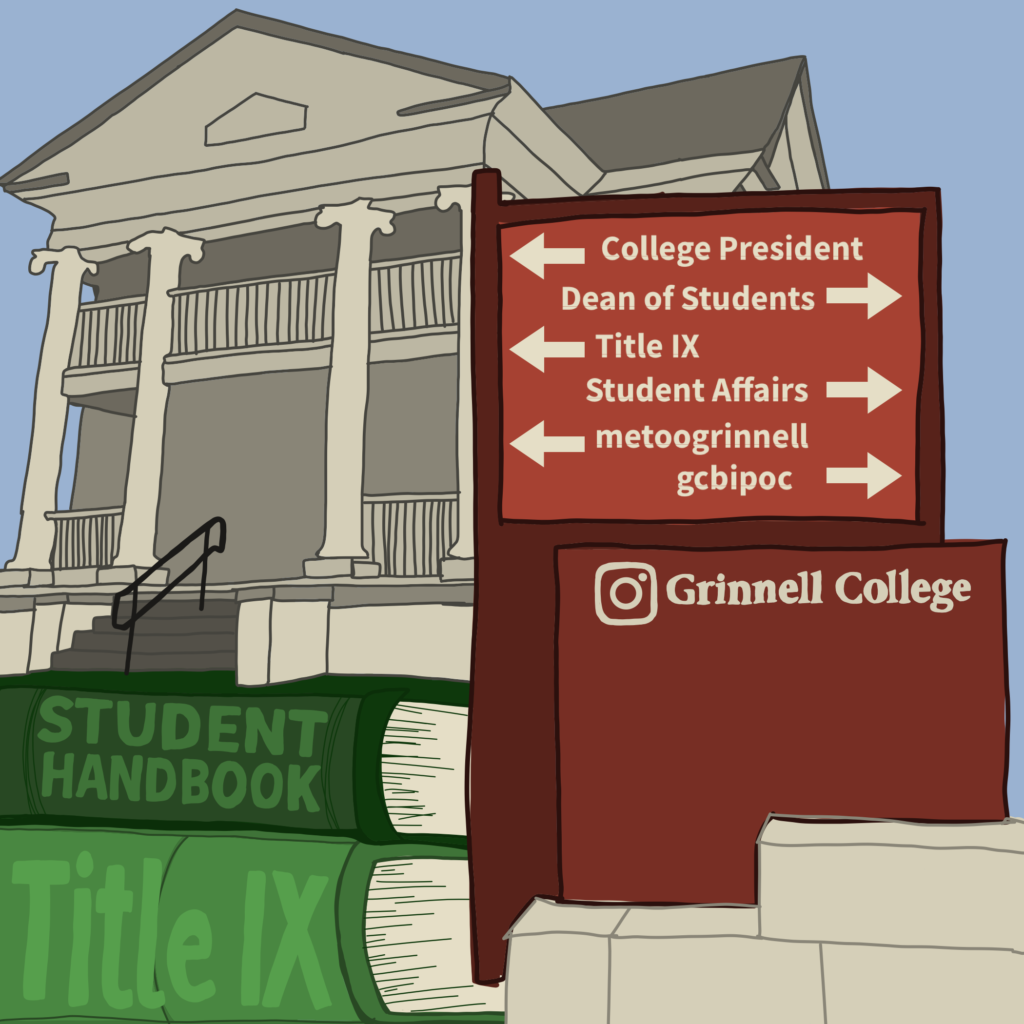

Scattered across the globe this summer, Grinnellians took to social media in the midst of a global social movement in which thousands across the country gathered to protest centuries of violence against the Black community. On the newly created Instagram account Amplify BIPOC (@gcbipoc) direct accusations aimed at students and faculty rose to the surface, testifying to the burdens that Black, Indigenous and People Of Color (BIPOC) students carry while on campus.

Soon, another online activist page, the unaffiliated account Me Too Grinnell (@metoogrinnell) followed.

The accounts act as platforms for a mix of anonymous and non-anonymous posts from students who say they have experienced racial bias and harassment (submitted to Amplify BIPOC) as well as sexual assault (submitted to Me Too Grinnell) on Grinnell’s campus or online community.

The stories on both pages are harrowing; the raw pain of the student community unfolds through bolded text and five-page slides recounting the suffering that many people have faced while on campus.

