sought out more poetry, academic research and novels relating to the themes Hayes discussed. As readers, we navigate the books we read with a paradoxical cathexis; to invest ourselves in a narrative is to intentionally knot our heartstrings so tightly that we burst and tear ourselves apart upon the last page.

Creative narratives, even nonfiction, that are too belabored or too painful can often blind us to injustice because we can only emotionally process the stories with a presumption that they’re hyperbolic. At least, this happens to me, ridding me the opportunity to integrate the lessons from the narrative into my view of the world. This was not the case with “American Sonnets for my Past and Future Assassin,” because Hayes circumvents this by keeping us tied to a story bound together by familiar themes and a recurrent form. This collection pushes us to dig deeper after we set our book down. As all good books should.