Over the course of the last week, unidentified people have removed or vandalized two separate art pieces that represented protest and resistance to the new presidential administration.

Clio Sawyer*, a student at Grinnell, created and hung posters across campus that read “No Safe Spaces for Fascist Scum” with an image of a boot stomping and destroying a swastika.

The day after Sawyer put them up, another student hung a poster in response that reads “In Staub Mit Allen Feinden Gross-Deutschlands” which translates from German to “Into Dust with all the Enemies of Great Germany” accompanied by an image of a fist crushing three enemies and a caption reading “Taken in Summer 1940, Germany” with a quote from a Belgian communist leader, Georgi Dimitrov. The student also photocopied the original poster and next to it wrote, “January 24, 2017 at Loose Hall Entrance,” to compare the original poster with the sign from Nazi Germany.

According to Professor Dan Reynolds, German, the enemies depicted represent the U.K., France and “International Jewry”.

“World War II had broken out, and France and the U.K. were at war with Germany,” Reynolds wrote in an email to The S&B. “Germany by this time had occupied or annexed half of Poland, all of Austria and the Czech half of Czechoslovakia in the east, Belgium, the Netherlands, and part of France in the west.”

According to Reynolds, the juxtaposition between the three posters provides commentary on nationalism in America.

“[American nationalism today] seems less concerned about communism in the post-Cold War era and more obsessed with migration, race and Islam,” Reynolds wrote. “What I find ironic is that the image of a boot crushing a swastika is also familiar within communist iconography, such as the Treptow Memorial in Berlin, where a Red Army soldier stands on a crushed swastika.”

Sawyer’s poster concerns how anti-fascism opposition rhetoric impacts communities.

“When fascists feel emboldened, they tend to do a lot of really awful shit, and in general, fascism accumulates power by testing people,” Sawyer said. “So the more you show them you’ll tolerate it, they’re seeing that you’re not going to fight back and they’re just going to push the envelope further and further.”

Sawyer had been using this poster and other art pieces to protest against and to resist fascism, which they associate with the new Trump administration.

“We’re living under the beginnings of a fascist regime. Any kind of visceral response to that should be justified,” Sawyer said. “For me personally in that moment it was this means of dealing with my feelings of powerlessness. … If people were feeling anger towards this and had a lot of thoughts of aggression towards this new regime and the rise of white nationalism in the U.S. and people were like, ‘you can’t feel that,’ I think art is a really important way to communicate that you’re experiencing things too.”

