What does it mean to be Asian American? Is there a pan-Asian American identity? Will we find answers to how we can reconcile being a part of a diaspora to our role in society today? In other words: if it looks like a duck, walks like a duck and quacks like a duck, is it Asian American?

As a Chinese American struggling with these questions myself, I talked to individuals from Grinnell College about how they wrestle with their racial identity in this present moment.

There is no single story that can explain what it’s like to be held up as a model minority and yet still be discriminated against. We each come with our own unique voices, some of which are collected here, a time capsule of how individuals view their identities. In the wake of the Atlanta shootings, horrific violence can reduce us to a narrative of victimhood, erasing the nuanced differences between us and hiding those identities, resulting in a shallow version of solidarity held together by a racial label.

(And I have to correct a mistake on my part – in this article, you will read interviews from, specifically, East Asian Americans. Because Asian Americans are not a monolith.)

We can stand in solidarity with the Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) community while recognizing our different lived experiences. Which gets at the main question plaguing us today: what does that solidarity even look like anyway?

Interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

Lizzy Zerez ’22

Elizabeth (Lizzy) Zerez `22 is an English major who grew up in Hawaii in a community with other mixed Asian individuals. She is half Chinese and half Middle Eastern, which, according to Zerez, leads to much confusion over her last name.

The S&B: Where did you grow up? How does it compare to Grinnell?

Zerez: Being from Hawaii, I rarely felt like I stood out as a minority. When I came to Grinnell, I was donning the Asian American label for the first time. And it’s something I’m still trying to figure out to this day. I’ve been myself my whole life, but I never became a person of color, so to speak, until I came to Grinnell.

I remember this moment in my freshman year, when I was in my dorm room, as one is. I looked in the mirror and, for the first time, I saw something. I saw something besides the face that I always saw in the morning. And I got it. I don’t really look like everyone else. Which is a weird thing to say because Grinnell is very quote unquote “diverse,” but still, the majority of students are white. I think that’s when I realized the Asian American label was coming on to me.

[In Hawaii, conversation about race] felt very comfortable and normal, because I’d be talking to other mixed Chinese or Chinese people. I sometimes feel like, in Grinnell, part of these conversations is me explaining myself and hoping that people take my word for it. I definitely feel a bit out of place [at Grinnell,] even if no one said anything overtly racist. I felt like there was no common ground culturally anymore. I felt a little bit like I was code switching all the time.

What does an Asian American identity mean to you?

I almost feel like a newbie at being Asian American. It was a privilege to be raised in an environment where I was largely in the neutral group. In some ways, I feel like I don’t quite belong as an Asian, like a mainland Asian American.

Lately, I’m coming to a place of more pride. I wonder if that comes from, “Well, if I don’t have this really strong pride, will I get walked all over?” It’s something I cling onto, especially at Grinnell. When I was removed from the environment being surrounded by people like me, I clung to rediscovering.

What do you think about the AAPI label?

Largely speaking, the Asian experience is so different from the Pacific Islander experience. To me, Pacific Islanders in Hawaii have faced the threat of colonialism and mainland Asians haven’t necessarily had to experience that in America. It is not their native land.

I do know people who appreciate that label, and who do feel like it’s applicable to them. There’s a solidarity to be found when you create a unifying label like that. Even just “Asian American” can mean so many different things, which is why I was hesitant to say, “Oh, the Asian experience is so different from the Pacific Islander experience.” Filipinos also experienced colonialism, and that history still affects Filipino Americans.

There are also hierarchies within the Asian American community. For first generation immigrant kids, if you still speak the language of your mother country, that puts you above those who don’t speak it. If you’re full race, that puts you above the mixed kids. It comes from a place of wanting to preserve culture, to hold onto it, even if you’re away from the home country. At the same time, assimilation is sometimes a defense mechanism, and you have to do it to survive.

What does culture mean to you?

