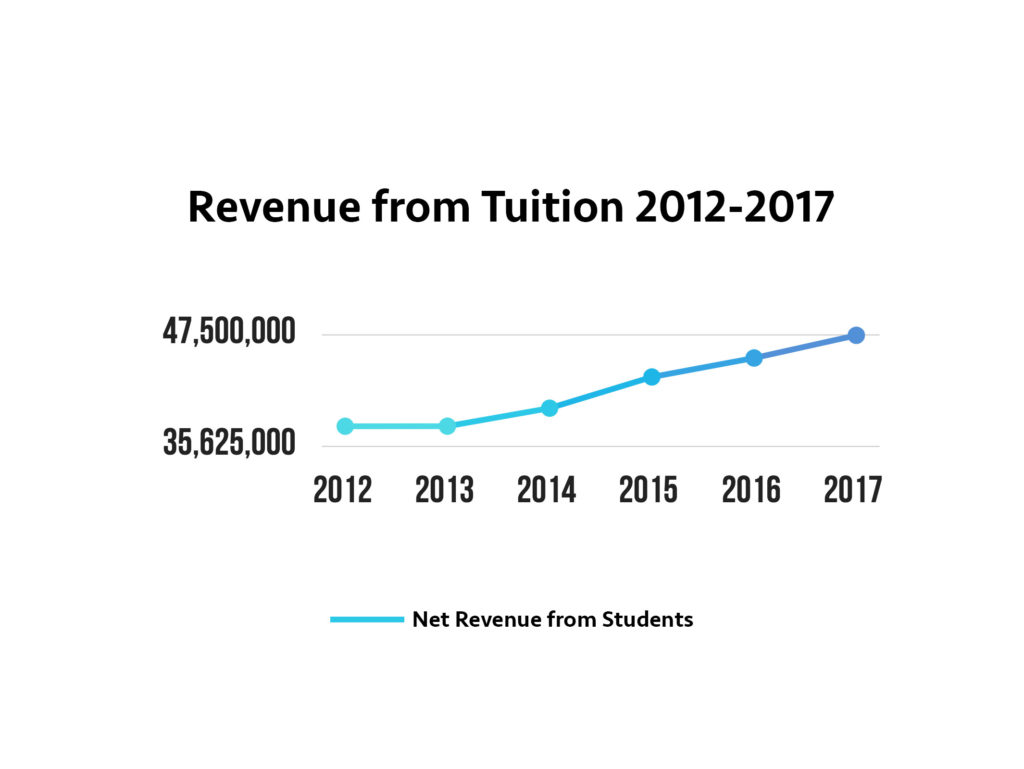

As tuition prices soar nationally and college students anticipate an increasing burden of post-grad debt, Grinnell College remains one of a few institutions retaining the policy of need-blind admissions and meeting 100 percent of demonstrated need for admitted students. The College, however, has increased tuition dramatically over the past five years, netting $9.6 million more in tuition from 2012 to 2017.

So how does the school make increasing revenue on student tuition while remaining need-blind? The school has a few ways of pulling high “student revenue” while maintaining a policy of not considering student’s financial need in admissions.

For one, not all applicants are treated as need-blind applicants: students applying from abroad and students from the United States but without legal citizenship are required to apply as “international students” and are subject to a “need-aware” evaluation. According to the College’s website, “[t]he College requires a clear and honest submission of family financial resources to determine an applicant’s aid eligibility” from international applicants.

For domestic students, the College does what most organizations with money to spend on advertising do: buy and interpret information about potential customers from other companies.

“We do purchase names off the College Board through ACT — I’m sure you remember when you took the exam you started getting all this mail from colleges and universities, and of course we engage in that practice as well,” said Director of Admissions Sarah Fischer.

The College incorporates available data on high school students around the country to gauge interest in the school and focus recruitment on a diverse and high-achieving group of students who have expressed interest in the College. Fischer emphasized that revenue is only one of the school’s goals in recruitment.

“Building this deep pool of diversely qualified applicants through our recruitment efforts … allows the admission committee to select a pool of highly qualified students without regard to financial circumstances while still moving towards the revenue objectives set forth by the college. We are proud to consistently enroll a class that brings in a broad range of backgrounds and perspectives, including socioeconomic diversity across geographies,” Fischer wrote in an email to The S&B.

The College sorts and interprets data on prospective students using Slate Technolutions, a service that, according to the company’s webpage, over 650 colleges and universities use to keep track of their student and admissions data. Among other functions, the Slate database stores prospective students’ test scores, home addresses and the number of times they’ve clicked on the College’s admissions webpage.

This does not mean that the College can gauge to a dime the amount of tuition its prospective students can provide as the College does not require from applicants their Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) information or any other explicit financial records.

“The best indicator that we would have of a student’s financial background would be where they live, and that’s a flawed analysis. Because people who live in California, for example, with incredibly inflated home prices could live in a zip code that’s got million dollar houses, and that [might not be] actually indicative of wealth that that family has … It’s an incomplete analysis,” Fischer said.

Furthermore, data indicating a student’s financial status is used to reach a wider pool of applicants and has no sway on the process of admitting students.

“You can make inferences [about financial status] based on zip codes, but that’s very separate from the need-blind admission process. So, we don’t take any of that information into account when we’re making our admissions decisions,” Fischer said.

In agreeing to meet both full need and admit students without considering their finances during admissions, the College exposes itself to the risk of unpredictable student revenue — tuition — for its operating budget. The College’s most recent Fiscal Year budget report shows that between 2007 and 2017, the school saw its costs rise by 5.44 percent and experienced a 4.96 percent increase in revenue. The increasing revenue reflects both a steady increase in tuition and returns on the College’s endowment, while the costs represent, in part, College construction projects such as the Humanities and Social Sciences Complex (HSSC).

While for now, the College uses relatively little personal information to understand its applicant pool and recruit accordingly, the acquisition and trade of data represents a brave new world for not only credit agencies but, apparently, college admissions as well.