Students, faculty and friends gathered in the Grinnell College Museum of Art this past Thursday, Nov. 11 for the momentous book release celebration of “Did We Make It?,” a chapbook of ekphrastic poetry published by Professor Ralph Savarese, English, and Tilly Woodward, curator of academic and community outreach at the Grinnell College Museum of Art. The creative project, which Savarese and Woodward began working on during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, was published in the “Hole In The Head Review” this past June and contains a beautiful array of poems written in response to 13 evocative, intriguing and finely-detailed oil paintings.

“Being an artist is lonely,” said Savarese. “Then you add the pandemic, and how is collaboration, both an engine of creativity, but also a way of ameliorating, lessening that sense of being alone?”

The occasion marked the final session of Writers@Grinnell for the fall 2021 semester. Director of Writers@Grinnell, Associate Professor Dean Bakopoulos, English, welcomed guests to the event and proudly introduced Savarase and Woodward.

“To be able to welcome two colleagues who’ve maintained … nationally acclaimed creative practices in the midst of all the work we do here is truly inspiring to me.”

Bakopoulos will be on sabbatical next semester, and will be handing the directorship of Writers@Grinnell during the spring over to Savarese.

Savarese is the author of three books of poems, two books of prose and has co-edited three collections of work.

Woodward is a well-known and highly praised painter for her hyper-realist and meticulously detailed oil paintings that feature images of nests, fruits, flowers, hands and more.

The two creatives have known each other for years, and both remarked on the great respect they have for one another’s work.

“Did We Make It?” is a collaborative work that consists of a photo collection of paintings by Woodward, and poems written by Savarese. Savarese emphasized that each poem was a response to Woodward’s art, rather than a description of it.

During the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, Woodward reached out to Savarese and asked if he would be interested in working on an ekphrastic project together. Savarese immediately agreed.

At the event Savarese credited his son, who had previously produced his own chapbook of ekphrastic poetry, for supporting him when the opportunity first presented itself and had told him, “Dad, I think you can do this.”

By August of 2020, the project was fully underway.

When asked why she reached out to Savarese for collaboration, Woodward said she recognized parallels between her and Savarese’s lives, particularly their childhoods. In addition, she was fond of the connections between their work, “both in terms of trying to support people and lift them up and to help them connect with being the best and fullest people that they can be.”

At the event, Savarese began by reading from the preface of “Did We Make It?”.

“It’s no coincidence that this volume was produced during the pandemic. Alienated from one another, stuck in our houses or apartments, worried about the future, we all, I think, dreamt of bridges,” read Savarese.

Initially, Savarese says he was intimated by the “level of craft” and detail that characterized Woodward’s paintings.

“Her paintings are so composed, so still, and yet at the same time so dynamic and otherworldly. I was attracted to their drama. Realism is anything but ordinary,” read Savarese from the preface.

Savarese said he wondered if his poetry, in response, should also have hyper-realist elements.

“I put that away and said … ‘What did these paintings do to me, my memory and my own sense of craft?’” said Savarese.

Woodward and Savarese did not discuss the selected paintings beforehand. Savarese chose which paintings he wanted to respond to from Woodward’s website rather quickly, not questioning or overthinking why he was drawn to particular images. One by one, Savarese workshopped drafts of poems for each painting and then shared them with Woodward for collaboration and revision.

“What I loved about our process was that it preserved a certain element of privacy. Each of us working alone, but then at key moments really opened it up into something that was generative,” said Savarese.

“The great discovery for me,” he explained, “was learning that by collaborating with someone, there could be less of me. And when there was less of me, I could relax and discover new possibilities more quickly.”

Woodward said that before reading the first drafts of Savarese’s poetry for the project, she wondered if the metaphors she had in mind when creating each painting had been powerful enough to get across.

“It was uncanny to me in some ways how closely his words would connect to things that he didn’t know or couldn’t know about the motivations for the paintings which I think really speaks to Ralph’s ability to craft a metaphor, to see keenly, to process life through words, and also made me feel that what I was investing in the paintings of myself was speaking out, which was rewarding,” said Woodward.

