For the past month, community members in the City of Grinnell and Grinnell College have grappled with the question of gun safety and regulation in the midst of a debate that has become deeply polarized. “26 Days of Action Against Gun Violence,” the resulting month-long series of talks, community meetings and demonstrations, has drawn the attention of prominent gun safety advocates, including the director and producer of the critically-acclaimed 2016 documentary “Newtown.”

Director Kim Snyder and producer Maria Cuomo Cole will join Newtown residents impacted by the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting for a screening of the film in the Harris Center next Tuesday. The event follows last week’s Community Hour in which College professors discussed the political, constitutional and social nuances of the ongoing debate around gun violence in the U.S.

Snyder sees the screening of the documentary as an opportunity to generate further dialogue about the issue of gun violence and legislation.

“Grinnell reached out to us from a number of concerned voices and community voices who said, ‘We are thinking about this five-year marker [of the Sandy Hook shooting] and we would like to show the film here.’ … I think it’s representative of dinner tables across America that want to talk about this in a way that is civil and not polarized,” Synder said.

Professor Eliza Willis, political science, who has worked on the month of events in the community, also emphasized the role that dialogue — representing a range of perspectives — must play in the pursuit of gun reform.

“[We are] really trying to attract the attention of gun owners who care about responsible gun ownership and responsible gun safety. … We’re about pro-safety, anti-violence. Our desire is to make this a dialogue. … I think that many gun owners would be receptive to the idea that concealed carry should be based on local law and not a piece of national legislation,” Willis said.

The activism around gun violence in the City of Grinnell represents a unique instance of sustained advocacy on the issue; typically, outrage fueled by mass shootings loses steam quickly after a national crisis such as the shooting in Las Vegas last month.

“[Social regulation policies] tend to have a little bit of a pattern. … They tend to have a crisis stage, outrage — there’s action on that, and then people who oppose it react just as strongly, or maybe more strongly. And then they tend to hit a stalling point, often because public attention moves on,” said Professor Doug Hess, political science, at the Community Hour last Tuesday.

Grinnell is unique, too, in its proximity to National Rifle Association (NRA) president Pete Brownell, who lives in Grinnell and maintains strong social and economic ties to the city. The 26 Days of Action has followed community efforts to engage Brownell in a conversation about the NRA and his role in the organization.

“Somebody wrote a letter that they thought could be delivered to [Brownell] asking him to meet with members of the community. The way it was presented was as neighbors of his, wanting to talk about his role in the gun safety issue. … It ended up that we passed it around and 170 people signed it,” Willis said.

Changing the discourse around gun control could potentially foster the kind of conversation that organizers in Grinnell are seeking.

“If we could enlist gun owners to sit down and have civil conversations about the fact that we have a problem with gun violence in the country and that it’s not about a threat to Second Amendment rights, but about trying to as fellow citizens that want to protect children, how to address this, that would be the greatest thing we can say the film has played a part in fostering,” Snyder said.

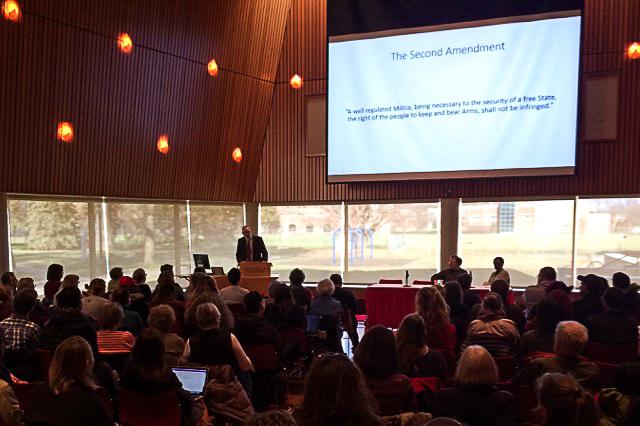

Last week’s Community Hour on the Second Amendment, sponsored by the Rosenfield Program and organized by faculty and community activists, was designed to prompt this kind of dialogue. The event featured talks by Professors Kesho Scott, sociology and American studies, Peter Hanson, political science and Doug Hess, political science.

Hanson, who teaches constitutional law, spoke about the history of the Second Amendment, and concluded that the question of gun control will be determined politically.

“The problem with gun control is not primarily a constitutional problem. It’s a political problem. According to the court’s most famous conservative justice, Antonin Scalia, the constitution and the Second Amendment permit reasonable gun regulations. Gun rights have become politically sacrosanct only because the NRA has the ability to successfully mobilize its members and put political pressure on politicians,” Hanson said.

Scott wrapped up the event with a personal and historical perspective on the issue of gun control, pointing out the racial politics of gun ownership in the United States.

“The Black Panther Party explained to me why U.S. violence was against my race, my community and people of color. It also explained why U.S. violence was really an American norm. Therefore in my mind, it was necessary that Black people in America defend themselves. It is in that context that the Second Amendment was my right and from my family beliefs and community values, it was also my responsibility. … On my 18th birthday I purchased an 8 gauge 12-pump shotgun that was then the deadliest legal self-defense weapon. Frankly my actions were dictated because I felt defenseless,” Scott said.

Scott has since reconsidered her position on gun sales and ownership.

“We need to move forward. Because my only option to defend myself and maintain my civil rights, whether it’s freedom of association, speech or economic pursuits without government intervention, are impacted by technological gun innovations that allow for 500 people to be injured in 11 minutes. And my gun purchase, and all of those gun purchases, contribute to the Sandy Hook massacre and other massacres.”