When I think of culture, I think about food, holidays, and also the values you were raised with, how you were taught to act and think. And definitely language.

My grandma and her siblings are the last generation of my family to speak a Cantonese dialect. I don’t think she saw the point in passing it down, because now, everyone around her is an English speaker. I think they knew it would be easier to focus just on English. For me, I have been learning Mandarin for a while since I was a kid, which is kind of funny because my family doesn’t speak Mandarin. It’s much harder to find a class to take Cantonese lessons.

I also didn’t grow up speaking Arabic. There are not a lot of Middle Eastern people in Hawaii, and I asked my dad once, “Did you ever think about speaking to me in Arabic when I was young?” And he said he didn’t want to impose it on me. It’s a very interesting way to put it, because where we live, English is the default. And anything else is seen as secondary.

Professor Sharon Quinsaat

Sharon Quinsaat is an assistant professor in sociology and a part of the faculty with the peace and conflict studies program, as well as the American studies concentration. She was an international student from the Philippines and came to the U.S. as a Fulbright Scholar to study before her master’s degree. She developed her interest in migration by learning about her mother’s experience as a migrant, thus leading her to Grinnell.

The S&B: What was your perspective as an international student coming to the States for the first time?

Quinsaat: I did a lot of thinking about the ways in which I could identify with Filipino Americans who were born in the U.S.. In my perspective, they were just Americans, in ways of thought and practices. And I’m not.

The way I understand race is that I’m coming from a society where I’m part of the so-called dominant group in terms of ethnicity. There’s a process of racialization. The divide is mostly among Christians and Muslims in the Philippines, and then you have the indigenous population, but there are also ethnic divisions among people in the Philippines. I’m part of the more dominant ethno-linguistic group in terms of numbers as well as politically and economically. But, when I came to the U.S., I immediately became this racialized individual, and I was categorized as Asian. For example, if you’re Filipino, it becomes less and less visible for other Americans, and they will just code you as Asian. I had to resocialize to get to that kind of racial description. That’s a very U.S.-centric approach to knowledge. There are things that you can’t learn by reading about it. You need to experience it.

How did immigrants handle becoming racialized?

For a lot of Asian immigrants, it’s stratified by class. The way they understand their own experience is also mediated by their experience within the labor structure of American society. So, the belief, for instance, among many of those who [have high class mobility] already, are Asians who work in Silicon Valley. Some of them may think that this idea of American Dream was right and believe there is a middle class of high skilled workers. There’s a reinforcement of that sort of thinking that there is mobility through the labor that they put in the tech sector.

If there is so much stratification, is there a meaning to the label “Asian American?”

The panethnicity was constructed specifically in the 60s during this time of social unrest, and a lot of organizing by racial groups for the civil rights movement. They constructed this notion of panethnicity as something that is not only imposed from above, as something imposed by the state, but also constructed from below, as a means of claiming resources inside and outside the community.

What makes [the label Asian American] important is that [Asian American activists] reclaimed it. They reclaimed that external, socially imposed category, and made it a political identity. We’re divided based on our history of conflict within the regions. But our history of common oppression here will unite us. The ways in which the state, and even the dominant group, especially look at us as “forever foreign.” It’s a way for us, too, to build a culture of resistance.

If “Asian American” has been used as a political identity, what does this mean for the commodification of culture? What is “Asian American” culture anyway?

What does that even mean, right? Did we have a meeting, and agree that, “This is an Asian American movie,” or something? People tend to think we all originated from some kind of culture that engages with dragons or ninjas. You are reduced to that. You are commodified. Because people think that there is an essence, “Asian” in a bottle. And then you sell it. That functions with consumer-capitalist culture.

But culture is not like that, in that sense that culture is tied to identities and communities.

