For the past 72 years, the Robert N. Noyce `49 Science Center, used by Grinnell College students for classes, labs and research, has not always been the maze of winding halls and classrooms that it is known for, having undergone two major renovations with multiple other additions and changes to the layout.

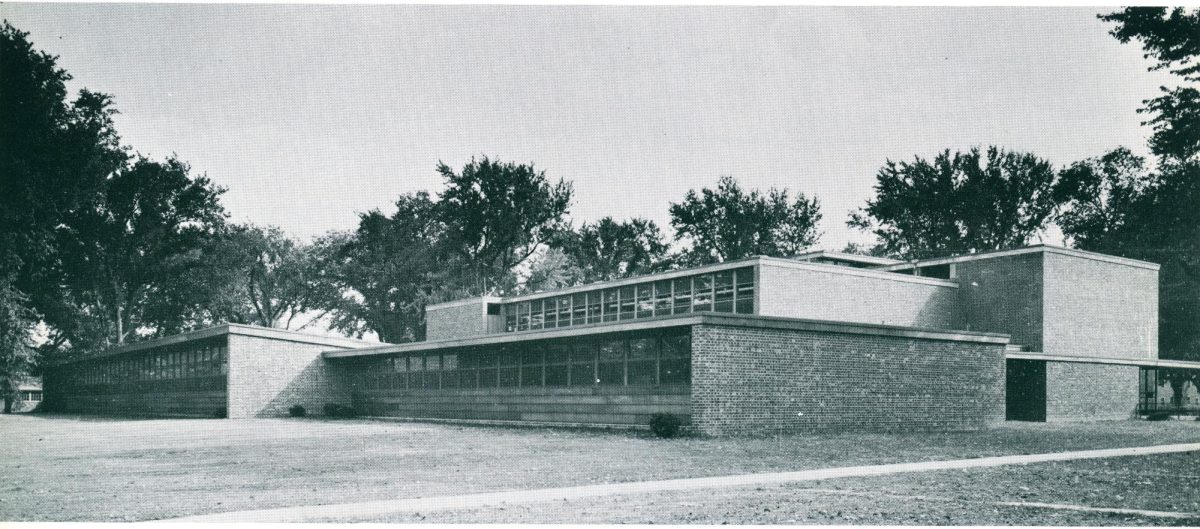

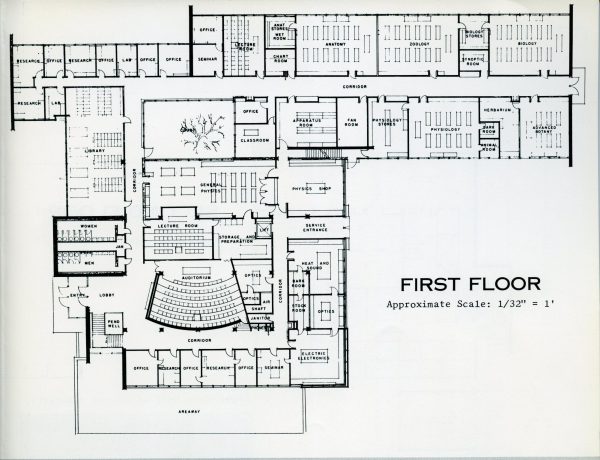

Constructed in 1951, the original building, named the Hall of Science, was a 2-story, 67,000 square foot structure that cost $1 million to construct. It originally housed the biology, chemistry and math departments, and it gave each faculty member at the College access to research laboratories for the first time, according to a progress report by then President Samuel Stevens.

Jim Swartz, chemistry professor at Grinnell, chaired the committees that led to two of the most recent construction projects, spanning from 1995-1997 and 2005-2007.

Swartz, chair of the chemistry department at the time, asked Pamala A. Ferguson, then Grinnell College president, if he could write a grant proposal to fund renovations for the chemistry labs. The science building planning committee was then convened, run by faculty as opposed to administration.

