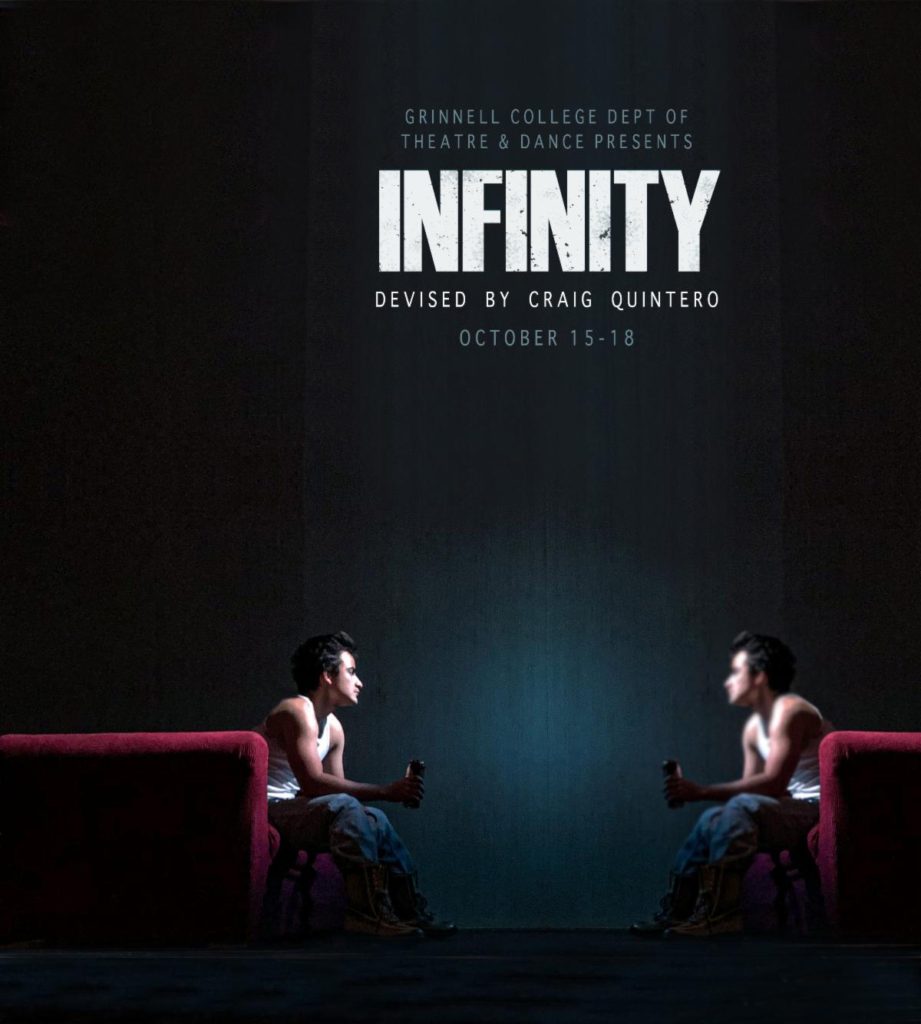

In a semester filled with new and unusual firsts, Grinnell College’s first mainstage production of the 2020-21 school year was no exception. Instead of collecting a ticket at the Bucksbaum box office and filing into seats in Roberts Theatre, eager audience members logged onto YouTube for the live-streamed production of “INFINITY,” starring Isidro Mendizabal ’23, Lilith Hafner ’23, Reese Hill ’24, Kelly Banfield ’24 and Mira Berkson ’20.

The student performers are all enrolled in THD 195 – Online Performance, taught by Craig Quintero, marking the first time a mainstage production has counted as a full four-credit course. After Grinnell switched to remote learning for F1, the Theatre and Dance Department needed to rethink how they could bring theatre to the main stage in the new world of social distancing.

“Instead of trying to back away or resist the challenges of online performance, it was like, ‘Well how do we embrace this medium?’” said Quintero, who was slotted to direct the first mainstage production of the 2020-21 school year.