Asians here in the United States, and in the diaspora, are influenced by what’s going on in our homelands, or our ancestors’ homelands. The geopolitical relations among various states impact us broadly. … There’s tension and contradictions, and when you’re doing anti-racist work, you have to navigate these cracks and fissures. You have to achieve a balance between being critical of the Chinese state or the Chinese government, without adding to the already anti-China rhetoric of the dominant white majority that is controlling the U.S. state.

How does this affect how information is passed down throughout the generations?

Many groups who came in as refugees – Vietnamese, Cambodians and Laotians, for instance – have been brutalized by war. They didn’t have a lot of cultural capital when they came to the U.S.. But they also can’t talk about the war and haven’t passed down these narratives of the war to their children. There’s no healing on the part of many Cambodian Americans. The thing about identity construction is that it is relational, it’s dynamic, it’s interactive. If you’re unable to talk to your parents about this, then how do you learn about who you are?

And there are those groups whose parents came here with a lot of cultural capital. They are educated and came in as doctors. They have PhDs. They’re able to transmit a lot of these narratives to their children in ways that help them understand who they are and also how to adapt to American society. That’s why we cannot speak of an “Asian American experience”, because there’s no single Asian American experience.

What does standing in solidarity with the AAPI community look like to you?

So many conversations, especially after the shooting in Atlanta, is to center our solidarity on the most vulnerable in our community, which are those which are precariously employed, women especially. What does it mean if we center our analysis, looking at these women who are in survival jobs and cannot work from home, who are abused by their employers because they cannot speak English, and who are also sexualized based on their work? That is a way for us to build infrastructures within our community.

There’s also trying to address our own practices that perpetuate misogyny, like the class system for example. I always go back to looking at the systems of capitalism and white supremacy, etc. etc. That needs to be addressed and we cannot do that without a multiracial, multiclass alliance. We need to be building a movement that really goes into the core of that ideology.

If we really want systemic change, then we have to name the systems that perpetuate oppression. Capitalism, white supremacy, patriarchy, imperialism.

Alexander Sun ’23

Alexander Sun `23 spent his early childhood years in Beijing, China, before moving to the United States the summer of his high school freshman year. While he considers himself to be predominantly Chinese, he was influenced by U.S. culture through his primary and international middle school, knowing his family would eventually move back to the States.

The S&B: What was it like to become Asian American when you moved here?

Sun: The first day of high school, I was really surprised by how many Asians were at the school district, because after all, [San Marino] is primarily Asian. One of the weirdest things I experienced was the dichotomy between Asian Americans and just Asians. A term that is tossed around a lot in the San Gabriel Valley is “fob,” which is short for “fresh off the boat.” People thought I was one, because I had just moved from China, and the first response they had – even from Asian Americans – was, “Wow, your English is really good.” That’s something that always bothered me.

I also occasionally partook in that culture of looking at “fobs” as beneath us, because they weren’t as integrated or assimilated. And it was weird, looking back, because I’m not sure how that manifested.

(Editor’s Note: “Fob” is generally seen as a derogatory term for recent immigrants from Asia who look noticeably different.)

What was the dichotomy between Asians and Asian Americans like?

I remember a few friends and I were surprised when some of the Asians at San Marino didn’t know that much about their heritage. When we were covering the Vietnam War in my history class, a lot of students spoke about their families and what they learned, and I was surprised that they didn’t know it already.

In my experience, my grandparents always told me a lot about what life was like for them. They grew up under the nationalists during World War Two. In fact, my great grandparents on my mother’s side were nationalist agents. They were in [Chongqing] when the Imperial Japanese Air Force started bombing that area. And they fled, and thankfully they survived through the war, otherwise I wouldn’t be here. Those are the stories I grew up with.

Is there a pan-Asian American identity?

There’s a lot of casual racism in mainland China towards minority ethnic groups, and from the Japanese to the Koreans. There’s a lot of deep-rooted hate. And it’s to the point that, because of education and the way we’ve been raised, it’s almost become casual.