The first phase started construction in 1995 and cost $18 million. This construction was renamed the Robert N. Noyce `49 Science Center that same year, adding the elbows, a south side strip, light monitors and new classroom pods into the existing Noyce buildings.

The initial renovation plan sought to add another wing onto the southwest corner in place of the original elbows. However, the committee’s concern was that there would be limited natural light if another building was erected separately. Instead of creating a new wing, the architects proposed to design a structure that would let in natural light by creating an opening in the building layout, unifying the conflicting renovations.

“I remember one of the architects saying that bakers solved that problem a long time ago — it’s called a donut,” Swartz said.

Alongside the renovations, the College also wanted to implement new approaches to teaching. Charlie Duke, professor emeritus of physics, was dean of the College at the time, and he said the College implemented Project Kaleidoscope, changing the way Grinnell science faculty created curriculums and taught first-year courses.

While deliberating design plans for new chemistry classrooms, Swartz said the faculty had an idea of what they wanted, and one of the architects came up with the plan of using tiered classrooms that provided two tables per tier — sitting in loose chairs, the students could turn around and converse with one another in groups.

“It’s a good example of why diverse groups of people come up with better solutions,” Swartz said. “It also illustrates that we wanted to use much more engaged, pedagogical approaches rather than students being passive receivers of information.”

The second phase of renovations started in 2005 and cost $40 million. This time, plans involved the construction of a 3-story, 108,000 square foot addition that housed the Kistle Science Library, biology, computer science and part of the math and psychology departments.

“We actually hadn’t intended for this to be three floors, but there wasn’t any space if we didn’t go up,” Swartz said, explaining why the third floor of Noyce is only accessible through the north staircases.

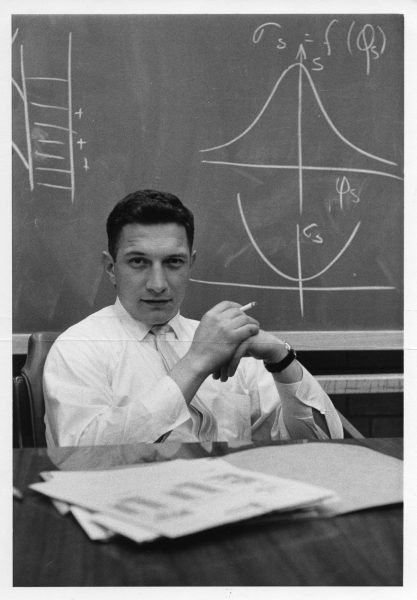

The center’s namesake and notable Grinnell alumni, Robert Noyce, grew up in the town of Grinnell, attending and graduating from the College in 1949. At Grinnell, he competed on the men’s swim and dive team, and he was inducted into the Grinnell College Athletics Hall of Fame in 2002. As a math and physics major with a doctorate in electrical engineering at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, he also co-invented Fairchild Semiconductor, an international semiconductor company, and was the co-founder of Intel.

When Swartz started working for Grinnell in 1980, Noyce was on the board of trustees. The two of them argued about a few things, and according to Swartz, he was “too young to be revered” by Noyce.

After Noyce’s death in 1990, Swartz started to learn more about him. “He was a really amazingly effective person. One of the things that he really did that he is underappreciated for is [creating] the atmosphere for a boom to the technology industry.”

“As Bob said, one of his mistakes is that somebody at one point pitched the idea of a personal computer, and he couldn’t understand why anyone would want a computer of their own,” Swartz said. “That was a multibillion dollar mistake. That Intel could have done that, but they didn’t.”

Reflecting on Noyce’s legacy and the years of renovations the science center went through to become what it is today, Swartz said he was thinking about how the Noyce Science Center creates a learning environment to support his students.

“Not everybody is Noyce,” he said, “but that’s the kind of education platform we want to provide to help support students to be able to do the kinds of things that he did, whether that’s in social justice or whatever.”