Kelly Pyzik, Editor-in-Chief & Eva Lilienfeld, News Editor

pyzikkel@grinnell.edu & lilienfe17@grinnell.edu

When the trustees go behind the closed doors of JRC 101 and decide tuition for next year, who knows what happens? The S&B staff got the chance to look behind the curtain and learn how the college earns and spends its money. Feel strongly about the purchase of the golf course? Wondering why we can’t just use one million dollars to recruit a psychiatrist for campus? Read on and you’ll understand some of the nuances of the college’s financial state.

What is the operating budget?

The yearly operating budget is the bulk of the financial resources that allow the college to run. There is a revenue side and an expense side to the operating budget and they have to balance with one another to allow for responsible spending and proper planning.

According to Vice President for Finance and Treasurer of the College Kate Walker, the revenue side includes a contribution from the endowment, the amount we anticipate from gifts and net revenue from students. The expense side is mainly comprised of three large components: (1) compensation and benefits to faculty, staff and student employment; (2) programming; and (3) investments in small projects to maintain facilities and meet debt obligations.

The expense budget must break even with the revenue target.

“I’m always conservative with the revenue target and I’m always realistic about our budgeted expenses,” Walker said.

For the past three years, we’ve had small to moderate surpluses at the end of the year.

“It says we’re doing the right things,” Walker said.

The surplus goes into a fund that functions as a risk-mitigating reserve for the operating budget if we have a year at the end of which there is a deficit, or a negative difference, between our spending and our revenue.

The Board of Trustees has the ultimate decision on the revenue side of the operating budget, and that choice determines how much money can be spent in the operating budget.

Clint Korver ’89, head of the Board of Trustees, frequently faces these trade-offs in negotiating how much of Grinnell’s 1.8 billion dollars should be allocated to the yearly operating budget.

“If we just [allowed] five percent instead of four percent [for the operating budget], that’s $18 million more. That’s 15 percent of the entire budget. You could have whole new programs,” Korver said. “So then the question is why don’t we do that because you could do so much with that? In order to make that decision, you have to say, ‘What does the whole financial picture look like? What does the endowment future look like? What [do] the returns look like?’”

The budget planning committee includes staff, faculty and student members and meets for 90 minutes every other week from November until late March or early April. The committee takes the boundaries for the year’s expenses based on the Board’s decision about revenue and begins the process of carving out the expense budget for all that it covers.

What is involved in creating the expense budget?

Programming allocations is one of the most difficult parts of Grinnell College financial decision-making because it is very reflective of the college’s values and a lot of qualitative thought must be put into the decisions.

“When we look at programs, that’s where the biggest questions are because where we put our program dollars is a reflection of our mission and our strategic priorities,” Walker said. “We first take a look at how the dollar placements match up against mission, against the six strategic initiatives [and] the cross cutting themes that are part of our strategic plan.”

The six strategic initiatives are the qualitative priorities that guide much of the college’s decision-making and follow the journey of a Grinnell student from the time they are considering attending Grinnell to their after-graduation employment and philanthropic contributions as an alumnus. The cross-cutting themes of strategic importance are two priorities that President Raynard Kington sets out every year. The themes carry across a two-year period, usually taking one year of research into the topic and one year of creating and implementing new initiatives and programming. Last year one of the themes was “Global Grinnell.”

Programming dollars are allocated to things like dues to memberships and associations of which the college is a part, travel expenses for course-embedded trips, the cost of outside consultants and outside speakers which visit to expand learning beyond department curricula. Enterprise risks must also be taken into account with expenses.

“Those are things like hazards, compliance, risks to reputation. Much bigger, higher level kinds of things,” Walker said. “It may be that something that does get funded doesn’t resonate really strongly with one of the other strategic objectives but we have to do it because the government says we have to do it. It’s a compliance issue—it will get funded because it has to be done.”

Title IX is one of these compliances. According to Walker, we have invested a lot of program dollars in Title IX-related services.