And not just ethnic groups. When we say, “Asian American,” a lot of people instantly think East Asian American. China, Japan, and Korea are seen as the big three. Even though there’s little Bangladesh, or the Nepalese immigrant population, but no one pays them as much attention as the big three. … A lot of it has to do with the gaze of other people. We know there are significant differences between us. But others don’t see it, and they don’t care. They’ll see us as Asian. It doesn’t matter where you’re from.

Is awareness enough to alleviate tensions between East Asian groups?

Awareness can lead to some of those issues being resolved, but you definitely need to go a step further. Japan, to this day, still hasn’t admitted any type of wrongdoing in World War Two, and that’s something that contributes significantly to the tensions between the Chinese and Japanese. In elementary school, we grew up watching propaganda films of World War Two, and they only referred to Japanese people as a racial slur. Awareness is a step in the right direction, but in order to truly ease tensions between Asian nations, you have to go a step further.

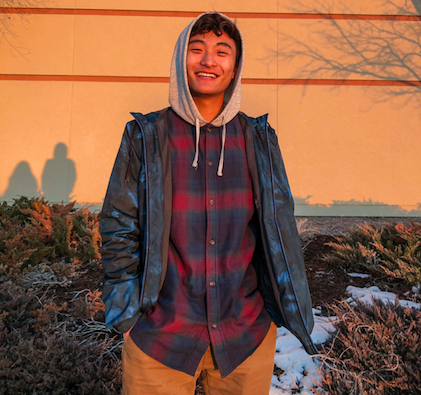

Jonah Shin ’22

Jonah Shin `22 grew up in a majority white community in Washington, with a similar racial breakdown to Grinnell. With the rise of overt AAPI discrimination, he hopes to hold Grinnell to a higher standard than the typical rural mentalities in his hometown.

Note: Interview was conducted by email.

The S&B: What kind of environment did you grow up in?

Shin: I struggled a lot between my Asian identity and my American identity. This struggle is what being “Asian American” has always meant to me; I think most Asian Americans (and other mixed races!) go through the exact same struggle at some point in their life, particularly if they grew up in a white community like I did. Being Asian American is acting a certain way in front around your Asian friends and then acting differently around your white friends. Sometimes it got to the point where I made self-deprecating racist jokes around my white friends because it was amusing to them (I no longer do that!). I do know a few Asian Americans who grew up in Asia and thus have no struggle with their Asian identity at all; I myself have always been envious of them.

How do you navigate the line between being discriminated against, while at the same time being a model minority?

My parents always taught me that “being a model minority is how to beat discrimination” because that’s what their parents taught them. I think the issue is a little deeper than that, but through my childhood, I tried to live by this philosophy. “White people can’t make fun of me if I’m better than them.”

What I came to realize though is that people didn’t really care about model minorities. When I was working at my old factory job a few summers ago, my coworkers would still poke fun at my race no matter what. If I beat them in a footrace, they would say it’s because I’m Asian; if I solved a math problem quickly in my head, they would say it’s because I’m Asian. Everything I did was “because I was Asian,” even if it didn’t make any sense. It sucked. Nowadays, I don’t really try to maintain any “model minority” façade because of this reason.

What does it mean to stand in solidarity with the AAPI community? What does a community of support look like to you?

To me, solidarity is going against the stereotypes. A community of AAPI support is not being “docile” or “passive” about Asian American discrimination.

More importantly, solidarity is speaking up. I think many AAPI-related microaggressions are exchanged everyday everywhere, and to me, standing in solidarity with AAPI means actually speaking up against these microaggressions. I have personally felt so relieved (most of the times) when somebody points out a microaggression that makes me uncomfortable.

How do you think of your identity now that you’re at Grinnell?

The Grinnell student body is diverse. That alone has made a huge difference compared to the environments I found myself before college. At Grinnell, I found the spaces where I feel comfortable, and the spaces where I don’t feel comfortable. I’m glad that the Grinnell community has given me that opportunity to explore where I want to be.