One post submitted to Amplify BIPOC under the name “Loud and Proud Woman of Color” says, “Having white men look down on me and my friends everytime we worked or did any of the things one has to do to survive Grinnell and the expenses was demeaning and strengthened the maid complex in my head. It made us feel like we were meant to serve, clean, cook, and do the several things people attach to being women of color, and it was disgusting. This makes me feel angry, hurt, betrayed, ashamed, and embarrassed. This has left me feeling inferior, like we will never be equal in their eyes. @Sportos y’all need to wake the heck up and take accountability because it’s time.” Sportos is a term used within the Grinnell student community to refer to members of sports teams.

An anonymous post on Me Too Grinnell reads, “I will never forget those of u who stood by my rapist in 2018.”

The Grinnell-specific accounts parallel numerous other Instagram pages started this summer that seek to reveal the hardships and violence that BIPOC communities face on school campuses across the country. Unofficial testimonials came from higher-education institutions like Columbia University (@truecolorsofcolumbia) and Bowdoin College (@blackatbowdoin) to private K-12 schools such as the Brearley School (@blackatbrearley) and the Dalton School (@blackatdalton) in New York City.

What makes the Grinnell-specific accounts unique is that posts often directly name the perpetrator of the incident described. Posts such as these are generally referred to as “call-outs” on social media. Between the months of June and September, the Amplify BIPOC and Me Too Grinnell handlers posted 180 and 150 posts, respectively, many of which were call-outs.

In the case of Amplify BIPOC, three anonymous handlers have the role of sifting through confessionals. They are the only people who can directly post. The three began the page in late June and modeled their platform after a previously existing page within the Grinnell community.

Amplify BIPOC was meant to open a space for the Grinnell BIPOC community to share their experiences in a safe manner as well as to uplift members of the BIPOC community, said one handler, who did not reveal their identity to The S&B due to concerns for their safety.

The page, however, quickly caught the attention of the student community; throughout the month of July, the handlers posted close to once a day and sometimes more often. As confessionals rolled in, many familiar student names began to appear. The interviewed handler said, “The intention for the page wasn’t just for it to be call-outs, and I think it does serve other purposes, but we are okay with it being known for call-outs because at least there’s a space for that.”

The anonymous handler said that the page “tried to unpack the experiences, we try to give some background information, so there is an aspect of learning, so you’re not just sitting with people’s trauma not knowing why they’re saying this.”

Tactics like this allow for those who have experienced racism to share their stories in a cathartic and honest manner, while also providing the people named as perpetrators with a means of education on how and why their actions contained racial bias and microaggressive remarks.

A month after Amplify BIPOC’s rise to online prominence in the Grinnell student community, Emily Louden ’22 started the Me Too Grinnell account.

Louden was inspired by their own negative experience with the Title IX office, where they say they faced gaslighting, a form of manipulation that makes a person question the validity behind their own thoughts and experiences, from members of the Title IX office, specifically from Dean of Students Ben Newhouse, when they came forward about having been sexually assaulted.

Like the handlers of Amplify BIPOC, Louden wanted to provide a space for survivors to hold their perpetrators accountable and to make their stories heard by the greater student community.

“The most rewarding and the hardest part has been just the sheer volume of people who message me with stories,” they said. “That’s a lot of emotional burden to have. … At the same time, the fact that people are willing to come forward with their stories is really powerful.”

Both pages bring up questions not only about Grinnell campus culture, but the current state of the College’s administrative policies and procedures intended to respond to bias-related incidents. In a survey made and distributed by Louden through the page, anonymous respondents stated various mixed and negative reviews when asked about their experience through the Title IX office.

One respondent wrote, “The two people I know [who] got cited for Title IX issues remained on campus with seemingly no consequences, so I’m not quite sure what the Title IX office actually does.”

Another respondent wrote, “I don’t feel comfortable knowing that there are people with multiple Title IX reports filed against them but they are still on campus or on probation. It is not fair for victims and others who could potentially be victims to have to see these people and go on like the offense did not happen. It is extremely unfair and shows a lack of seriousness and vigilance on part of the administration of this college.”

Louden supported the sentiments behind these responses. “Right now, people aren’t going to Title IX because they know what happens when you go and that’s that you get invalidated, your case doesn’t go forward and the person who assaulted you now knows that you are making claims against them,” she said.

The Title IX process is multi-step and legally complex. Bailey Asberry, Title IX Coordinator, emphasized the College’s use of third party associates such as Husch Blackwell Company, who assist with the interviews of both the survivor and the accused party, as well as former Iowa Supreme Court Justice Marsha Ternus, who serves as the adjudicator for investigations. Ternus ultimately determines whether the accused party will be found responsible.

