Karol Sadkowski

sadkowsk@grinnell.edu

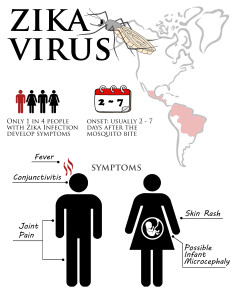

A recent outbreak of the Zika virus throughout Central and South America has caused international panic, particularly in Brazil. Zika, predominantly carried by mosquitos, has been identified as a particular threat to pregnant women for its theorized relation to microcephaly, a condition marked by abnormally small heads and incomplete brain development.

Despite extensive media coverage of Zika after the World Health Organization declared it to be a global public health emergency, many still question how the disease will affect different regions.

“I don’t think we know the extent of this pandemic,” said Professor Monty Roper, Anthropology. “How serious is this for developing countries? Does this compare to malaria, in terms of the damage that it’s going to have? Is this like the AIDS crisis? Is this river blindness? It’s an additional danger for countries that already have fragile economic systems and healthcare systems.”

Zika-carrying mosquitos prosper best in urban slums, principally in favelas in Brazil on the edges of cities, where still pools of water abound. Many people living in favelas tend to have little to no healthcare opportunities.

“There are about 1,000 favelas in [Rio de Janeiro] alone, most of them off the economic grid where rudimentary public health measures are just not available,” said Professor David Campbell, Biology.

The concern is less for communities of wealthier individuals who, according to Roper, “can afford to stay inside.”

International observers also hold a stake in the Zika outbreak, as the possibility of the virus’ spread beyond Latin America worries countries like the United States.

“Theoretically, if somebody was infected in tropical zones and flew up here in the summer, it could technically be spread from person to person,” Campbell said.

Richard Bright, Director of Off-Campus Study, said that students considering studying abroad in affected countries should review updates from official sources like the U.S. State Department and the Center for Disease Control.

“Our approach in the off-campus study office is to help students … to take responsibility for self-informing and for taking precautions against contracting particular illnesses,” Bright said.

Currently the U.S State Department has not issued any travel warnings against affected Latin American countries. Bright added that the Off-Campus Study office will not make its own judgment calls on public health issues.

“When you think about the fact that you’ve got 200-some-odd students studying in maybe 35 or more countries, that’s something you do take seriously,” he said. “Part of taking it seriously is my knowing that I’m not the authority. We defer to people who are.”

As long as official sources do not issue warnings, Bright said that students planning semesters in affected countries should be aware of the risks involved and make their own informed decisions.

“Whatever is being said about Zika … students and families ultimately need to decide for themselves whether any risks that may be associated with Zika for them are risks they wish to run,” he said.

Bright also added that students who have already committed to countries affected by the virus may switch programs to avoid encountering Zika or any other public health concern.

Still, given the unknowns about the virus, some think the international hysteria surrounding the Zika virus could be greater than the on-the-ground reality.

Leading experts say that while the Zika outbreak is dangerous, efforts should be focused on disease prevention more broadly than on specific outbreaks.

In an article published by The Guardian on Feb. 17, Leslie Lobel, an Israeli physician who helped work on developing and Ebola vaccination, stated that the hysteria surrounding Zika may be counterproductive.

“There’s a lot that might be done that is not being done in a corrective way to control all disease, not just Zika,” he said. “This is just the tip of the iceberg. There are going to be a lot more.”