By Alanis Gonzalez

gonzalez@grinnell.edu

Mental Musings explores mental health from the perspective of a low-income urban Latina woman throughout her 20-year journey with issues such as anxiety and depression. Each week, the column will dive into various topics related to mental health through personal narratives as well as one-on-one interviews.

Adults frequently reference the blissful ignorance of childhood and adolescence. I’ve often heard nostalgia from various adults I knew growing up of how simple life seemed to be as a young person, how carefree their thoughts and worries used to be. Whenever I heard their descriptions of carefree summers and mid-20th century freedoms, I nodded and smiled. “Those are the best years, before everything gets complicated,” they would tell me. I found it confusing, for someone who didn’t look like me or anyone I knew to tell me what the best years of my life would be.

It’s only now that I fully understand why these statements confused me. I can’t remember any significant period where my mind did not worry over obstacles both large and small, all while never allowing me to enjoy the simple joys and full life my family provided me. My flawed programming never allowed me a moments rest, not even as a small child. This issue, on top of the obstacles my family faced as a low income Latinx family, only added to my skepticism concerning what “the best years of my life” would look like.

I had my first panic attack at five years old. Now, I know to some people that may just sound like I had a particularly emotional tantrum, but no. That’s not what it was. The experience has remained so vivid in my mind that only as an adult when I finally have the vocabulary am I able to describe it.

The memory starts in the playground. I went to a small Catholic school on the northside of Chicago with a playground that faces the bustling traffic of Western Ave. My kindergarten class had been let out for recess, and I, along with a few others, played at the side of the playground lot. I can’t quite remember why, but we had begun to mess around with the rocks at the edge of the parking lot, perhaps trying to build something with left over woodchips and other random finds. In our search, I uncovered amid a pile of gravel a thin yellow straw that looked like it had come from a Capri Sun. The straw looked like it had been used and was covered in gravel. My hand immediately felt dirty. “Someone had used that straw,” I thought. “And now, it’s covered in gravel.” The dissonance of the straw and the gravel as well as someone else’s germs on my hand all caused a tightening in my chest. I put it down, trying to ignore the burning I felt on my fingers. They were dirty. Dirt means germs. Germs means getting sick. I need to wash my hands. My kindergarten teacher called us to line up to go back inside.

The dissonance of the straw and the gravel as well as someone else’s germs on my hand all caused a tightening in my chest. I put it down, trying to ignore the burning I felt on my fingers. They were dirty. Dirt means germs. Germs means getting sick. I need to wash my hands.

I tried to keep myself calm, but my chest kept constraining itself, almost like a balloon had landed and stuffed itself between my lungs. We walked into my kindergarten classroom covered in fun seasonal art, colorful calendars and bins of picture books. The teacher instructed us to take our seats and, as I made my way to sit down, I saw it. A bucket of bleach. The janitor must have come in to clean the floors. I still needed to wash my hands. But what if I couldn’t go? What if my teacher wouldn’t let me and made me wait? All that was there to clean my hands was bleach and bleach was bad for you. Gran had told me so. My fingers still burned where I had touched the straw and I began to feel trapped. Within minutes I was in tears, unable to explain myself.

My teacher, confused by my hysterics, sent me to the front office where the secretaries double as nurses and attempted to calm me down. They laid me on the nurse’s table. The pictures of little sick faces with thermometers in their mouths proceeded to scare me further and my sobs only worsened. “Honey calm down, it’s okay, it’s okay,” they comforted me. “I think it’s about her mom,” they whispered to each other. Had I been able to speak, or had they asked, I would have said no. No, my hands are burning with someone else’s germs. But they insisted, “Honey it’s okay, you just miss your mom.” Eventually, as they were unable to appease me, they called my aunt and I was sent home. For years after this event occurred, I struggled to understand why the secretaries had insisted that I missed my mom. I now, however, understand their skewed and biased reasoning.

My mom had me at 19 years old. Not only was she young, but she came from a low-income immigrant household, with my grandma having worked as a cleaning lady for most of her life. As the American–born child, she had navigated the United States for the first time with her parents all throughout her childhood. She has acted as the family matriarch, taking care of everyone, including her parents, from a very young age. When I was a young child, my mom worked three jobs just to make sure that I could go to my little Catholic school while also paying the rent for our apartment. Remember that when I was five, she was 24. Imagine yourself, two or three years from now, give or take, taking care of a five-year-old. She’s the strongest person I know.