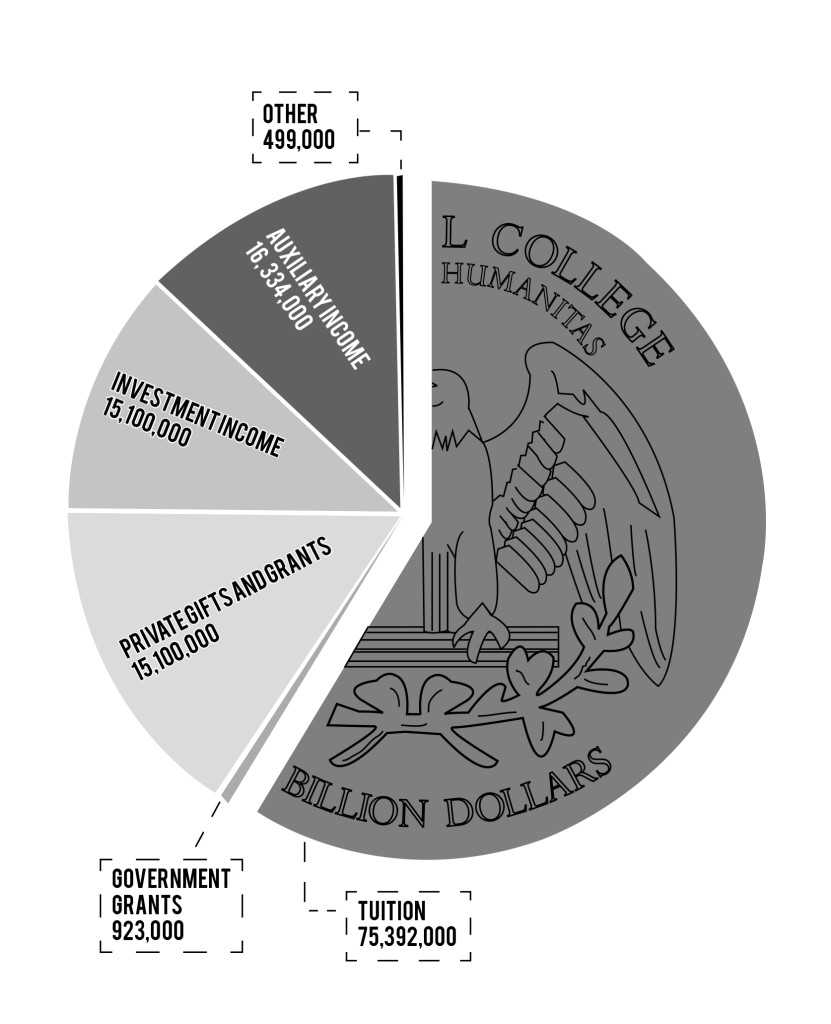

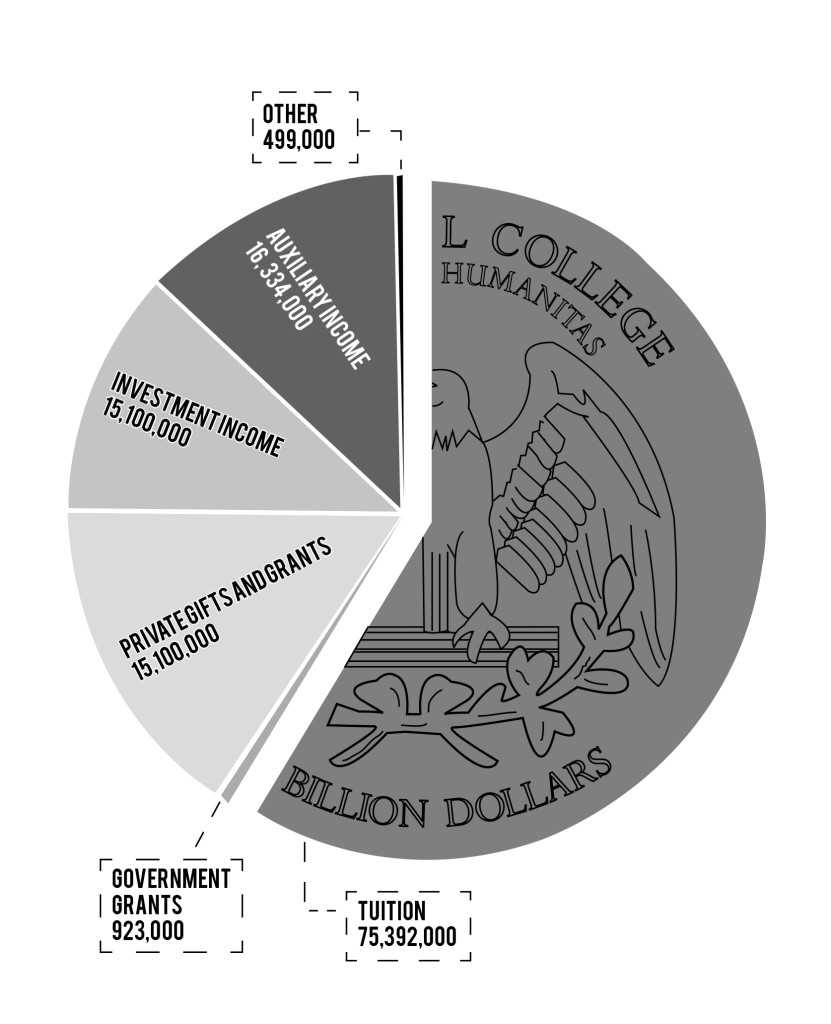

Where does the college’s income come from?

