Shouldn’t student happiness be the simplest reflection of whether a college is “good” or not?

April 17, 2023

2023 Iowa College Media Association award winner, Third Place – Best Print/Online Opinion

When I was accepted into Grinnell College, the first thing I did was look at its ranking. As I weighed my options and approached a final decision, I subconsciously compared schools based on my perception of their prestige. While rankings were far from the only factor in my eventual selection of Grinnell, they certainly played a role in my choice.

In the U.S. News and World Report, the alleged gold-standard for college rankings, Grinnell College currently ranks #15 out of over 200 liberal arts colleges across the United States. The ranking position prompts a seemingly simple takeaway — Grinnell College is worse than 14 other liberal arts colleges, and it is better than the majority. Yet, this interpretation is a gross simplification of what it means for a college to be “good.”

As soon as U.S. News began placing colleges into an ordered list, it created an assumption that some schools are inherently better than others. However, the establishment of the “best colleges,” which is intended to be an objective list, is based on a subjective methodology.

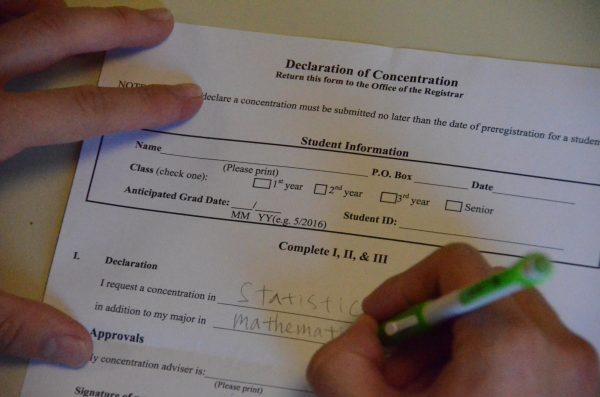

According to U.S. News, a fifth of each college’s overall grade is based on “expert opinion” and “academic reputation.” For liberal arts colleges, this score is calculated by sending a comprehensive list of all the liberal arts colleges in the country to each college’s president, provost and dean of admissions. At each participating school, these three individuals rank the hundreds of schools on a scale of one to five. The average score of all respondents then becomes 20% of the ranking equation.

This process raises the question of how these three individuals possibly know enough about the other colleges to accurately score their reputation. If most of these individuals are delegating scores without knowing meaningful details about the college, it is likely that they are simply relying on the prior year’s rankings to guide their perception of reputation.

As a result, the rankings process becomes cyclical. The colleges at the top of the list generally remain at the top because their high ranking gives them a good reputation, and their good reputation subsequently gives them a high ranking again the next year.

Much of the other data that U.S. News uses — graduation rate, financial resources and student selectivity — fail to reveal any substantive information about the actual quality of an institution. This data does not indicate, for example, why the graduation rate is high or low, how accessible or inaccessible resources are to students or whether selectivity comes at the cost of diversity.

Because U.S. News attempts to be both heterogeneous, comparing colleges of all sizes, locations, etc., and comprehensive, comparing across multiple variables, it ultimately fails to create an effective or useful ranking.

Despite the recent news of many top law schools no longer submitting data to U.S. News, I highly doubt that there will be a widespread rejection of rankings. After all, highly ranked colleges have a significant incentive to preserve rankings — the higher rated they are, the more applicants they are likely to receive.

Consequently, I believe that the most realistic step is for colleges to insist that U.S. News adapts its methodology to better reflect the quality of student experience at a college. This could mean that a college’s acceptance rate, test scores, post-grad income, alumni giving rate and overall reputation are given less weight.

Instead, rankings could take into account the day-to-day variables that affect student experience, including class size, one-on-one time with professors, research opportunities, funding for individual opportunities, availability of advisors, access to mental health resources, advocacy opportunities, interaction with the community, frequency of interaction with students from different backgrounds, ideological diversity and LGBTQ+ inclusivity. This change also requires an acknowledgement that qualitative data is equally critical to rankings as quantitative data. In fact, student happiness may be the simplest reflection of whether a college is “good” or not.

In my eyes, the increasing focus on college rankings has caused a misguided aspiration for students to attend one of the “top-ranked” national colleges and universities regardless of the cost or actual academic experience.

In addition, at colleges where financial status is included in the acceptance process, a larger applicant pool may cause a rise in tuition as more applicants would be willing and able to pay full tuition or close to it. When this happens, the college tends to become less accessible for low-income students who cannot contribute as much money, potentially leading to a decrease in diversity.

The reliance on current college rankings may be comfortable, but it certainly is not the best approach to determining the quality of the experience that a college offers. Until the methodology is changed, colleges like Grinnell will continue to prioritize variables that are important to rankings but not important to students. Some colleges actively attempt to lower their acceptance rate strictly because they will rise in the rankings, even though the acceptance rate has little to no effect on student experience.

At Grinnell, for example, I would argue that there is a correlation between the lowering acceptance rate and changes in the character of campus. Many alumni talk about how they actively sought out Grinnell because they were attracted to its academics, intentional community, self-governance, social-justice mindset and ethics. Now, I hear many students indicating that they choose Grinnell simply because of its high ranking and national reputation. It creates an interesting tension — some students are here for the experience while others are here predominantly for the prestige. It seems as if Grinnell is no longer the first choice of many students here. Instead, Grinnell may simply have been the highest ranked college they were accepted to. However, since the rankings do not account for student experience, many of those students may end up unhappy at Grinnell. According to the College’s 2022 Art and Science Persistence Study, 47% of 401 surveyed respondents indicated that they had considered leaving at some point during their time at Grinnell. Not only are these students potentially unhappy, but they also may be occupying spaces that would be better filled by applicants who want Grinnell College for the experience, not the prestige.

Colleges should demand an overhaul of the ranking methodology so that they can focus their resources on variables that more directly impact the lives of students. For Grinnell, this could be an increase in funding for student initiatives, prioritizing community interaction or, with enough luck, putting up more hammocks.