Michael Williams kept in touch.

In 1996, the then-20-year-old moved from Syracuse, N.Y. to Kearney, Neb. Seven years later, he moved to Grinnell, Iowa. Finances made visiting his daughters in Nebraska difficult and in the 24 years since he left, Williams returned to Syracuse only three times, most recently in 2012.

Still, Williams was in constant contact with his family.

His daughter Malika Williams, 21, of Kearney, said that her father would call her and her sisters as often as possible. They would talk about everything and anything they could. Rochelle Pagan, one of Williams’ first cousins who still lives in Syracuse, spoke similarly.

“He never stopped that. He contacted every one of us, frequently,” said Pagan. “It was like he was still here, but he was [out] there.” Williams would call or text Pagan and other family in Syracuse nearly every day.

“He was always calling, checking in on us,” she said. “Even though we were more worried about him [out] there.”

The cousins would reminisce about growing up together. Williams would update his family on his health and how he was trying to stay on top of his diabetes. They would send photos back and forth of their kids and grandchildren.

He was always calling, checking in on us. Even though we were more worried about him [out] there. – Rochelle Pagan

So, it was not unusual when Williams called his cousin on the afternoon of Sept. 12. Pagan was at work, so she did not answer the call. Instead, she texted Williams: “Hey cuz, I’m at work. You good?” He replied that he was dealing with some pain but told his cousin not to worry. He said he would call back when she got off work.

Pagan was the last of Williams’ family in Syracuse to hear from him.

Later that evening, on or around the 12th of September, 44-year Michael Williams was killed.

For four days Williams’ whereabouts were unknown, until the afternoon of Sept. 16 when police identified a body burning in a ditch in rural Jasper County, near Kellogg, Iowa. As of Sept. 22, four suspects are accused in the alleged murder of Williams.

“I know I couldn’t have helped him at that moment,” said Pagan. Still, she cannot help but wonder what he was feeling when he texted that last time. “But I know he’s okay now, and he was just trying to tell me he loved me.”