In an effort to balance this operating budget, the college depends on bringing in a certain amount of money. Some of this comes from interest and investment of the endowment, but a substantial portion also comes from tuition and alumni donations.

Though Grinnell’s endowment per student ratio is much larger than those of peer institutions because schools with comparable endowments typically have larger student bodies, Grinnell struggles to bring in necessary funds. While other schools have lower endowments, they bring in large sums of money in alumni donations—money Grinnell has found challenging to generate.

According to Vice President of Development and Alumni Relations Shane Jacobson, the percentage of alumni who give is 38.8 percent, as of last year. This is up six percent from the year before, suggesting that alumni donations may be on the rise. Further, the college plans to implement an eight-year campaign to solicit donations from alumni, the first of its kind in twenty years.

What is a donation campaign?

“Campaigns create an opportunity to shine a spotlight on initiatives that aren’t connected to any one year, they’re longer term goals,” Jacobson said. “A campaign, typically, at many institutions, will encourage more donors and encourage donors to potentially give at higher levels.”

Though the college has not had a formal donations campaign in two decades, Jacobson remains optimistic that the college will be able to enhance the giving program.

What does the Board of Trustees do?

The Board of Trustees includes two committees that handle the college’s finances. The Budget Committee determines the college’s spending for the following year, while the Investment Committee focuses on growing the endowment to benefit the college in the long-term.

Korver has been involved with the Investment Committee, which talks once per month and meets once per year to review the entire portfolio. The investment committee recruits alumni to the Board who have extensive expertise in a particular area missing from the investment committee.

“The investment committee probably has some of the most specialized expertise of any of the committees,” Korver said. “And in fact, when we recruit trustees, we’ll a lot of times consciously think about the public equities person [who] is about to ready to term off, so we need to go find somebody else with that expertise. But it’s not like you can spend a couple of years investing stocks and get public equities expertise. We’re looking for someone who spent twenty years.”

One of the committee’s responsibilities is to determine the investment and endowment’s financial goals, which are then passed along to Chief Investment Officer Scott Wilson ’98. Wilson’s staff then examines potential investments and returns to the Board for approval. The Board gets a final decision in every investment in the college’s portfolio.

“Our investment policy states that the mandate is to maintain the long-term growth versus maximizing annual income,” Wilson said. “We take the very long-term strategic growth and our goal is to enhance the real purchasing power of the endowment.”

What is real purchasing power?

The real purchasing power of the endowment refers to the endowment’s value given that inflation rises a certain amount each year. As inflation rises, the value of a given dollar decreases that amount each year. This is why a quarter used to be able to purchase a bottle of coke. Since those times, the quarter has decreased in purchasing power. This means that the purchasing power of the endowment naturally decreases even if the number of dollars stays the same.

Many investors engage in a process of diversification of investments. This means that they break a billion dollar endowment into hundreds of smaller sums of money and invest them in lots of different markets or companies. Theoretically, diversification allows for a net investment growth because even if one fund does poorly, the market will still yield a net increase in funds.

However, our investment committee takes a less diversified approach and searches for concentrated investment opportunities.

“If you look over the last thirty years, we’ve been one of the highest performing endowments anywhere in the country,” Korver said. “But the downside to this concentrated approach, is that there are some years, when we’re the lowest performing endowment of all big endowments, like last year for example. That’s actually just an implication of our strategy.”

How do ethics affect our investing?

Grinnell’s emphasis on ethical governance in mission and in culture carries over even into the ways Grinnell spends its money. Many investors are starting to adopt Ethical Social Governance (ESG) practices by not investing in fossil fuels, guns and other ethically questionable commodities.

Every year for six years, student groups have organized over the years to request the Board only engage in ethical investment by not investing in coal and similarly destructive commodities. Often, after sufficient research, these groups discover that Grinnell is already engaged in ESG practices.

In other cases, the Board is sympathetic to these grievances and takes the time to look into the viability of divestment; however, it is not always possible for Grinnell to reject these ethically questionable investments because it would too severely affect the gains of the endowment and the college’s financial solvency.

