As vaccines become readily available and COVID-19 cases fall across the United States, a return to pre-pandemic life is approaching for many domestic Grinnell College students. But many international students face a different, more brutal reality: exploding COVID-19 surges in their home countries, strict visa regulations and insufficient vaccine access for them and their families.

“Things here feel like we’re sort of back to normal. For most of our international students, it doesn’t feel that way,” said Karen Edwards, director of International Student Affairs at the College. “For them, it’s been navigating ever-changing visa regulations, border issues, all that, on top of their worries for family and friends and people they love.”

Ahon Gooptu `21 is from the city of Kolkata in the state of West Bengal, India, and has been living off-campus in Grinnell for the 2020-21 academic year. India has seen a staggering rise of COVID-19 cases since the beginning of April, shattering global-records with 412,431 cases on May 5.

“I haven’t been able to focus on any work,” he said. “It’s such a distressing situation because we get heartbreaking and devastating news pretty much every other day about someone that we know of. Either they’re sick, or they’re dying.”

Despite the magnitude of India’s reported case counts, many epidemiologists believe that this number is drastically underestimated. COVID-19 case rates in India could be up to 10 times higher than reported cases due to lack of testing.

More than 230,168 Indians have died since the pandemic began. Over the past two weeks, death rates have increased by 102 percent, and yet deaths are also massively undercounted.

“India is burning. Bengal is burning,” said Gooptu.

The spike in cases comes after India averaged less than 20,000 cases a day just a few weeks earlier in March.

Writam Pal `23 currently lives in Kolkata. He said that though the reported numbers were very low in March, he thinks that the low numbers were misleading due to extremely inadequate reporting at the time.

“I wouldn’t really say in March the cases were low, it’s that they were undocumented. And as time progressed, it just became more documented and structured. … You can’t really be sure about the total cases in the country.”

On May 4, Pal tested positive for COVID-19 with mild symptoms, and he is quarantined in his house with his father. His initial plan was to wait to get vaccinated until he reached the United States. That changed when he tested positive.

It’s such a distressing situation because we get heartbreaking and devastating news pretty much every other day about someone that we know of. -Ahon Gooptu ’21

Vaccination appointments opened up to all West Bengal resident age 18 and older on May 5, and Pal said he believes he will be able to get a vaccine appointment before the fall.

Gooptu received both Pfizer doses in Grinnell, but he is concerned about his parents in India who may be unable to get an appointment for their second dose of the Covishield vaccine to due scarce supply. The vaccine is a locally manufactured version of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine produced by the Serum Institute of India (SII). Covishield is the most widely used vaccine in India, and as cases rise, so does the demand for the shot.

As of May 6, the SII is only producing 60 to 70 million doses per month, nowhere near the estimated 250 million doses India needs per month to fill vaccine drives to full capacity. This shortage of doses may last through July.