“Did We Make It?” also includes a video element in which Savarese, his son, as well as Woodward and her son, read the poems included in the chapbook aloud in a voiceover as images of the oil paintings fade in and out, meshing together and overlaying one another.

Experimenting with the video aspect of the project was something new to Woodward and explored another level of interpretation. While Woodward would have originally been inclined to overlay the video with a mellow musical track by a composer like Bach, Savarese encouraged her to have a different musical interpretation, one that was bolder.

“Here’s somebody who’s seeing, hearing, suggesting something very, very differently, musically, than my interpretation. And is this okay? Am I okay with that?” said Woodward.

Eventually, Woodward appreciated Savarese’s unique perspective and the pair settled on the musical work of composer Joseph Dangerfield.

“It’s really wonderful to have both a collaborator and also to have a critic whose ideas and thinking that you value,” said Woodward.

For both Savarese and Woodward, the collaborative process was incredibly rewarding and a way to connect creatively during a year apart.

“During the pandemic, when we were so estranged from one another, this was also just a kind of godsend on just a basic human level to be having this kind of connection,” said Savarese. “Tilly is the most talented human in Iowa. These paintings are absolutely extraordinary. The level of craft … it’s realism plus something, and so for me to be offered an opportunity to collaborate with Tilly Woodward, I mean, you know, ask me again tomorrow.”

The following section features the poem-painting duos that were featured at Writers@Grinnell. They are accompanied by the comments Savarese and Woodward made during the event and in an interview with the S&B after the reading. These quotations have been edited for brevity and clarity. The photos and poems were contributed by Woodward and Savarese. The complete chapbook and collection can be found here.

On ekphrastic poetry:

Savarese: It’s not a translation of the work. It’s a response to the work. It has to be faithful to elements in the painting, but it’s got to be its own thing. There’s got to be tension and some kind of space between the two. In our conversations, we more fully elaborated for ourselves what that relationship was like and it was really pleasing and stimulating to discover that more fully.

Editor’s note: This article has been updated to accurately print the poem “ABACURSE.” Updated Nov. 22, 2021, 10:05 a.m.

