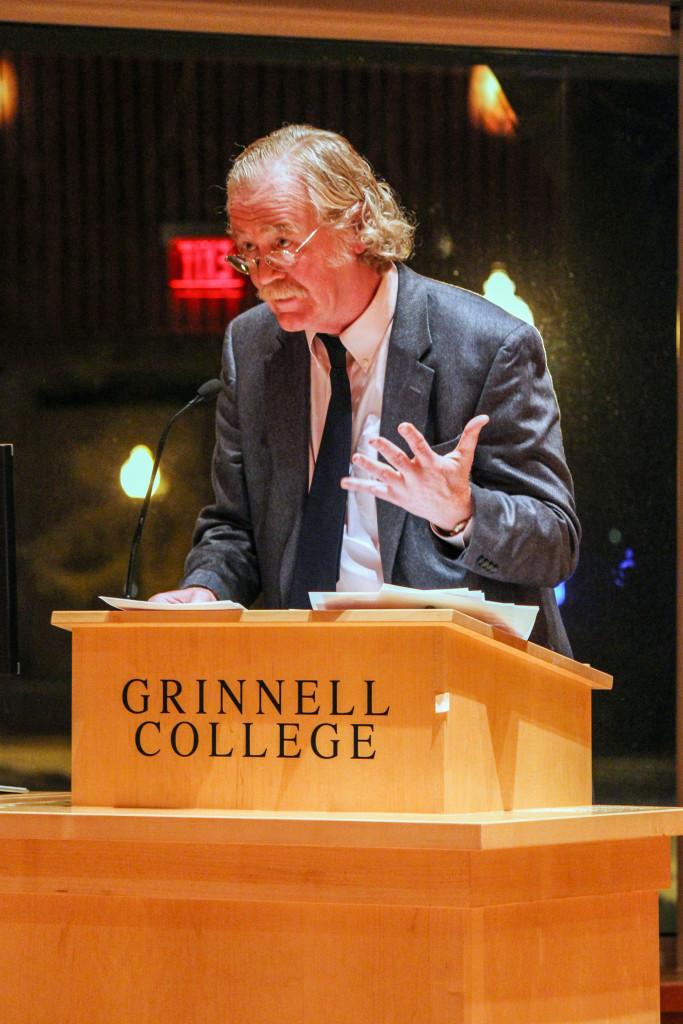

Looking at 19th and 20th century literature, the cultural idea of sacrifice that went into World War I came out a changed, isolated figure. On Thursday, March 5, Vincent Sherry, Howard Nemerov Professor in the English department at Washington University in St. Louis, spoke in JRC 101 about sacrifice as a shifting cultural idea in Europe throughout the First World War. His talk was titled “Bare Death: The Failing Sacrifice of the Great War” and was sponsored by the Center for the Humanities.

As Sherry explained, before the First World War the cultural idea of sacrifice was that of an individual making small concessions rationalized on the grounds of improvement.

“Sacrifice was understood as a rational practice … The word was all over the place … You sacrificed some aspects of yourself for the betterment of yourself and the betterment of society,” Sherry said.

Photo by Misha Gelnarova.

However, he noted that this concept was complicated by the loss of so many lives in the war.

“The individual was the measure of useful sacrifice. What happens to that when you get people dying by the millions?” Sherry questioned. “That idea of the individual sacrifice … is just blown apart. You have to use that idea to justify millions of deaths, and it just breaks down.”

Sherry added that the breakdown of the old concept of sacrifice was further expanded by what he labels as the lack of true cause or need to have begun the war.

“This war was for almost everyone involved a mistake, in that there was no confirmed rationale for [anyone] … You could invent them and hype them … but the fact is that the war happened kind of inadvertently,” Sherry said.

As he explained to The S&B, a multitude of scholars have written on the history and literature of World War I. In Sherry’s talk, he outlined his ideas in dialogue with many of them, including Giorgio Agamben, Paul Fussell, Ford Madox Ford, Malcolm Bradbury and Richard Aldington. According to Sherry, what makes his approach fresh is that he works to put WWI texts from all involved Europe nations in dialogue all together, as they were at that time in history.

“It’s always written … from the individual national protagonist. I’m trying to put the literatures of Europe in conversation with each other. Because [soldiers and citizens and authors] were reading each other,” he said.

During his talk, Sherry pointed to an image of a WWI soldier on the cover of “The Great War and Modern Memory” by Paul Fussell as the resulting image of sacrifice from the war—a solitary individual and thereby the understanding of sacrifice that continues to today.

“An individual out there alone suffering the desolation of his abandonment. … That is an understanding that cycles through the literature of the war. … It is not the image of sacrifice that went to war,” Sherry said in the talk.

The interdisciplinary, internationally comparative research Sherry has been doing with the shifting image of sacrifice will be included in “A Literary History of the European War of 1914-1918,” a book he is working on for the Princeton Press.

While Sherry was on campus, he also had lunch with students and visited a class to discuss James Joyce’s “Ulysses”—another large topic in his career of research and literary history work.