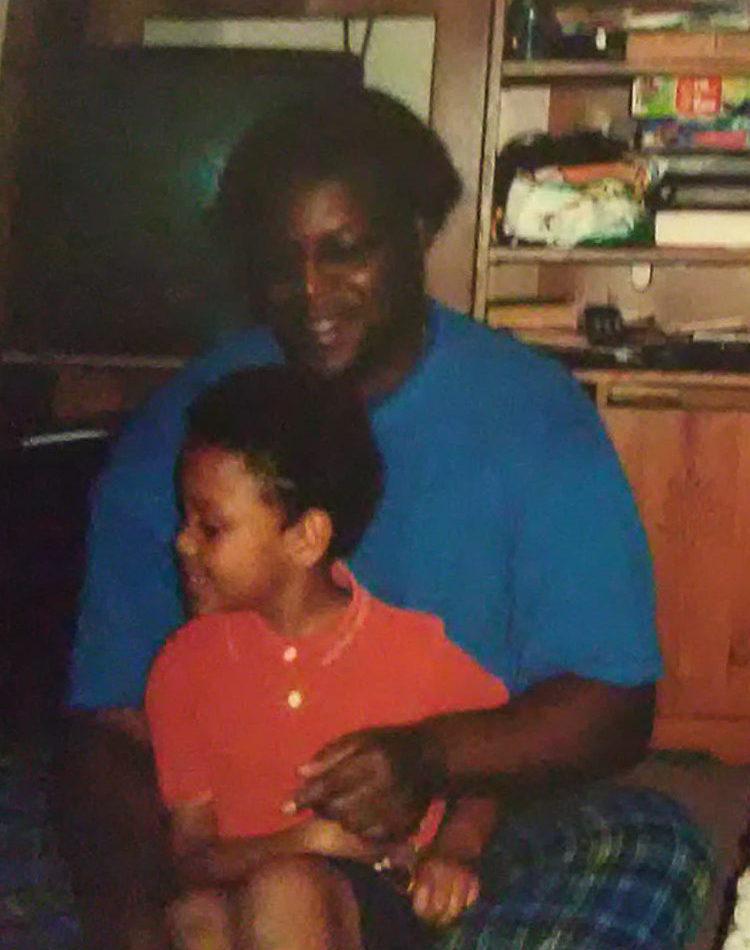

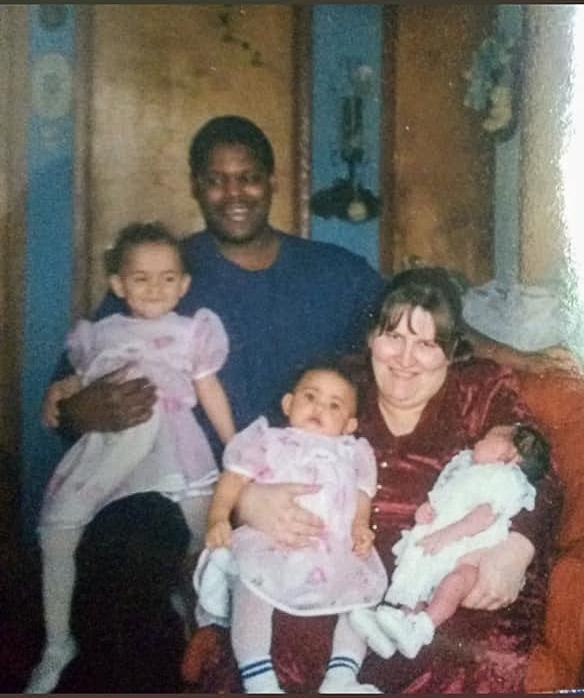

A Proud Father

Williams’ life was defined by who he was to his family. In Grinnell and Kearney, he was a father.

Williams is survived by six children and one granddaughter: Dorriya, 22, and Malika, 21, and Malika’s daughter Dawnella Williams, six months, of Kearney, Neb., and Danté, 17, Michael Jr., 13, and Jameka, 12, of Grinnell, IA, and Allishia Swearingen. Williams never met Swearingen due to his estrangement from Swearingen’s mother, and her age and location are unknown. Williams’ oldest daughter, Shartraya Williams, died on Dec. 8, 2018.

Williams also leaves behind two ex-wives, Sharta Williams of Kearney, Neb., and Janalee Boldt, of Grinnell, Iowa. As they grieve the loss of their children’s father, both recall memories from early in their relationships with Michael, memories which capture the care with which he fathered.

Sharta Williams recalled coming home to find Michael scrubbing the walls, ceilings and floors of their apartment. All the furniture was pushed to the center of the room. Michael, fixed on preparing the house for the couple’s first daughter, would deep-clean weekly. While Sharta convinced Michael he only needed to clean like that every few months, in his actions was an apparent desire to create a safe environment for his family.

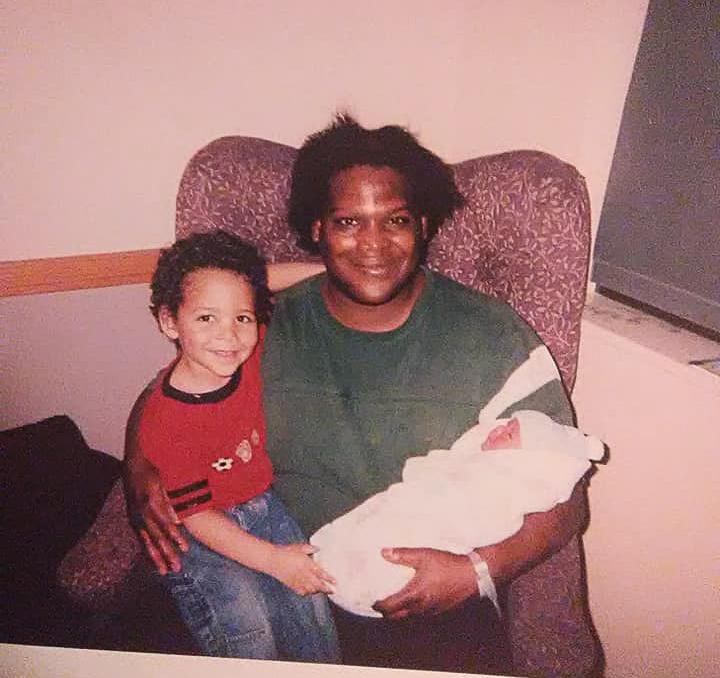

Boldt remembers that in the middle of the night, Williams would jump up at the sound of one of their children’s unrest. He would rock and sing to the children. He was the first person to hold each of his three children with Boldt.

