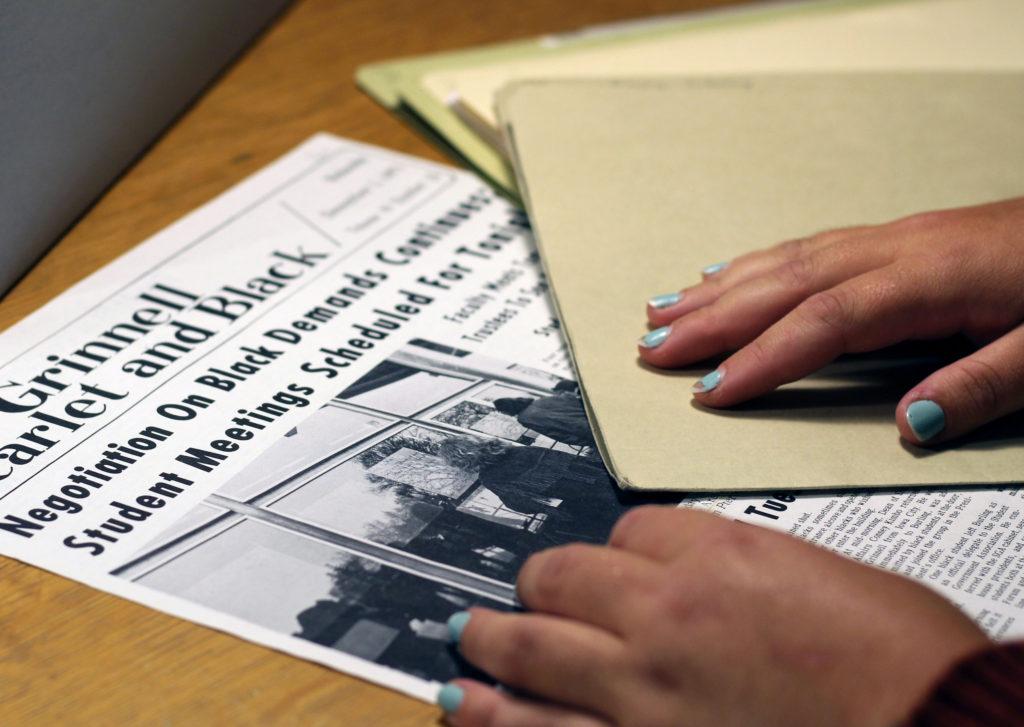

On Nov. 29, 1971, Concerned Black Students (CBS) chained the doors of Burling Library shut.

In an effort to call attention to “the racist atmosphere which prevails” at Grinnell, CBS staged a sit-in library takeover protest. In order to negotiate the terms of what they called “The Black Manifesto,” CBS protestors staged their takeover where, at the time, the College’s administrative offices were located, according to Library Archivist Chris Jones.

Out of the 10 demands in the Manifesto, only a few have been met today.

CBS requested more involvement and input from Black students on committees, specifically the introduction of a Black Admissions Council. They also demanded the adjustment of dining accommodations to either diversify the food options or allow students to go “off board” and not participate in a dining plan, which the College still does not offer to on-campus students.

Another key need was more classes and visibility to Black history and culture at the College, such as the establishment of the Black studies library, the introduction of Black studies classes and the inclusion of more Black students on campus in general.

As of 2021 — 50 years in the future — these demands have been at least partially met, or met and then later removed, such as the Black Admissions Board, which was disbanded following concern about separating the admissions process by race, or the Black studies major.

For those 50 years, Grinnell has seen cyclical, “redundant” conversations around racism, according to professor of anthropology and American studies Katya Gibel Mevorach, a lack of lasting change she calls “institutional amnesia.”

Gibel Mevorach came to Grinnell in 1996 to head the Africana studies concentration — an idea that had arisen from the Manifesto, which called for the creation of a Black studies major in 1971. At the beginning, Mevorach said she had positive hopes for the expansion of the Africana studies program.

Instead, the program ended in 2005 and shifted to the broader American studies concentration. According to Gibel Mevorach, one of the reasons for the cessation of Africana studies was a lack of interest from students in taking the classes and declaring the concentration.

The Black studies major was just one of the demands that CBS brought with them in November of 1971. Many of the conditions are still the subject of conversations being had on campus today, which Gibel Mevorach says is a familiar cycle at Grinnell.

According to Gibel Mevorach, student protest actions typically happen in the spring, and then, when students leave for the summer, or to graduate, that momentum is lost, and Grinnellians go back to the beginning to “reinvent the wheel.”