And yet, the teachers and mothers at my school were not satisfied. They assumed her absence, along with my grandma’s active role in my education, to indicate my mother’s inability to take care of me. All they saw when they looked at all of us was a poor, Mexican family. And so, when I showed any emotional issues as a child, from that day forward, it was always disregarded as neglect. A failure on my mother and grandmother’s part to raise me. From that day forward, I was too emotional, too impulsive and I obviously was not being taught how to control my emotions. Their treatment of my family throughout my time at the school that shall remain nameless does not merit documentation. All that need be said is that it was subtly racist and classist, all delivered with smiles.

Their treatment of my family throughout my time at the school that shall remain nameless does not merit documentation. All that need be said is that it was subtly racist and classist, all delivered with smiles.

What they didn’t realize is that my mom and grandma gave me a beautiful life. Even though we had our fair share of financial struggles, I knew, every day, despite how many worries flew around my brain, that I was loved and wanted. It’s also worth mentioning that in my worst moments, on the days when I was still too young to understand why they called me emotional and impulsive, my mom and grandma never made me feel ashamed for who I was.

The language used to describe me contains racial connotations behind the perception of women of color. In fact, I think the treatment I received as a child as well as an adolescent because of the racial stereotypes imposed on me exacerbated my anxiety. An article on Medical News Today emphasizes this, stating that prejudice not only worsens conditions such as anxiety, but also effects the treatment that people of color receive from medical health professionals.