“That’s what he wanted,” said Boldt. “Just to hold his babies.”

In a series of Facebook messages with The S&B, Williams’ friend Angel Carman remembered how Williams would talk about his family, especially his mother, whom he planned to visit soon. He would talk about his kids and how he hoped they were respectful to each other, their peers and their mother. He was excited to be a grandfather.

“When he got to see his granddaughter on video call for the first time the joy in his face was unbelievably adorable,” wrote Michael’s daughter Malika Williams over Facebook Messenger.

Williams’ never met his granddaughter Dawnella, but Malika says that when she’s older she will tell Dawnella that Williams could not have been prouder to be a grandfather, a father and a friend.

“Her grandpa loved his family very much and did everything for his family. … If he was here today, he would be the same goofy person that made this family smile in hard times like this when a smile was needed the most,” wrote Malika.

Of course, Williams’ role as a father took him far from his family in Syracuse. His move to the Midwest was difficult for his East Coast relatives, especially as they worried about their son living in unfamiliar rural communities.

But ultimately, as Pagan describes it, “he wanted to be his own person. And that’s why he moved, to go be with his children.”

A Caretaker

Williams’ tendency towards conscientious caretaking extended beyond the memories Boldt and Sharta Williams shared from their children’s infancy. Caretaking was constant for Williams, who employed humor to remind those around him of his continued support.

When they first met about seven years ago, Williams’ friend Angel Carman says she looked into his eyes and could tell he had a huge heart. She describes Williams as a brother to her, as well as one-time roommates. Whenever Williams and Carman had a disagreement, they would talk it out.

“What is being said about him being a gentle giant is true,” wrote Carman over Facebook Messenger.

“When you’re about ready to cry, or if you’re mad at something, you are going to forget about crying or being angry at whatever, he’s going to make you start laughing,” said Boldt. “And that’s what I’m going to miss, because this last week, I’m saying, ‘I need you here because I keep crying and I’m so angry at what happened, and I need justice done. Where are you? I need to smile right now.’”

Since Williams’s death, Boldt has been dancing and singing for her kids. She says she feels sorry for the silly scene she puts on, but she wants her two youngest children to remember the joy and entertainment their father brought during trying times. Sometimes, if the kids were upset and humor was not the immediate remedy, Williams would take them on walks around Arbor Lake or in town.

For varying reasons, both Boldt and Sharta Williams divorced Williams. In their memories of him, though, neither woman seem to harbor resentment towards their ex-husband. Both described how Williams talked about improving himself for the benefit of his children. Sharta Williams said that, like many, he struggled with drinking. He was trying to be better about his health. He wanted to get his G.E.D., despite managing a learning disability.

Williams dreamt of becoming a nurse. He was constantly trying to find ways to help others. At the same time though, to Boldt, it “seemed like he was always putting himself last,” in order to make sure everyone around him had a smile on their face.

If he was here today, he would be the same goofy person that made this family smile in hard times like this when a smile was needed the most. – Malika Williams

The Facebook group JusticeforMike was started by Boldt’s friend Missy Watkins as a forum for those who knew Williams to share their memories and post updates concerning the case. In one post, Boldt shared how Williams had cared for her after a surgery. The daughter of one of Williams’ friends commented and expressed gratitude for the aide he often offered her mother by carrying her groceries and walking her home.

Similarly, Sharta Williams remembered that once, early in their marriage when Williams was working in an assisted living facility, she visited him at work and the patients told her of his care: he never rushed them and he was always eager to share stories.

This dedication to others has long been ingrained in his personality.