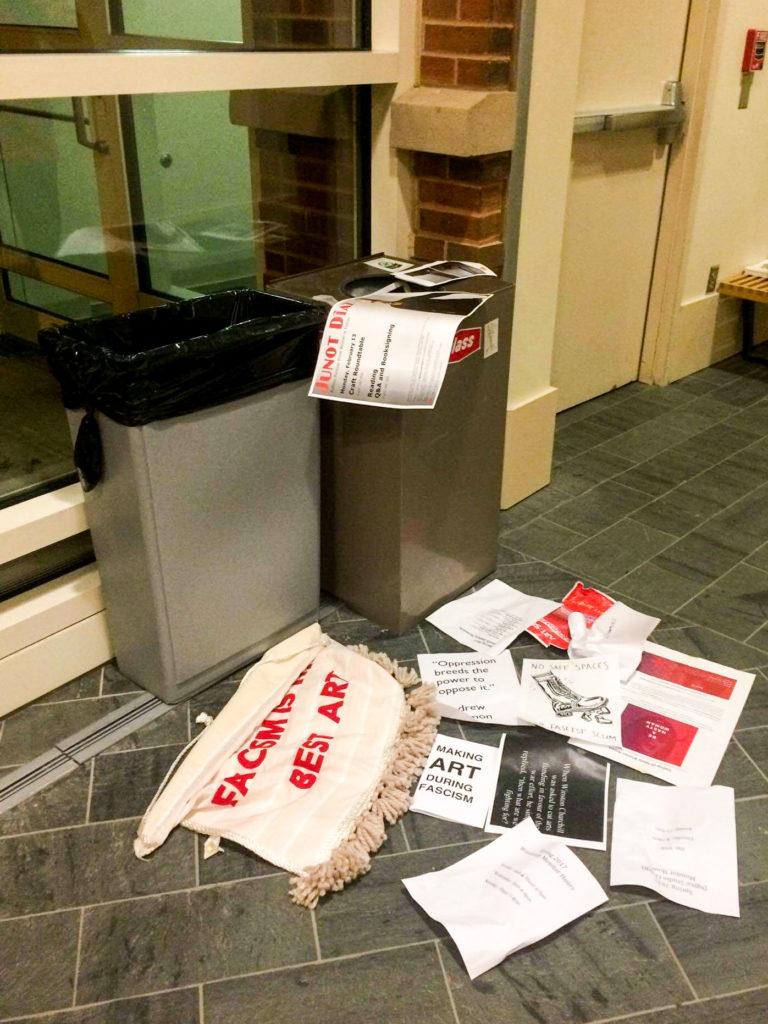

In a separate incident, the Art SEPC bulletin board was torn down, including a sign that read “ART RESISTING FASCISM IS THE BEST ART,” last Wednesday.

According to Professor Lee Running, art and art history, visual art has historically been used as a form of protest and resistance against things that people think are wrong. She says that art is “an activity that notices things,” and she teachers her students to observe carefully to understand and make sense of the world around them.

“We spend an incredible amount of time looking and analyzing with our eyes what we actually see,” Running said. “I think art is an incredible tool for being able to look at something – whether that be an object or a political situation or a social situation and be able to extricate information from that act of physically looking at something.”

Last semester, Running and two groups of students sewed two banners: one in support of protesters at Standing Rock, which pictured two heads of buffalo with the words “We Stand,” and one in support of those protesting the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) which pictured an anatomical heart with images of waterways in the shape of Iowa moving through it.

Art can also be used as a soothing method in hard times. While these two uses of art, resisting and healing, can go together, they are not inherently the same.

“I think they’re two different things. If you’re asking for art as a tool of soothing, I think that’s a totally different thing than art as a tool for mobilizing or getting a particular message to the public,” she said.

The recent Women’s Marches across the country saw the use of art as both protest and healing. Countless women participated in the PUSSYHAT PROJECT, knitting pink hats with ears and wearing them to the marches to make a statement. Running attended the march in D.C. with a pussy hat on her head.

“When driving from Iowa to Washington D.C., at every rest stop, people knew who we were and where we were going because we had a visual signifier on our heads. … We were hugged and talked to and the rest stops were full of women all the way across the country,” Running said. “People talked about this being a cathartic act to knit these. I talked to many women who were knitting them in mass … putting our hands to work in a time that seems like there is so much that is so wrong.”

Running was also inspired by the art at the Women’s Marches because protest signs did not have one slogan and was instead made up of the collective thoughts and actions of the millions of people who attended.

“I was moved at how many signs were made out of cardboard and Amazon boxes and tampon boxes specifically,” Running said. “To have a march in which the signs are made out of corporate rubbish has its own meaning.”

As cathartic and inspiring as art can be, however, Sawyer cautioned against using it as the only form of resistance, particularly against fascism and the current administration.

“I don’t think art is insignificant, but I don’t think it’s the biggest part of resistance. I think the biggest part is to have a sustained, cohesive mobilization from leftist organizations, because fascism doesn’t start and end in America with Donald Trump,” they said.

Running also outlined some concrete actions which can act together with making art.

“I encourage my students to use visual as one way in tandem with essay writing and letter writing and I think there are lots of ways to resist. The visual, and physical, is definitely a method with a long, long history, fraught with controversy, and that isn’t new,” Running said. “All forms of debate, letters to the editor, letters to politicians, are also places where people have protested over time.”

*Name changed to protect the anonymity student