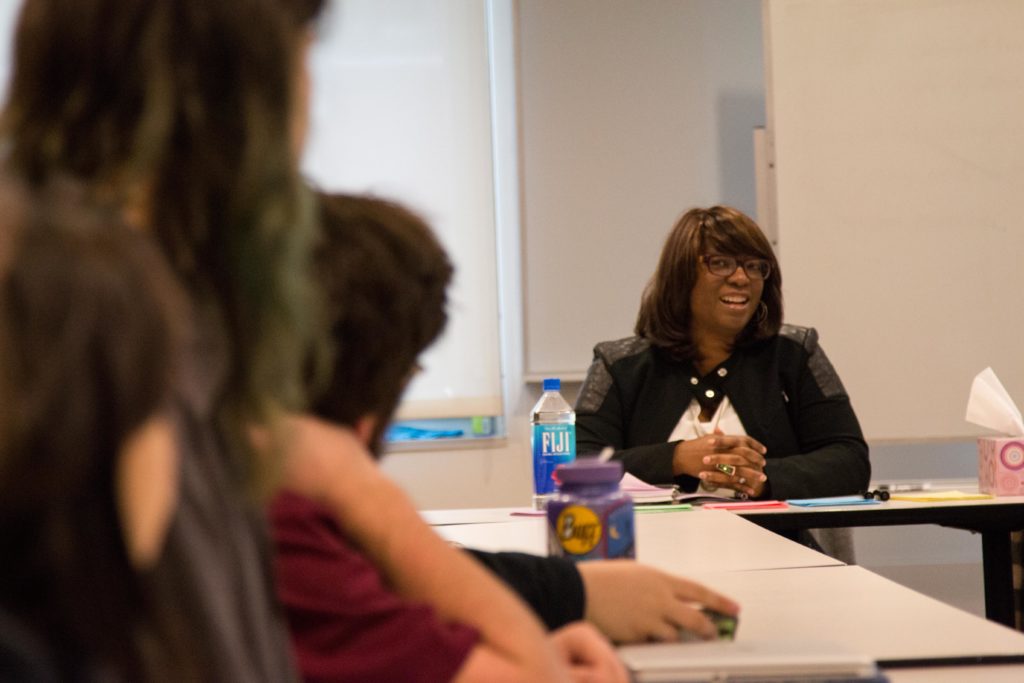

Nichelle Tramble Spellman is an award winning crime novelist. She has published two novels, and has also developed films and television projects with HBO, F/X. Dreamworks and Warner Brothers. Spellman sat down with the S&B’s Emma Cibula to talk about genre, Hollywood and the politics of writing.

The S&B: What draws you to the crime/noir genre?

Nichelle Tramble Spellman: Well, with “The Dying Ground”, I initially wrote that as a coming-of-age novel. And there was a murder element in it that was, to use a TV term, a C-story. And during the rewriting process, the murder was brought up to become the A-story and drive the entire book. And once I made that decision, I stopped for a while, and spent about six months just really reading in that genre, and then I fell in love with it and sort of embraced crime fiction, and that ended up being a natural habitat for me.

The S&B: Do you see yourself as a traditional crime noir novelist or do you think your work departs from the genre in any way?

NTS: I think it departs a little bit, in the first book specifically, because the coming-of-age element was so huge. And I think the second book, “The Last King”, is more straight-forward crime fiction, which I really embraced and really enjoyed. The crime novel gives you an opportunity to comment on larger social issues within a genre.

The S&B: What are your biggest inspirations when it comes to brainstorming ideas for your books?

NTS: Reading. Yeah, reading. It’s usually like the seed of an idea about a character in a certain situation and how they would react. And I keep clip files, some are like 15, 20 years old of story ideas and story nuggets that I think “Oh, that might be interesting to revisit that someday.” And whether it comes from an article I read in a magazine, a newspaper, a story I overheard, something someone told me, a nonfiction book that kind of plants the seed of an idea, it sort of comes from anywhere.

The S&B: Do you find writing humor or writing drama more difficult? Which do you find more interesting or rewarding?

NTS: I don’t write a lot of comedy. I think the jokes that are there, I wasn’t planning on them, it just comes out of characters and how they react to a situation or the language that they use or the phrases that they use or something. I’m not a straightforward comedy writer, through. I think comedy is very tough.

The S&B: What’s the biggest difference you see between writing for TV and writing novels?

NTS: Well, writing the novels, it was just so singular. It was just really intimate and personal and it was just me and a blank page, and I steered the ship and decided what the story was, who these characters were and where they were going. And TV writing was completely collaborative from the beginning. You’re in a room full of other writers who have the same weight as you, story-wise, and then you have a show-runner who connects your ideas, so it’s a process that’s filled with other people. And once you go outside the writers’ room, you have the network and the studio who weigh in, and once it goes from there, you have the cast that weighs in, so it’s not an arena where you can be as precious about your work. You really get to flex your muscle and move any way you want when you’re writing a book.

The S&B: You talked a little bit about experiencing sexism in the writers’ room. Can you offer any advice to young writers that might have to face that or any other oppressive “isms” in Hollywood?

NTS: You know, none of the circumstances have been overt, because I’ve had the luck of working with really good people. I think it’s about retraining people how they react to you, how they react to a situation and sort of retraining. And we used humor to sort of break through a situation that was uncomfortable or that could be viewed as sexist or racist. Like, just shining a light on the behavior, but in a humorous way, which lands softer and makes the point, and doesn’t turn it into a contentious situation that stops the room, stops the flow of work, or turns it into a toxic environment. There are some situations that are going to be uncomfortable, and when you’re a lower level writer, you don’t have as much of an opportunity to fix it. So, you hope that you work for a show-runner that says, “no way, not cool.” You will actually, as you work in the business, kind of know places where that kind of behavior is the standard, and if you can, you just don’t work with those people.

The S&B: Do you see an importance in writing for TV shows with broad audience bases in today’s political climate?

NTS: I think that there is—we had a political round table after the election where a lot of voice was given to artists and writers and musicians and creative people being the voice that helps bridge the gap. I think that television is powerful in that it allows you to see people beyond the “other.” And I think when we have a world where you can kind of go off in your own corner on the Internet, and not really interact in any real way with people, you forget the very basic human things of, one, decent behavior and decent thought and not being horrible, and if there’s an opportunity just to softly place that there in someone’s home before they realize what happened, it’s subversive, in like a very good, entertaining way. It’s hard to talk about it being a big deal, because you see black families all the time on television now, but when The Cosby Show came out, it was huge to see an upper-middle class black family on TV. Like, there was even a debate as to whether or not they existed in the real world, and now you don’t even think twice about it. So, I think there’s a huge opportunity for artists to kind of be a part of the healing process.