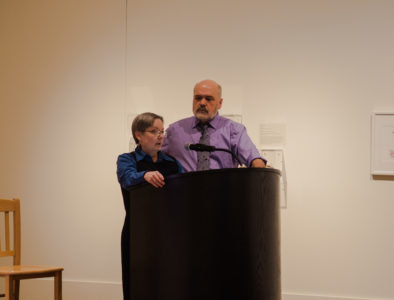

Tinker Powell and Mark Montgomery are economics professors at Grinnell College. They recently wrote a book on international adoption, called “Saving International Adoption: An Argument From Economics and Personal Experience.” The S&B’s Amanda Weber sat down with them to talk about the book.

The S&B: What made you want to write about the topic of international adoption?

Mark Montgomery: Well, we’re international adoptive parents. We have three children: we have a birth child who’s 32 now — a Grinnell grad — we have a son who’s 26, who was [adopted] in infancy from Texas — he’s African American — and then, about 18 years ago now, we adopted a boy from Sierra Leone at six and a half in West Africa. I guess the thing that got us interested in writing the book was international adoption is collapsing, and we wondered why. The other thing we wondered about was why so few African countries [are] putting kids up for adoption when they famously have an orphan crisis after AIDS. So that was sort of the motivating factor.

The S&B: How did the two of you decide to collaborate on this project, and what was it like to co-write a book?

MM: Here’s how I like to answer that question. Anything that doesn’t kill your marriage makes it stronger. We had written a novel about twenty years ago which we got published.

Tinker Powell: And our marriage survived that too, so we thought it would probably survive another.

MM: We enjoy working together to some extent.

TP: Our skill and what we like to do in research kind of mesh. I like to do the background research and he puts things down the first time and then I edit it, and we plan it together.

The S&B: You mentioned writing a novel — what was it like to transition from fiction writing to very much non-fiction writing?

MM: This is our first non-fiction collaboration. We wrote a novel years and years ago. … We’re number-crunchers, so it’s weird to be writing at all like this.

TP: So it was more of a transition from that kind of writing more than from the fictional writing we had to do.

MM: We did the fiction as just a lark, just for fun.

TP: That was very much in our spare time. Whereas this is part of our research.

The S&B: What was the process like for gathering the evidence and research utilized in the book?

TP: This is a mixture of some background research … on some aspects of adoption and international adoption and some research on history of adoption, and then we also went to countries in Africa and talked to people who were actually in government … and directors of orphanages and then birth parents of children who had been placed for adoption, and then we talked to some adoptees in the U.S. and adoptive parents of kids from Africa.

MM: So it was a lot of background reading. There was some field work, which is unusual for economists. … Our daughter lives in Africa so she helped us get meetings with some government officials in Rwanda, where she lives.

TP: It wouldn’t be called field work by social scientist standards of people who really do field work for research.

MM: But we went out and talked to people and that was something we had never really done before in our whole lives of research. Our research was getting data, putting [it] in the computer, crunching the numbers, getting the numbers out, and publishing them — that’s what we did for 20 or 30 years.

The S&B: What particular challenges did you encounter when you countered the common conceptions about international adoption?

TP: Well international adoption is collapsing. … And one reason why it’s collapsing is that there is some opposition to international adoption that is based on the idea that it’s bad for kids to be taken out of their birth culture, and so that’s one thing that we challenge in the book.

MM: We also are going against the grain in the sense that the international agreements governing adoption are very, very, very specific. That you must not ever give the birth family any compensation for this child, because that’s selling children. … Well, we’re economists, and we’re saying that’s a mistake. You’ve got to let the adoptive parents and the birth parents get together … and that may involve some passing of resources between them.

TP: And a couple of the other reasons we went to that sort of solution for the problem, which really goes against the grain is that when we interviewed birth parents in Africa … what they wanted was to have had more contact and to … be able to communicate so that they know that their child is doing okay, and to possibly, when they are adults, have the child come back and reestablish the contact at that point. It’s much easier to do that if you use a more modern American open-adoption law which involves contact before the adoption is decided on really, and before the adoption takes place.

The S&B: Was there anything about the process of writing the book that really surprised you?

MM: It was interesting that we could do this kind of writing, because we hadn’t done this kind of writing before. That we could pull this off to write a book instead of a number-crunching paper, which was only written for economists. … We worked really hard to make it interesting to a general reader — whether we succeeded remains to be seen.

TP: At least we succeeded enough to get it published.