“So, by not remembering what happened, one can always start at the beginning and pretend we’re just beginning now,” Gibel Mevorach said. “And I don’t believe in that. I believe there needs to be accountability and responsibility.”

The effects of institutional amnesia, according to Gibel Mevorach, can be seen in the way that Grinnell does not recruit or retain many Black faculty and students.

According to her, Black faculty that leave don’t always explain the real reasons they left, such as “feel[ing] a hostile environment.” Additionally, the conversations and efforts around diversifying recruitment are often repetitive and ineffective.

“There’s accountability that is still required, and it’s not simply to say ‘Oh, we need to do a better job of recruiting Black students,’” said Gibel Mevorach. “I don’t think that’s proven itself, because it’s the same conversation, year after year after year.”

When the Black Manifesto was written in 1971, CBS demanded that there be more than 200 Black students at Grinnell College. In 2019, only 4.5 percent of students identified as Black or African American, while there were 1,733 students enrolled. In order for there to be more than 200 Black students on campus, that percentage would have to have been closer to 11.5 percent.

One effort taken to improve overall student diversity was the Posse program, a scholarship program that helps disadvantaged students find colleges that fit them. Posse scholars are selected in small groups based on geographic area, allowing these students to have a built-in community within their college, according to the Posse Foundation’s website.

Grinnell College chose to end its relationship with the Posse Foundation in 2016, with then-President Raynard Kington citing interest “in a more comprehensive approach to achieving our goals for diversity and overall student success.”

CBS spokesperson Raven McClendon `22, who has participated in on-campus antiracist activism and discussion during their time at Grinnell, remembers their Posse scholarship interview.

“The day after my Posse interview, I told my guidance counselor that I mentioned my trip to Grinnell, and they were like, ‘You shouldn’t’ve did that,’” McClendon said.

According to McClendon, the existence of the Posse program at Grinnell was vital for increasing diversity, but also for making Black students feel safe and welcome, which they pointed out as a distinct problem on Grinnell’s campus — a sentiment that echoes the reasons that CBS protested in 1971. McClendon mentioned that they had had several adverse experiences on campus that were a result of racism at Grinnell.

“There are many things that I’ve experienced that there was no reason for me to experience,” said McClendon. “I simply want Grinnell to be a space … where [Black students] are proud to graduate from.”

Another issue McClendon commented on was the possibility of a lower retention rate for Black students as a result of racism on campus, which they said has negatively affected their college experience.

“Me and my friends were talking about how … [there’s a] joke that each year, a Black woman goes crazy,” said McClendon. “And that semester, I guess it was me. I felt it. I felt it coming on.”

McClendon says that, after moving back home due to the COVID-19 pandemic, they saw a Black psychiatrist and therapist, who they feel were better equipped to understand their problems than the therapist they had seen in the town of Grinnell.

They said that they feel Black students, faculty and staff are having to repeat the same points about inclusion and antiracism, which they say shouldn’t have to happen. In August of 2020, McClendon and Errol Blackstone `20 published a list of 14 demands following an incident in which a professor used the n-word in class. Since then, McClendon has published a response to a statement from President Anne Harris concerning antiracist work on campus.

When asked their opinion on the fact that many of the 1971 demands have yet to be met, McClendon said that they think it means that Black students are not being listened to.

“You have to engage in the conversation that Black people want to have,” said McClendon. “You can’t abandon this Black Manifesto for 50 fucking years and say, ‘We’re gonna have diversity here, and diversity there,’ … When someone is having to repeat themselves, it means you’re not listening.”

Editor’s note: This article has been updated to reflect McClendon’s position as a CBS spokesperson. A previous version of this article referred to them as a cabinet member and not a spokesperson. The S&B regrets this error. Updated Oct. 4, 2021, 9:05 a.m.

Raven McClendon • Oct 4, 2021 at 2:51 am

If I could have read this beforehand, I would not have approved this article or my quotes/experiences that were used in it. I was interviewed for at least 20 minutes, and I cannot believe this is the article that was the result of my (wasted) time. I am not just a CBS cabinet member. I am one of the two CBS Spokespeople. This article doesn’t tell me much about the original Black Manifesto or the work that the current CBS cabinet has done to revamp it. Also, if y’all can reach out to me for quotes, y’all can damn sure tell me when MY words will be published. MY words have been published for 16 days, yet this my first time reading them. I am displeased.