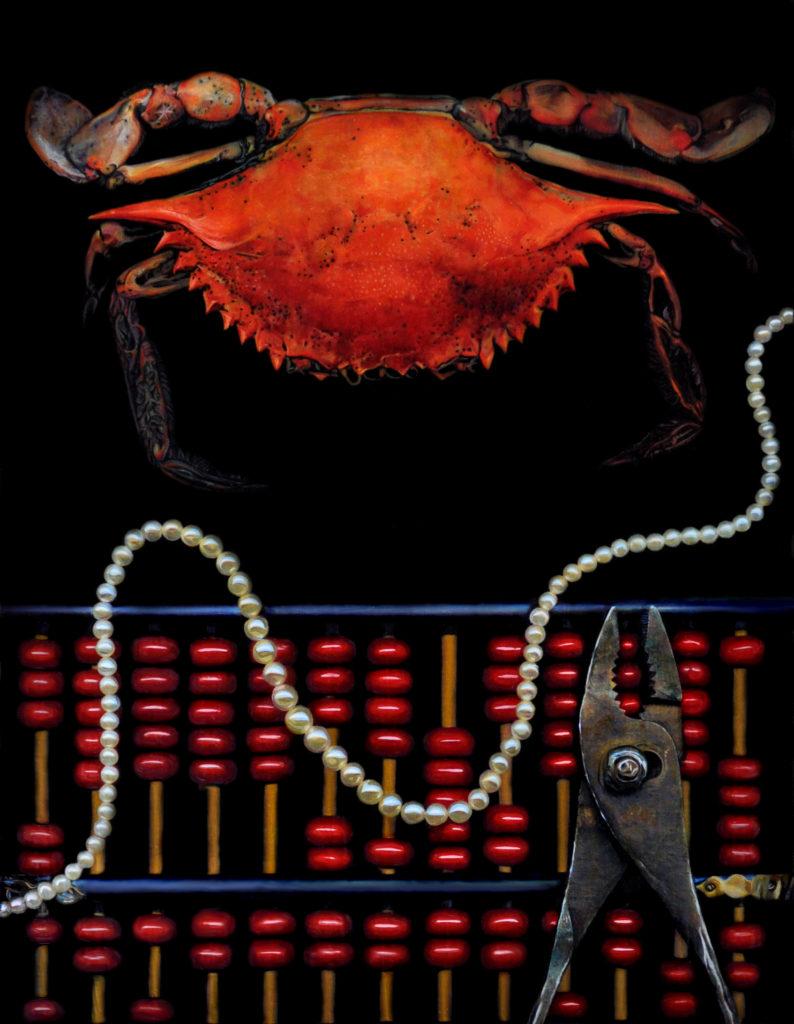

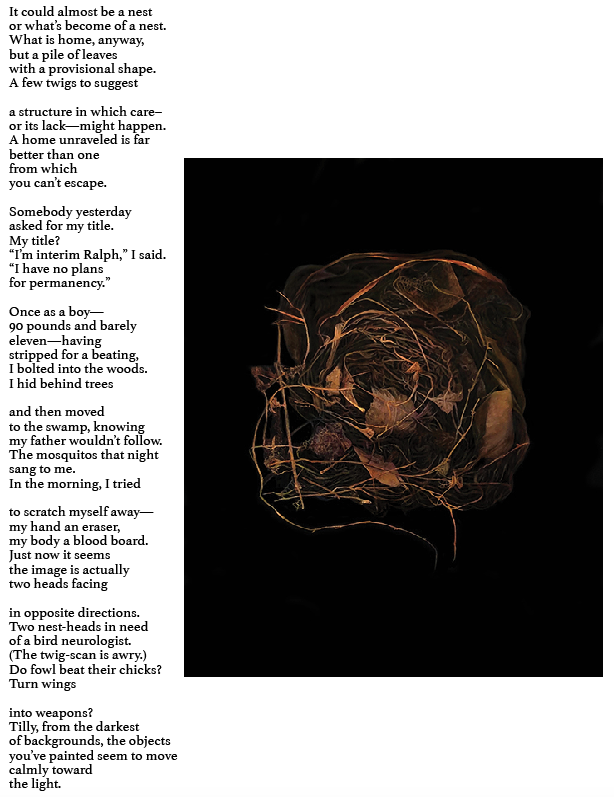

Poem: ABACURSE // Painting: Mixed Metaphor

Savarese: As friends doing this project, we know something about one another’s lives. One of the great things about poetry is that it can refract a narrative. We have some pretty potent objects constellated in this image and I was eager to think about relation in a romantic context and in a commercial one — the cost of things.

Woodward: There’s a reason why I’m a painter. I find words pretty difficult. I find trying to think in a linear fashion sometimes intimidating, sometimes confusing, and there’s something about a painting and the way that meanings can layer together, the way light works, the way colors work, the shapes, the composition and the way that objects are metaphors. There’s this transfer of power in a poem, in a painting. I see the things, interpret the things, but I don’t control your experience, and I don’t control Ralph’s experience. But I hope that there’s enough investment in terms of the quality of the work, the way that things are arranged, that your own meaning begins to come forward and connect somehow with mine.