As children, Williams and his four siblings, one of whom died when Williams was young, lived in the same house as their five cousins, including Rochelle Pagan. Pagan remembers that growing up, Williams would always look out for his cousins. “[He] just wanted to protect us, make sure we were staying on our game like he was.”

As with his children in adulthood, Williams in his adolescence enjoyed his family and being around them. At gatherings, he would bring the fun. He would dance. His laugh was infectious. “He had this crazy old laugh,” said Pagan. “He used to laugh like Scooby-Doo.”

He Could Talk to Anyone

Williams’ Scooby-Doo laugh could be heard all around Grinnell. He took frequent walks, stopping at Arbor Lake, sitting in Central Park or swinging by Casey’s General Store. Anywhere he went, Williams stopped to chat, and by the end of the conversation, he likely had the other person laughing.

When he worked at McDonald’s, his laugh was heard there, too. Cherie Reader, one of Williams’ former McDonald’s co-workers, wrote over Facebook Messenger, “We [would] sing at work, we [would] dance at work, just out right had fun at work.”

Williams once stopped Scott Breckenridge on the street after seeing that Breckenridge’s girlfriend’s son was wearing a Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles t-shirt. The two men discovered their shared love of the series and became fast friends, frequently barbequing and playing Dungeons and Dragons or rummy. This was about ten years ago, and the two were friends ever since.

Williams and Eric Wadhams met at a gathering hosted by Breckenridge. Over Messenger, Wadhams wrote that while he does not keep many close friendships, he considered Williams a kindred soul. “Anytime we would see each other we would stand around and talk about life and get caught up no matter where we were,” wrote Wadhams.

“He could just be invited to a place, and then everyone would gravitate towards him and start talking to him and want to be his friend,” explained Williams’ daughter Dorriya. “And I would say, ‘How did you do that? Show me the magic ways!’”

Last September, late in the evening on Friday the 13th, Henry Brannan ’21 was biking south down East St. when he encountered Williams. Under a streetlight, the two struck up a conversation. It must have been around midnight, but they talked for over three hours, eventually beginning to walk through town.

He had this crazy old laugh. He used to laugh like Scooby-Doo. – Rochelle Pagan

The two kept in touch — mostly via Facebook — and, months after their initial meeting, Williams asked how Brannan’s grandmother was over Messenger. The message struck Brannan as exceptional: not only had Williams kept up communication after a chance meeting, but he had remembered without provocation a fleeting comment Brannan had made about his concern for his aging grandmother. Brannan does not claim to know Williams very well, but the nature of their friendship spoke to Williams’ warm personality.

“The way he approached other people, I think that’s really what’s amazing about how he lived his life,” said Brannan.

Today, the streets and parks of Grinnell no longer ring with the sound of Michael Williams’ laughter. His easy, eager conversation is missing from chance interactions and long-held friendships.

For Pagan, the pain of losing her cousin is overwhelming. Seeing the support of the community in Grinnell, though, is helping the family process their loss.

“We know him. So, we said this makes sense, that he was loved down there. Because of his personality and how he can just make somebody smile at any given moment. And when Michael comes around, it’s automatic.”

A life mourned

With sadness and sympathy, and in reaction to the horror and cruelty of Williams’ death, just over 75,000 dollars have been raised via two separate GoFundMe campaigns organized by Williams’ family. These funds will be used to bring his body back to Syracuse and to cover the cost of transportation for his family to attend the funeral service. Additional funds will be used towards legal fees and other costs associated with his family attending the trial. Adamant is the community that demands #JusticeforMike.

The funeral rites for Michael Williams are scheduled for Oct. 8, at the Well of Hope Church in Syracuse.

Sharta Williams, Boldt and Pagan all said that they’re sure Williams is in heaven. Reassured by memories of the man they lost, his family knows that Michael Williams’ is looking down upon them, playing spades and laughing hard.

Chloe Wray is a freelance writer for The S&B. She is a fourth-year Anthropology major with a concentration in American Studies from Ithaca, N.Y.

M. Taylor • Oct 10, 2020 at 1:14 pm

Thank you, Chloe.

Michael’s family, and the Grinnell community, needed to read your article.

Thank you for capturing his character and spirit with such sensitivity.