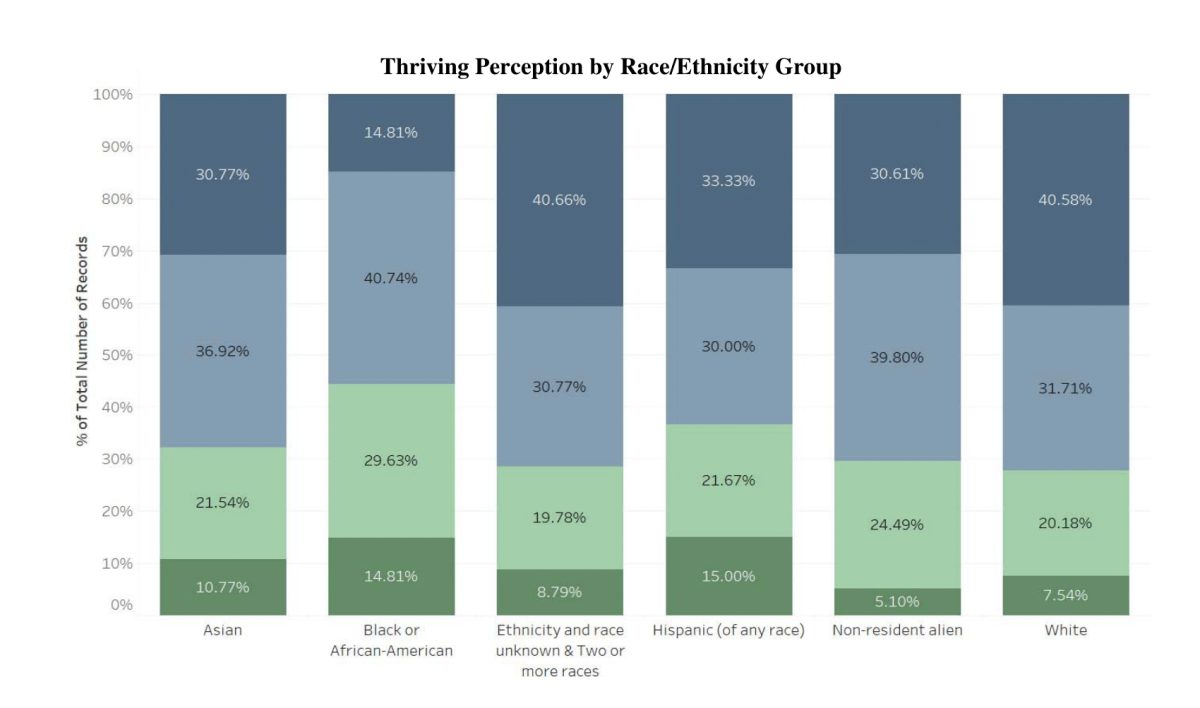

Additionally, the article highlights the inaccessibility of mental health resources. Only 30.6 percent of Black people and 32.6 percent of Latinx people received treatment for their mental health in 2017. This differed greatly from the 48 percent of white people. These statistics speak holistically to the obstacles behind gaining access to mental health resources in the United States, as well as the additional systematic barriers placed in front of Black and Brown communities. These aspects do not even begin to touch the surface and also do not account for intersectional identities that overlap with aspects of gender and sexuality.

Only 30.6 percent of Black people and 32.6 percent of Latinx people received treatment for their mental health in 2017. This differed greatly from the 48 percent of white people.

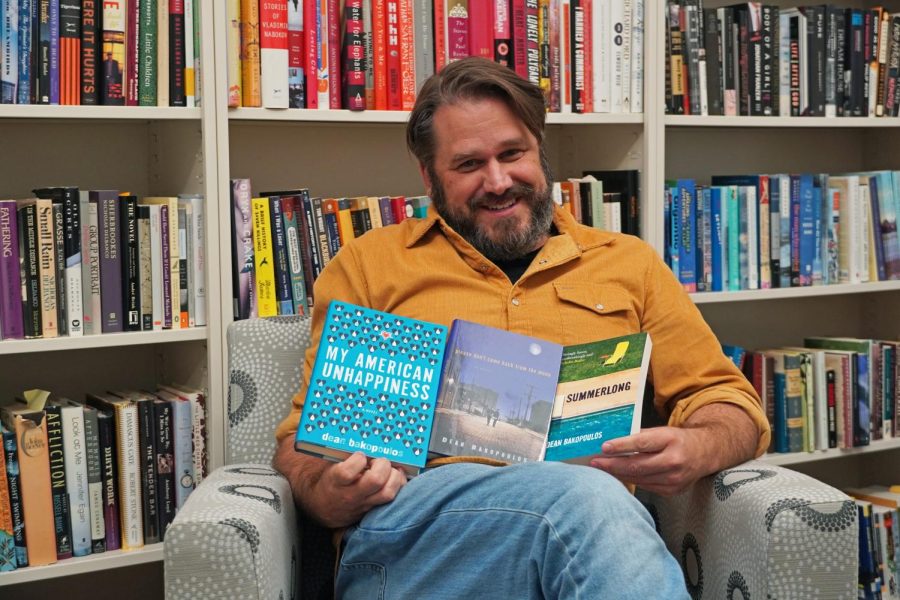

An Instagram page hosted by Dr. Jennifer Mullan (@decolonizingtherapy) has been a personal guide to me as I’ve sought to learn more about the bias in the mental health field. Dr. Mullan crafts posts with phrases such as “rage simply wants to be seen,” and “We decolonize our therapy in order to take back our land, or cultures, or lives and our ancestral healing.” The page addresses issues such as ancestral trauma and healing, the effects of the capitalist mindset on communities of color. It’s pages like this that have allowed me to relearn everything I thought I knew about myself and my mind. I am not crazy, nor am I over emotional: I’m just Alanis.

When I hear adults glorify their childhood and teen years, I smile and I still agree. Especially in the last year, I miss my spontaneous adventures on the train and running around the church garden with my middle school friends. Still, I don’t see it with the rose-colored lenses that many, mainly white, people view their childhoods with. I was still born into a world that would never accept me for who I was and continuously used my Achilles’ heel against me. More importantly, I still felt these rushes of panic and an overwhelming sadness, and I didn’t have the resources or even the vocabulary to describe what went on in my mind. And so, although I can agree with some elements of their nostalgia, I have found more refuge in my adulthood, when I have learned word such as “intersectionality” and “inaccessibility.”

Ignorance is not always bliss. Sometimes, it is a detriment.

Any opinions expressed through columns and other S&B opinions publications belong to the writer and do not reflect the views of any or all members of The S&B staff, nor by any Grinnell associated organization.