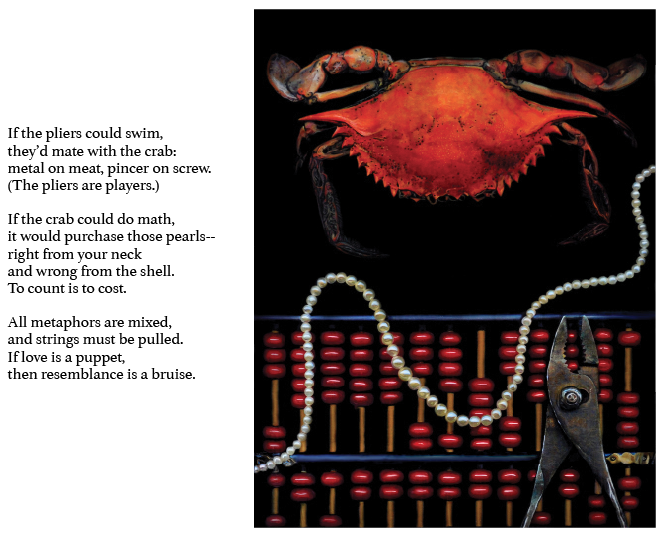

Poem: HIEROGLYPH // Painting: Hummingbird (Presented at event with accompanying video element)

Woodward: One of the things that was interesting to me about working on this project was the transfer of creativity. So early on, I had the easy job because I’d already done the paintings. Ralph’s job was to pick, and then to write in response to the paintings. We decided that we would put together this video which actually was a really wonderful opportunity for me. It’s different than painting but also lovely in that you’re weaving together images, text, there’s music that we use and to get those to work together was a really lovely experience because as a painter, it’s a very still, quiet process. You’re very focused. One stroke follows another and a whole is completed. But working in video, there’s this weaving of time that happens that was pretty lovely for me.

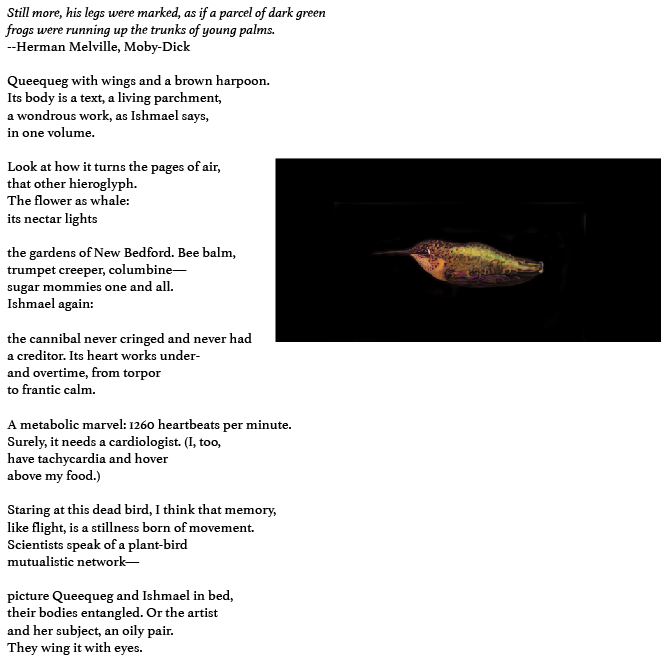

Poem: FAILURE STRAIN // Painting: Rubber Band Balls

Savarese: I remember seeing this painting for the first time on Tilly’s website and I really love rubber bands. It was a perfect occasion for researching the history of the rubber band. This is what people like me do. You may think that I’m not doing anything useful, but I’m going to tell you something about the rubber band and its invention as a way of holding your newspaper together. This strikes me as an essential function of the rubber band.

Part of the pleasure of responding to these paintings was first trying to figure out this strange light that Tilly uses. My only analogy is the afterlife. It feels like her objects have been lit by a light that is much later, after what we’re accustomed to. I had to think about that poor little ball of rubber bands which doesn’t have any color and is sort of less well-lit. That super-intrigued me. The poem comes out of the physics of a rubber band and the point of elasticity. We all know when a rubber band breaks.

Woodward: One of the things that I loved was Ralph’s sense of humor but also how he hid it at the same time. So there’s a darkness and then there’s also a lightness which perhaps carries through in my paintings as well. There is the sense of, for me, coming out of the darkness with these paintings. These are projected much larger than they actually are. The scale is one to one. So the largest of these paintings are maybe 11 by eight and a half-ish. So you’re seeing them projected at a larger rate, but think of the intimacy of something that’s very, very small in that way.