Does the college invest in fossil fuels?

Some student groups have made requests for the Investment Committee to implement a formal policy against investing in these resources, but the committee has yet to adopt this practice officially.

“Right now, we don’t have any restrictions in terms of investing in fossil fuels or different commodity markets,” Wilson said. “Not to put words in the investment committee’s mouth, but they didn’t think it was in the long-term best interest of the college for various reasons to restrict ourselves to managers who would not invest in fossil fuels.”

Korver also addressed the value of the college’s engagement in ESG practices. Essentially, Grinnell has, for the most part, managed to avoid unethical investing because the most worthwhile investments are also ethical ones.

“Our first job is to make sure we have the resources for financial aid and excellent programs. That’s our number one job,” Korver said. “Fortunately, we haven’t run into a lot of conflicts. … Part of it is that the ESG point of view is just a better way to build businesses. If managers have that kind of orientation where they’re concerned about the environment, they’re concerned about their employees, they’re concerned about their communities, they’re going to be more successful financially.”

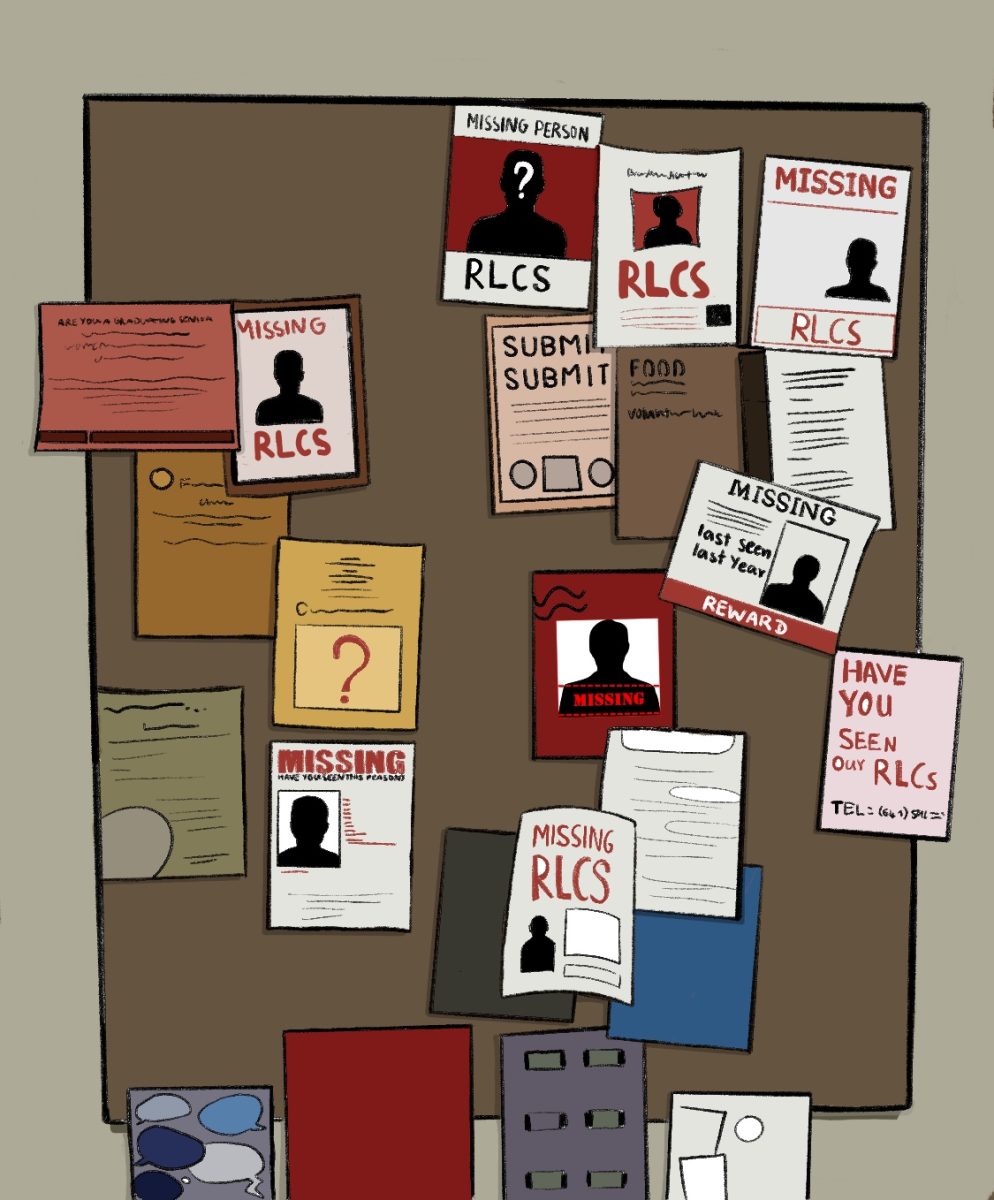

Why haven’t we been able to hire a psychiatrist?