Rather than start with a script, as a more traditional theatre production would, Quintero relied instead on the creativity of his students to develop the performance in a collaborative setting. Due to the nature of the remote course, each student was more than just an actor; they adjusted lighting, painted sets and operated the camera from the stages they created in their homes. While the students took on many roles traditionally held by a tech crew, they were aided throughout the process by technical director Erik Sanning, assistant technical director Kate Baumgartner ’15 and costume designer Erin Howell-Gritsch.

Many of the scenes performed in the final production were experimental pieces developed by students throughout the course.

“I made a scene,” said Mendizabal, “[for] one of the classes, in which I was just in my bed and there was some noise that I couldn’t understand where it came from. And you could just barely see my feet, and then the camera slowly moved down, and there was something below my bed.”

This eerie scene was recreated in “INFINITY” using a camera positioned under a desk looking out at a darkened room lit only by a flickering TV. With the camera capturing Mendizabal’s silent form as he moves across the room unaware of his audience, viewers are left with the dawning impression that they could be the very monster under the bed Mendizabal described.

Mendizabal is living on campus, so he was able to record his scene on stage in the Roberts Theatre, but for other students living off campus, it was a bit trickier to create that theatrical space.

Reese Hill ’24, who is currently living in Iowa City, performed her scenes in her bedroom using props she had on hand and at one point, in a scene where red flower petals fell from above onto her hands below, with the off-screen assistance of her younger brother.

The production’s scenes shifted smoothly from one to the other, often signaled by the camera’s movement through a wall or in one case through the floor and several inches of dirt. To achieve these transitions, Baumgartner and Sanning developed a pulley system that the actors then copied. The system utilized a cart where each actor could attach their camera phone and pull it down a trolley track to record the vertical or horizontal movement. In one instance, in order to be both in front of and behind the camera, Berkson worked the pulley with her foot.

While the socially distanced production was forced to go digital, the essence of live action so unique to theatre was maintained in that all but a few scenes were performed in real time. As Mendizabal’s scene was staged in Roberts Theatre and required Baumgartner to operate the camera, it was one of the few scenes pre-recorded for the production.

The other recorded scene was devised by Lilith Hafner ’23, a gripping sequence of layered videos shifting from a stricken face to a dark earthen hole shot from above with disembodied hands mixing dirt into mud, a process which takes up enough time to become uncomfortable, forcing the audience to question whether the mud itself is a story being told. But before a satisfactory answer is given, another layer is added and the hands begin to play in space with a program’s control panel, alluding to a manipulation of the natural and digital worlds. The scene required some technically tricky screen recording that unfortunately was too much for Hafner’s internet connection and could not feasibly be streamed live.

In order to broadcast the live performances, Sanning used a program called Wirecast. Intended originally for use in a TV studio, Sanning and Baumgartner were able to tweak the software to operate the live streams from multiple phone and computer cameras capturing performances from each of the actor’s locations across the country. During the live production, Sanning manned Wirecast from campus while Baumgartner managed the actors using a sequence of visual cues to notify them when their cameras were live.

In discussion with The S&B after the opening performance on Thursday, Hill shared how this performance was similar to the traditional theatre productions she was a part of in high school. “Before opening performance today, I was really nervous, like the same feeling backstage of ‘Oh what if I pop out of the wings too early?’ Or ‘What if something goes wrong and they see something that they’re not supposed to?’ ‘What if I mess up my lines?’ even though I don’t say anything on stage in the show.”

Hill noted that these anxieties, however, are the only similarity between her current and past performances. “INFINITY” is an abstract work, not meant to have a plot in the way of traditional scripts. To Mendizabal, “INFINITY” is unique to every person who watches it and calls for an emotional response rather than an intellectual one. “Grinnell, because it’s an academic place, treats anything related to art as just trying to analyze it, [asking] ‘what does it mean?’ and trying to make an intellectual conversation around it.”

Quintero shared a similar sentiment, saying “Theatre has this ability to serve as a reflective medium to see oneself, to know oneself. And so, in the performance … it’s more about creating this series of moving images or living sculptures, where it becomes this reflective surface or this meditative space where the audience, through seeing this, somehow taps into their more subconscious feelings and emotions.”

A recording of the production can be found on YouTube.