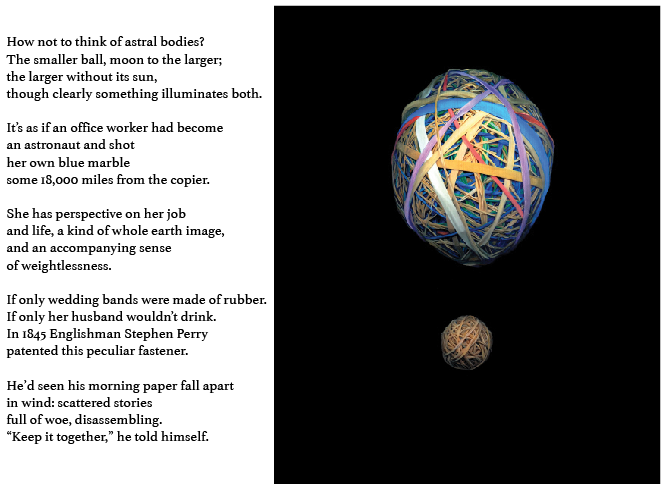

Poem: INTERIM // Painting: Ambiguous

Savarese: I spent hours just looking at this thing. It really, really haunted me, this sort of barebones of suggestion here. I tried to discover for myself what the image was, what it said and again, that very strange Tilly Woodward light, which was spooky in this case at least to me.

Nests for a lot of people are kind of happy, cheery thing. That’s not true. I adopted a child from foster care, who was brutally abused there. So for me, the nest as home starts as an ambiguous thing. So I don’t know why it triggered that memory, of literally fleeing my father. Two things happened. That memory came back, but also the memory of how as an adult, I tried to do something radically different. I adopted my son with a very different sense of what a nest or a home could be.

Woodward: I love to paint nests. It’s never just one thing for me. A nest is a place that’s a home, it’s a womb, it’s a place that you could fledge from. It’s a variety of things. So if you think about it in terms of the structure of the nest, there’s this being with no hands, with a beak and some feet and the way they weave together, small bits, small parts to construct the structure of this poem. In this particular nest that I found — and people bring me nests frequently and dead birds, and insects — I was really struck by the fact that it wasn’t complete and it was hard to tell whether it was being constructed, whether it was falling apart, how that fit in my life, how that represented the passage of time, our passage as humans, the passage of the world. There’s something very quiet about it. So making a poem, making a painting, to me, it’s a really meditative process. It’s a moment where I can really focus in and the world that I find very confusing can go away and for the two hours that I spend painting in the evening after work I can see something clearly in a way that it’s very difficult to make sense of when the world is happening around you. In some ways I think of these paintings as prayer.

Savarese: Tilly begged me to cut those last lines of this poem. She did not want the overt attention, the directed address. So we wrestled at times. For me, that poem, I think about my son’s early life, I think about my own life. I think about the way as adults, we try to sort of correct for what we imagine that early life to be. The image was so evocative, as Tilly said, of something both falling apart and in the process of being built.