I found myself surrounded by other Asian Americans like me. Around other Asian Americans, I don’t feel like I have to act a certain way (mostly). This is vastly different from my high school/hometown experience. I hope this security can persist throughout my life no matter where I choose to live.

Isabel Lieb ’22

Isabel Lieb `22 is a Chinese adoptee who was born in China and moved to the United States when she was ten months old. She grew up in a diverse school district, where her parents wanted her to see more people who looked like her.

The S&B: Were there any differences between your home life and school life?

Lieb: When I was a kid, I would forget that I was Asian. It would only be until my parents dropped my off at grade school that people realized, “Oh, your parents are white. They’re not Asian.” It was one of those things that as a kid, if it never came up in conversation, it was never an issue. But if someone asked me, then I would say that I was adopted. I don’t know if that changed the perception of how my peers saw me. Among my friends, it never became a big talking point.

There was an understanding that we were local Asian Americans, so we were all going to be treated like Asian Americans. Especially given current events, I have become more aware of my Asianness.

How did you start realizing you were labeled as “Asian American?”

Growing up, I didn’t try to learn more, because it was never a part of my identity that was in question. It was only when I went to Grinnell and started seeing other Asian Americans, especially international students who grew up in China, where I realized, maybe I’m “less Chinese.”

So I’m like, okay, I’ll take a couple of Chinese classes. One of the first things you learn in class is how to introduce yourself, like “My name is…” and then “I’m an American,” “I’m Japanese,” “I’m Chinese,” and so on. When I spoke in class, I said I was Chinese. The teacher asked, “Are you from China?” I said yes. She asked, “Did you grow up in China?” I said no. Then she said, “Well, then you are American.”

I don’t think she meant it insensitively or had any malicious intent, I think she truly was not expecting it. The implication when you say you’re Chinese, is that you are an international student from China. It made me think that I was not Chinese, but Asian American.

Is there a pan-Asian American identity?

You may still be Asian, but that does not mean America is your nation. You could honestly be from any continent, but as long as it fits into the American schema of what they think, or if you are in dissonance with what the American schema believes an Asian person looks like, all of a sudden, you are treated differently.

It’s a slap in the face when you work your ass off, and then someone says it’s your genetics. Looking back, I would say to call out those lines on the spot. If you don’t say anything, then it will happen to someone else.

Have you had these conversations with other Grinnell students?

Honestly, my identity as an Asian American has been out of sight, out of mind until 2020, 2021. It’s a privilege for me. In March 2020, a student had posted on Facebook that someone had written “Go back to Wuhan” outside their door. And that was scary, because you realize another student wrote that. You’re like, “Oh gosh, I have to live with these people.” We left so quickly that there wasn’t any time to sit down and talk about how we’ve always been played off as the model minority, but that doesn’t mean we don’t face discrimination because of it. We never really got to have those meaningful conversations.

What does it look like stand in solidarity with the AAPI community?

It’s not just showing support for Asians who claim they are facing violence, because oftentimes, you can’t put yourself in their perspective. You have to take their word for it.

The narrative I’ve always heard is that Black people attacking Asian Americans are to blame. The underlying message there is that people are trying to get two groups to fight against each other, to ignore this overlying context that it is America we are all living under. You are fighting each other with the stereotypes America has made.

So, I would like to see more connectivity, especially with our Southeast and South Asian friends. They get left out of this talk even though they are just as Asian as the rest of us. I would love to see more Asians being open towards people who have nontraditional upbringings, and more Asians supporting their peers when they call out racism. And I would like to see more Asian men supporting Asian women. It’s become very apparent to me that people tend to gaslight Asian women more. From both a sexist and racist standpoint, within the Asian community, it’s helpful if we all have each other’s backs, and are willing to recognize each other as Asian. We face – maybe different iterations – but the same kind of adversity within this American context.