Michael Cummings, Community Editor

cummings@grinnell.edu

Human trafficking—the illegal buying and selling of people, usually into sexual slavery or forced labor—is a pervasive and oft-ignored issue. It is a problem all around the world, even right here in Iowa.

On Tuesday, March 1, Dan Werner ’91, Senior Supervising Attorney at the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) gave a talk in JRC 101 to educate the Grinnell community about a specific case he fought against human trafficking.

Werner was introduced by his friend and Grinnell Professor Doug Hess ’91, Political Science, who quipped about the trouble they got into together during their time as students here.

“I will avoid discussing more about what Dan and I engaged in while students because there’s still some statute of limitations issues at play, but we may have spent at least one night in jail,” Hess joked.

Turning to a more serious note, Werner took over the microphone and began his presentation, centering around a lawsuit which he worked on for most of his first seven and a half years of his time at the SPLC.

The case was against Signal International, a marine construction firm based on the Gulf Coast, which saw Hurricane Katrina as a big opportunity to make a profit.

In great need of new workers, Signal contracted out employment to three people, referred to affectionately by the SPLC as the “Axis of Evil,” who promised to bring in cheap labor from India.

“The Axis of Evil made this offer to Signal. It was awesome! … ‘he could provide us first-class fitters and welders and deliver them to us at no cost to Signal,’” Werner said, quoting testimony from a Signal Vice President.

The “Axis of Evil” brought 500 Indian laborers to America on the promise of Permanent Residence cards, getting them to take out loans to pay roughly 10,000 to 20,000 dollars each for these visas. The visas, however, were not Permanent Residence cards, but rather were specific work visas which bound workers to the company that sponsored them.

Once in America, Werner explained, the laborers were forced to live in cramped, squalid conditions. Emails uncovered during the trial found that their pay was docked 1,000 dollars per month so that Signal could make a profit off of it.

Eventually, the workers made contact with the SPLC, who brought a human trafficking suit against Signal. Werner explained that the biggest uphill battle he and the legal team faced was breaking down common perceptions of what human trafficking actually is.

“About five or six month before the trial, we did what’s called a mock jury exercise,” Werner said. “You hire people off the streets from the same jury pool to sit and watch your presentation of your case.”

The results of the exercise were grim for the SPLC.

“Two of the three juries … decided that there was not human trafficking,” Werner said. “The person who played the role of the foreperson on one of the panels said something that was really striking and really an important lesson for all of us.”

“He said, ‘I’ve seen “Taken.” This is not human trafficking,’” Werner said.

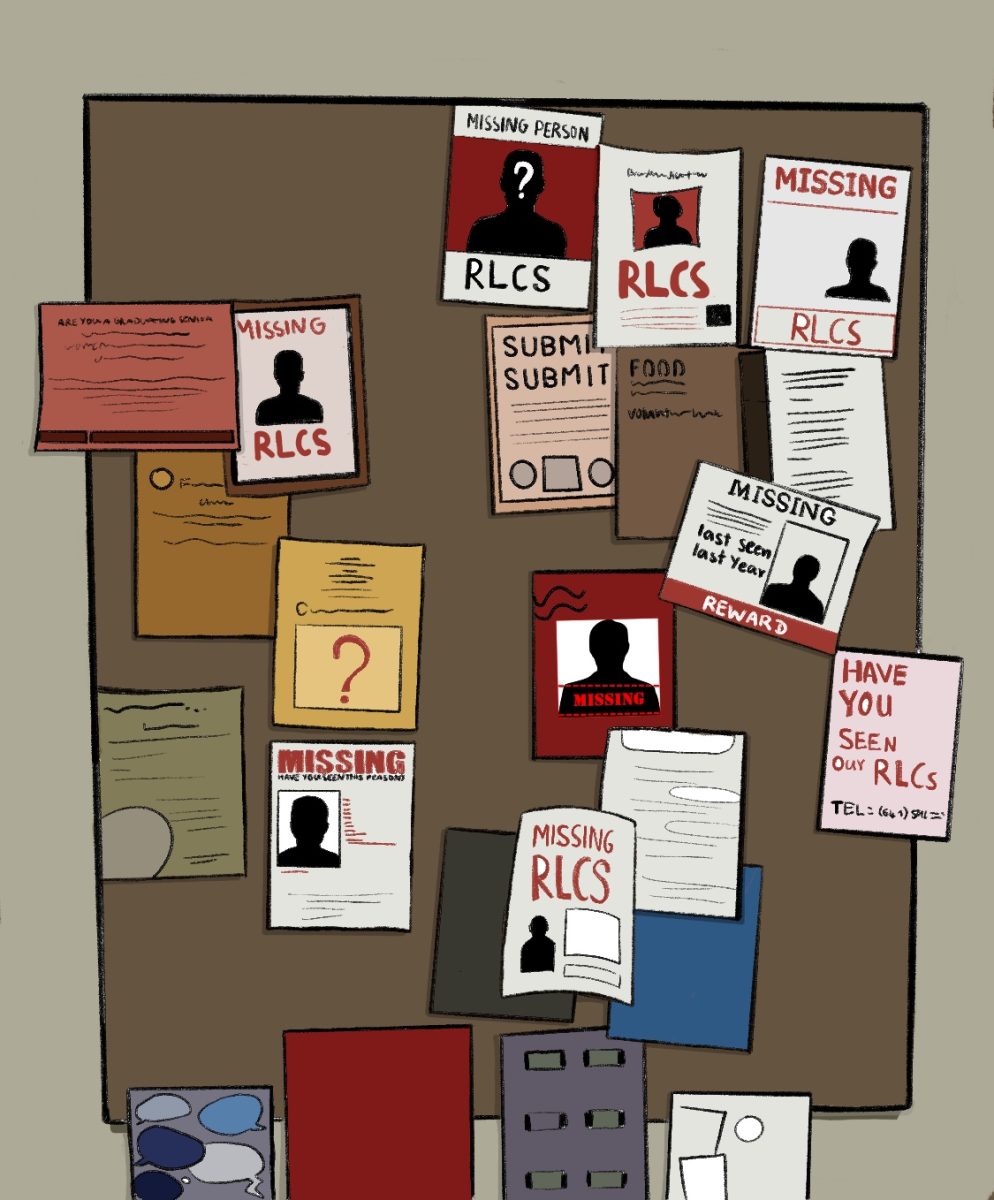

To advance this point about the common perception of human trafficking versus what human trafficking actually looks like, Werner compared pictures that show up on a Google Image search of “human trafficking” to an actual study conducted by the Urban Institute.

He found that on Google Images, 79.2 percent of images depict women and 2.8 percent depict men. The Urban Institute study found that the gender divide is actually roughly 50/50. 61.9 percent of Google images show white victims, while in reality 96.1 percent of victims are of non-European origin.

Werner and the SPLC took this lesson to heart and eventually won the lawsuit, with the judge awarding a significant monetary sum to the Indian victims.

“And it’s a really really really awesome hope story … they actually succeeded and the company that did that, that thought they could get away with it, went out of business,” said Dani Tiedemann ‘19, who attended the talk. “I love going to talks like this because I can see other Grinnellians doing awesome things after they graduate.”

Professor Sarah Purcell ’92, History, echoed Tiedemann’s statements.

“[W]e can see how Grinnell alums achieve great things, and how someone who was a campus activist in his time here has converted that into a career where he is still impacting lives on a mass scale by using the law,” Purcell said. “What we hope is that students will get a chance to envision different pathways for future work.”