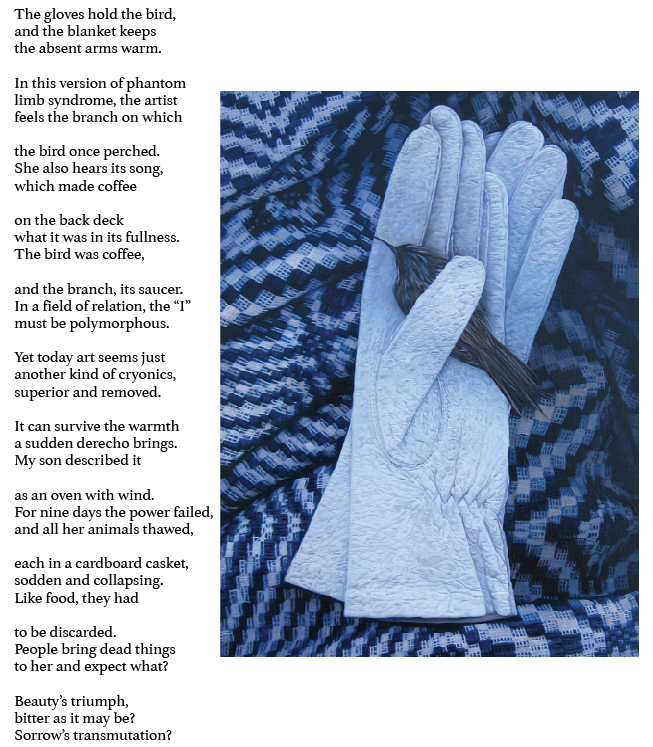

Poem: THAW // Painting: Bird Blanket Gloves (Presented at event with accompanying video element)

Woodward: One of the things that was really hard for me about the derecho was the loss of a freezer full of specimens that people had given to me over the years, so maybe 30 year’s worth of people saying, ‘I found a dead bird, it’s run into a window. I think you’ll want it,’ which is true. One of the things that I feel like I’ve been charged with over time has been this creation of some beauty from a sorrow. I think that’s really evident in the paintings. The way that art can help us process what’s most difficult in life and what’s most painful in life, and then also reconnect us with beauty and help recharge us and refuel us. That’s often the motivation for the work that I do.

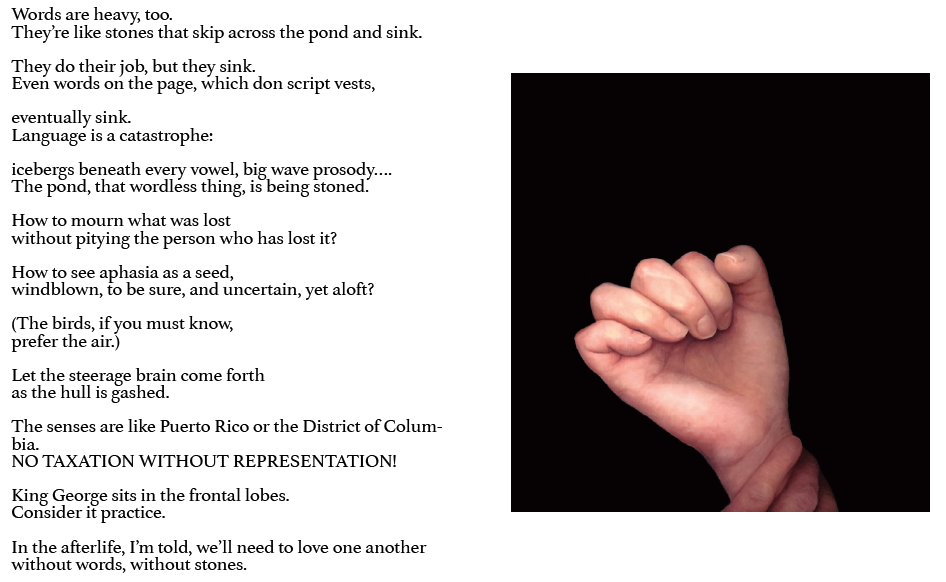

Poem: APHASIA // Painting: Words Are Hard

This piece is dedicated to Professor Astrid Henry, Gender, Women’s, and Sexuality Studies. In 2015, Henry suffered a stroke.

Savarese: All sorts of members of the community work with Astrid and she’s learned to recover language and do all sorts of things. One of the things that is so remarkably poignant for me is Astrid was one of the people in this community who was particularly sensitive to my son. I adopted my son from foster care. He’s a non-speaking autistic person. She was the most natural and affirmative about him and about disability. So, part of what was driving this was a desire to honor that aspect of Astrid but also to shine that light back on her disability.