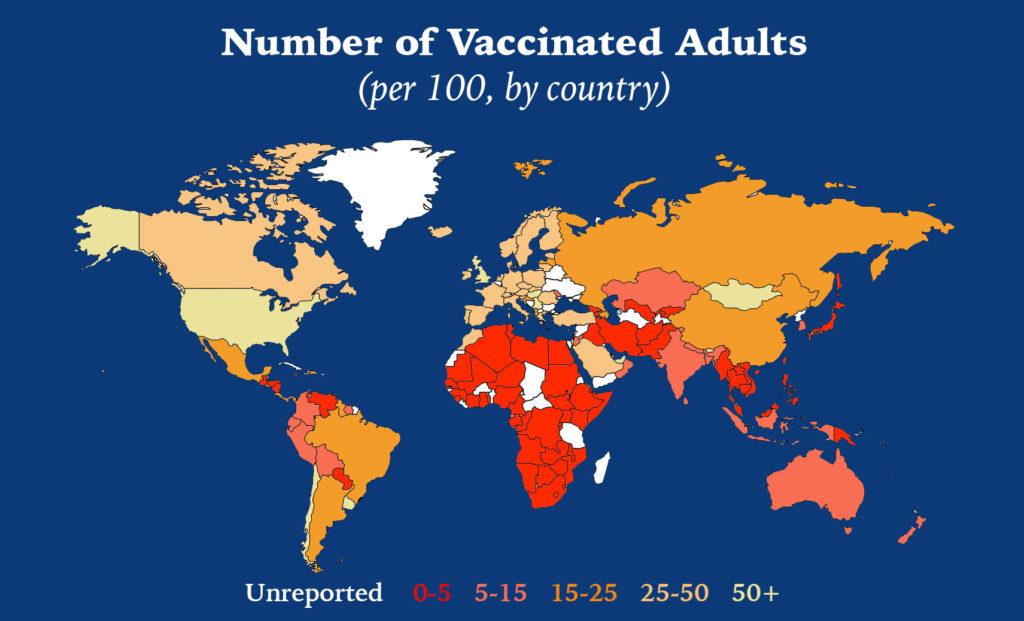

Only 2.1 percent of India’s 1.4 billion population have been fully vaccinated. An additional 9.2 percent of Indians have received one of two doses.

“It’s so distressing to me that people are taking a voluntary choice not to get it [in the United States], where people are like fighting to get it in India,” said Gooptu.

Pal said that vaccine hesitancy is a problem not just in the US but in India as well. He said that some of the vaccine resistance is a result of distrust for the current Hindu-led government, the Bharatiya Janata Party, which is causing many Indians, especially those in majority Muslim localities, to be doubtful of the vaccine.

Gooptu added that, in some ways, politically driven vaccine hesitancy in the United States mirrors politically-driven vaccine resistance in India.

“[Political parties] were using the pandemic and the virus as a means to an end for the political campaigns. We’ve seen that in the US as well. This was just being repeated in its own form in India,” said Gooptu.

Carolina Klauck Novaes `23 left for Grinnell the week of March 14, right as her home state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, reached its peak in March. In Rio Grande do Sul, one in every 11 people have tested positive for COVID-19.

“All hospitals were full. People were dying in line for an ICU bed,” she said. “It was so full. Everything was crazy.”

Brazil is third in the world for COVID-19 cases behind India and the United States. This past week, there have been an average of 59,332 cases per day.

6.7 percent of Brazilians are fully vaccinated, with an additional 7.3 percent of Brazilians having received their first dose.

Demand for vaccinations far outstrips the supply. Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro declined shipments of over 100 million vaccines for Brazil in 2020 and has repeatedly downplayed the efficacy of vaccines against COVID-19 transmission. Additionally, the Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency declined approval on April 26 for the Russian COVID-19 vaccine Sputnik V, citing safety concerns.

The difference between vaccine availability in Grinnell and in Brazil was shocking, said Klauck Novaes.

“Literally the minute I got here, when I entered the city of Grinnell, I got an email like, ‘Yeah, schedule your vaccine,’ and I was like, oh God.”

Things here feel like we’re sort of back to normal. For most of our international students, it doesn’t feel that way. -Karen Edwards, Director of International Student Affairs

Looking ahead to the 2021-22 academic year, Edwards said that the primary concern of the College’s International Affairs office is that there may be students who are unable to travel to Grinnell next year due to consulate closures and visa backlogs in countries like India and Brazil.

Approximately 52 international students who are current first-year students have not yet been able to secure an F-1 visa to come to Grinnell in the fall of 2021. There are also about 90 international students in the class of 2025 who will need to acquire F-1 visas by August.

Though she said that in prior years the office has had mild worries about students being unable to acquire visas, the issue this year has been severely exacerbated.

“It’s absolutely specific to the pandemic,” said Edwards. “Our first and primary goal is to do everything we can to help students be on the ground ready to give these applications and get appointments as soon as they become available.”

CYNTHIA L BAKER • May 8, 2021 at 2:15 pm

Great article. The statistics noted are stunning, and sobering. Also, the world map is impactful. I stared at it for several minutes, trying to absorb the vast disparities. It’s heartbreaking, really.

Jamie Thompson • May 8, 2021 at 12:52 pm

I enjoyed reading this! Great job Nina!