Ethics also play a role in the college’s spending. In particular, students have raised issues about the college’s spending money on investments like the golf course adjacent to campus when Grinnell still lacks sufficient mental health providers and disability services.

According to Walker, however, guiding principles that determine how the college spends money on faculty and staff compensation, among other things, limit the college from using resources in certain ways.

“The college has a very strong commitment to fair compensation—both within and across the institution … because we want to be able to attract and retain individuals who help us deliver our mission,” Walker said.

This dedication to fair and equal pay prohibits the college from recruiting mental health care professionals by offering significantly more money than peer institutions would offer. The college cannot work against the glaring drought of mental health care professionals in rural Iowa by compensating far beyond the range of current salaries and benefits for other employees working in Student Health and Counseling Services (SHACS).

“There is also a very seriously held concern for internal equity,” Walker said. “When you cut across positions, we want to make sure that people who are holding positions of similar scope and responsibility are also rewarded with compensation that is of a similar caliber. To bring in one person at an exceptionally high compensation flies in the face of both [equity with peer institutions and internal equity].”

Because the college will not resort to, more or less, financial bribery to bring in a psychiatrist and other necessary mental health professionals, it must look to other options that can give students the help they need while still maintaining the values-based pay equity system.

“I cannot speak strongly enough about the amount of time, energy and financial resources that the college is investing in trying to build a stronger program,” Walker said. “There was one prescriber in a six-county area in Iowa. It’s very difficult when you have those kinds of shortages. … We’re on the cusp of making some very exciting changes happen in collaboration with University of Iowa and also looking at doing some things that other institutions have adopted with regard to remote access: e-counseling, that kind of thing. While we all prefer to have a person here, face to face with you, that may not be what we’re able to do. Instead of no services, we’re looking at alternative delivery of those services. I think that we’re poised to do a really fine job of that. The operating budget dedicates a lot of money towards that.”

What other funds are there besides the operating budget?

Additionally, it is very important to understand that the college’s monies are split up into many different funds and budgets, each with their own specific uses. Resources for mental health care professional’s salaries and benefits comes from the operating budget. Money invested into the purchase of the Grinnell Golf Country Club came from the strategic reserve fund—a reserve fund established in 2011 to help position our institution to take advantage of significant opportunities that come our way, according to Walker. Kington directly oversees this fund and every expenditure out of the fund must be proposed to him and receive his approval as a strategic priority. All expenditures are crafted as a one-year project or a three-year startup and after that period of time any of the related expenses are then included in the operating budget. According to Walker, use of the strategic reserve has no bearing on how we set our tuition or any other such expenses included in the operating budget spending, such as SHACS staff compensation and benefits.

As 58 acres of land directly adjacent to our campus, and facilities already used by our golf team, the golf course “was a once in a lifetime opportunity,” Walker said. “And it allows us to directly control what happens just outside our campus. Above and beyond that, it was also an opportunity, which is a strategic priority, to enhance our town-gown relationship.”

Why have we maintained need-blind aid?

Another ethical question that has been relevant to college finances in recent years is the decision on whether to remain need-blind. Ultimately, the Board of Trustees voted yes at their meeting last year, in October of 2015, but they plan to re-visit the question again in 2018. According to Walker, who worked previously at Macalester, which decided to switch to need-aware, it’s a very uprooting process that affects all areas of the operating budget and nearly every staff department, and so all of those departments and every committee in the board was involved in the conversation.

“It’s a very disruptive thing. There’s great promise about what things you think you learn and what you know in advance,” Walker said. “When we looked at, over the last three years, all the different facets of what would change … we discovered … that being need-blind is part and parcel at the core of what Grinnell is because it speaks directly to our commitment to making college financially accessible to any qualified student. When it all distilled down to that element, we were left no choice but to continue to be need-blind. … It was a very comprehensive consideration.”

The Board of Trustees was the body to ultimately make the decision. According to Jacobson, the Board wants to re-visit the decision again in three years in order to make sure we are on the revenue and expense trajectories on which we expect to be.

President Raynard Kington was unavailable for an interview.