Asberry said she feels for those who have gone through conduct processes. “Inevitably, a party is going to walk away from a conduct process disappointed … because we have to make a finding, we have to make a decision.”

She emphasized the resources available to survivors outside of investigative hearings, including mutual no contact orders and mental health resources such as counseling through Student Health and Wellness (SHAW).

Asberry also emphasized her openness to feedback. “I’m always, always open to hearing feedback. I think that’s really important. I don’t think that you can ever look at what you do, whether it’s Title IX or something else, right, you can’t just say ‘I’ve got it all figured out and I’m good.’ You have to be open to hearing concerns and feedback and suggestions.”

In contrast to students’ grievances with Title IX, the issues that arose from Amplify BIPOC have allowed students to put pressure on the administration for policy changes concerning anti-racism and racial bias.

In an editorial published this past August, Raven McClendon ’22 and Errol Blackstone ’20 put forth 14 demands towards anti-racist action by the College, including that the College fund an anti-racist task force made up of students, that the SEPC (Student Educational Policy Committee) Coordinator or SEPC members for academic departments be granted the ability to observe and evaluate professors/classes and that the Student Handbook be rewritten.

Newhouse wrote in an email to The S&B, “We’ve taken note of the policy recommendations shared via the account [Amplify BIPOC] and are taking them into consideration along with information and recommendations we’ve gotten through other avenues as we identify anti-racist practices to pursue at Grinnell.”

The College’s executive faculty banned the use of the n-word in all academic activities at the beginning of this semester. The blanket ban, which included Black students and professors as people not allowed to use the n-word, was poorly received by students.

Although Newhouse aligns himself with the student community, Louden said one of their desires for the future was that “people like Ben Newhouse … respond to the criticism and the hurt that they have caused.” Ben Newhouse is named in two posts on Me Too Grinnell.

Louden added that over the past few months, they have also had to navigate issues of “false allegations” towards students named as being enablers of sexual assailants, which tended to target the South Asian community, particularly with generalized accusations of enabling behavior without specific details and relating to students with minimal or no personal connection to the accused assaulter. Louden said that the page had received 201 submissions, but many of them could not be posted due to the racist and unfounded nature of the accusations.

One of Louden’s advisors for the page, who helped them sift through confessionals and offered advice on how to navigate the social discourse on the page, said, “I think that especially with white people on campus, they seek people to blame rather quickly.” The page advisor asked to stay anonymous due to concerns for their safety.

Asberry also commented on how intersectionality affects in sexual assault and harassment conduct processes. “Thinking about the intersecting identities, and how so much of our sexual harassment prevention work is focused on what works for white women, and it doesn’t work for other women of color, it doesn’t work for other identities, and so we’ve got to be always thinking about what does our process do and how does it help or not help people,” she said .

The anonymous Me Too Grinnell advisor added that they think students have difficulty calling out their friends or people within their social sphere or immediate community. “I think call-outs within a community, like within your own community, are really important, and a lot of people don’t wanna do that so they seek to call out other communities,” they said. “And I think that’s incredibly harmful.”

Further, the tool of “call-outs,” themselves have raised debate not just within specific communities, but as an entire culture that plays a significant role within online communities such as these Instagram pages. Call-out culture, in some people’s eyes, breeds a toxic, hateful environment and ignores any potential for education.

A student who was “called out” in a Me Too Grinnell post for harassment and inappropriate touching, who asked to be anonymous due to concerns of retaliation, questioned the productivity of such methods. The student said that they advocated for a “call-in” rather than a “call-out” approach: “The philosophy behind this acknowledges that, “Hey, I recognize that you’re a person, who had an upbringing and has a lot of complex ideas and emotions.”

In response to this, the anonymous Amplify BIPOC handler asked, “What has been more productive [than the call-out posts]?”

As of now, other than raising student awareness of incidents and accused perpetrators of harassment and assault, there has been no specific change to College policy as a result of call-out posts on either account. In the student sphere, then-VPSA Amelia Zoernig stepped down from the role after receiving criticism on Amplify BIPOC for her handling of an event proposal in fall 2019.

Beyond the names of accused perpetrators of harassment and assault, the confessionals on the Instagram pages have revealed not only existing tensions within the student community on campus, but also holes within the College’s current policies. The discourse has ultimately led to online action on the part of the account handlers and other student participants alike, but students are still waiting for future improved anti-racist and intersectional policies.