For Professor Amanda Lee, dance is a form of resistance. With a research specialty in dance as a mode of performing identity, she sees workshops as an opportunity to unify and educate about the Jewish diaspora.

In her recent visit to Grinnell, she did just that, hosting a Jewish Dance Workshop in the Bear’s dance studio on March 9. Lee led a group of just over a dozen Grinnell students through a combination of various folk and contemporary dance exercises.

The workshop was characterized by high-energy group dances, such as one in which participants rotated with one another in a circle, performing a series of arm movements and footwork.

Lee started off slow, speeding up and adding additional movements once the group began to get the hang of the dance. Even so, she prioritized individual comfort, encouraging students to alter dances as needed to fit their body.

“Modifications are just an opportunity for more interesting movement,” said Lee.

Between dances, Lee sat with the students and encouraged them to think about the nature and tone of the dances. Many of the dances emphasize group work and celebration, which Lee uses as a means of defying oppression.

She taught one dance in particular which she learned from her grandmother, who belonged to a predominantly Jewish dance group in New York in the 1930s. Participants broke off into groups and used movement to, as Lee said, “reach that moment of transcendence” and “release from oppression.”

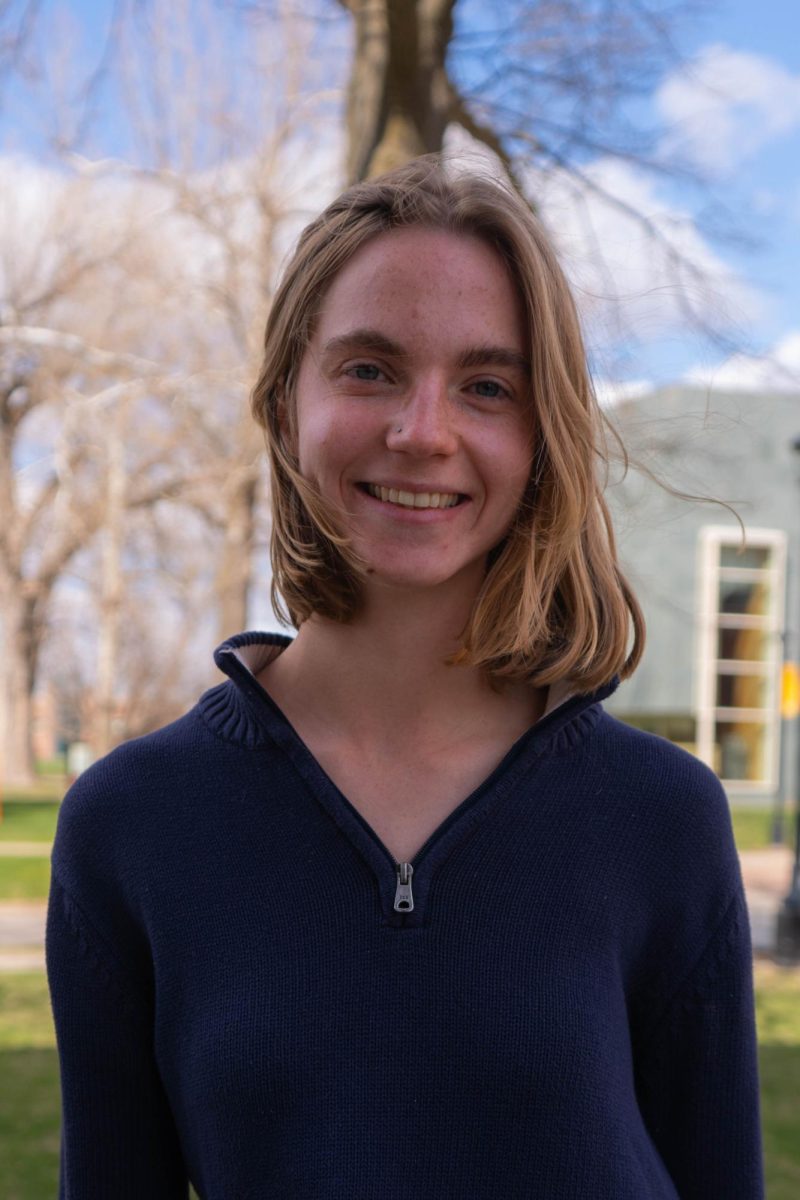

Professor Lee taught at Grinnell as a visiting assistant professor of French from 2019-2021 before moving to Boston University, where she works now as a visiting assistant professor of French and Performance Studies.

Lee was referred to Chaverim student leader Lila Podgainy `23 while visiting assistant professor of German Studies Viktoria Pötzl, who she met while working at Grinnell. They quickly worked to plan an event to provide a unique opportunity for cultural education.

“Jewish students on this campus do things and have a culture that’s beyond just religion,” says Podgainy, “and one that the school doesn’t really recognize often.”

Beyond dance being a facet of most Jewish celebrations, it has also served as a form of preserving cultural identity in times of struggle. Lee cites the formation of leftist Jewish dance groups, like that of her grandmother, which formed in the 1930s and 40s amid a rising wave of antisemitism.

“They [the dance groups] saw a broader mission of creating a consciousness in their dancers who were also workers,” she says.

Judaism is far from the only culture to use dance in this way. Lee is currently studying a form of European contra dance and ritualistic practice inspired by communities in Martinique called bélé dance, commonly used as a form of protest and preservation of African identity.

She cites Sonia Gollance, a German-Jewish studies scholar who studies 18th and 19th century Yiddish dance, and Katherine Dunham, who used dance as a means to further Black social activism in 1930s America, as examples of protest through dance that inspire Lee in her own work.

Across culture and history, Lee sees dance as “allowing them [dancers and dance groups] to access their personal experiences through embodiment … to then evoke their own political power through embodiment.”

Her goal is that students come away from her workshops with a new sense of how to use motion to inspire their daily lives.

“I hope that they experience a rush of ecstatic joy that I experience when practicing folk dance.”