Quick Cold Cases is a biweekly column in which various S&B staff members briefly dive into cold cases from across the globe. Each writer will provide a brief summary of the case before using their best investigative skills to describe what they believe happened.

The pictures are out there on the internet, though I don’t recommend going looking for them. Her skin is charred black and gray, the sole of one foot shockingly white. Her head is thrown back, her right arm crossed across her chest and her left arm slightly raised.

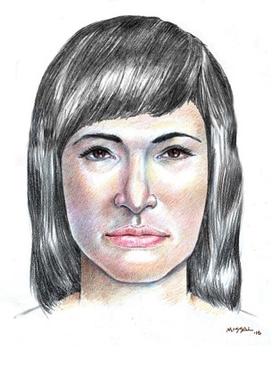

This is the Isdal Woman, named for the valley in Norway where she was found, nestled between rocks, on Nov. 29, 1971. Near the body, the police found jewelry, a watch, a broken umbrella, a pair of rubber boots, a few plastic bottles of water and some paper, illegible from the fire. The tags had been torn out of her expensive clothing, the labels scratched off the bottles. Her real identity is still unknown. She certainly wasn’t a local, as no one in town knew her and no women matching her description had been reported missing.

Her body also gave evidence of how she’d died. There was soot in her lungs, meaning that she’d still been breathing when the fire started. Her cause of death was listed on the autopsy report as a combination of carbon monoxide poisoning from fire and the 50-70 barbiturate sleeping pills in her stomach. Three weeks after her body was found, the Norwegian police released their verdict: suicide.

Isdal Valley, an hour or so hike from the nearby city of Bergen, doesn’t make much sense as a place for a suicide, especially for someone unfamiliar with the area. It also doesn’t make sense that a tourist would pick cold, dark late November as the time to visit.

I think she was a spy. The police found two suitcases that had been left in the Bergen train station on Nov. 23, six days before her body was found. The suitcases contained, among other things, a notebook written in code, wigs, glasses with no prescription, cosmetics, and more expensive clothing, all with the labels torn out. The elements of disguise. A fingerprint on the lens of one of the glasses matched the body, so we know these suitcases were hers.

Her luggage also contained a plastic bag from a shoe shop in Stavanger, Norway. An employee at that shoe shop recognized the rubber boots that’d been found with the body; he’d sold them to a rather memorable woman. She wasn’t Norwegian, he said (in 1971 very few foreigners lived in Norway), and she spoke English with an accent. She smelled bad, strongly, like garlic, and she spent a long time deciding whether or not to buy the boots and ended up coming back to buy them the next day. There was a gap between her front teeth when she smiled.

The suitcases contained, among other things, a notebook written in code, wigs, glasses with no prescription, cosmetics, and more expensive clothing, all with the labels torn out. The elements of disguise.

Based on that description the police tracked her back to a hotel near the shoe shop, where she signed in under the name Finella Lorck, claiming to be Belgian. But of course, the Belgian police said they’d never heard of any Finella Lorck, and the passport number she’d given the hotel was fake. A woman of the same description had signed in at other hotels around Norway, with the same very distinctive handwriting, under at least seven different names.

What would a spy be doing in these two cities? Stavanger, the city where she bought the rubber boots, is the offshore oil-drilling capital of Norway, where all the oil execs hang out. And in 1971, amid the Cold War, Bergen was home to the largest naval base in Norway, with NATO military exercises taking place in the harbor.

Mitochondrial DNA testing did ID her as being from Europe, but her DNA didn’t match with anyone in the Interpol database, and it hasn’t been compared with any commercial databases. Commercial databases are somewhat reluctant to share their data with the police, because they don’t want their customers getting arrested if they’re connected to a crime that way. Of course, police in the United States have used commercial databases and genetic genealogy (identifying people through their distant relatives) to solve cases such as the Golden State Killer, and Norway might follow suit soon.

There was a gap between her front teeth when she smiled.

The other way modern technology could identify her was by her teeth: she had very distinctive gold crowns, the kind of dental work that was done much more in Germany and Eastern Europe than Scandinavia. Isotope analysis of the teeth can also tell you where someone was living when they were young, because different areas have different fractions of isotopes, and the Isdal woman spent her young childhood in Germany – specifically the Nuremberg area – but moved fairly early in life to somewhere else in Europe.

You can also determine the age of biological materials by analyzing the amount of radioactive 14C, which decays at a predictable rate into 12C after death. Carbon dating told us she was born in about 1930, and a child who fled Nuremberg in the late 1930s may well have been Jewish. If she lost her family during the war, that might also result in her not being reported missing.

As to who she was spying for and why she was killed, I can’t do more than guess. Israel was doing espionage in Europe at that time, as well as far-left political groups not associated with a particular state. She probably wasn’t working for the Soviets, because according to former Soviet spies, seven alternate identities were far too many. Soviet spies only had one. She might have been killed by someone who found out she was a spy (but why wouldn’t they report it to the Norwegian government? Maybe because they were ashamed of information they’d already given her?) or she might have tried to quit and been killed by her own organization.

Someone knows who she is. Whoever was financing her expensive clothing, false passports, and hotel-hopping lifestyle knows her real name. Tell us. It’s been 50 years.

Any opinions expressed through columns and other S&B opinions publications belong to the writer and do not reflect the views of any or all members of the S&B staff, nor by any Grinnell associated organization.