Apologizing for the interruption, an employee of Saints Rest Coffee House tells Betty Moffett that someone is on the phone. They’re asking where they can purchase a copy of Moffett’s new book. Moffett asks the employee to tell them it’s available at the Pioneer Bookstore.

Moffet took this brief interaction in stride. The use of Saints Rest as a directory for community information, an interest shared by many Grinnellians in supporting the work of fellow community members and the fact that Moffett just happened to be in the cafe all stood out as a nod to the interconnectedness and coincidence which defines small-town living.

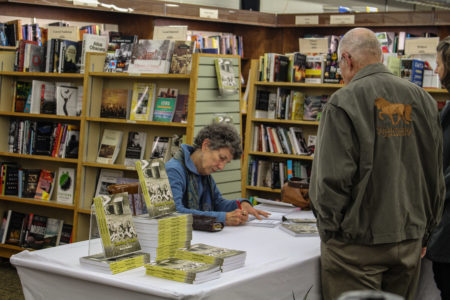

Released on Oct. 5 by Ice Cube Press of North Liberty, Iowa, “Coming Clean,” is a collection of 19 short stories authored by Moffett. Based on Moffett’s memories of North Carolina and Grinnell, Moffett introduces readers to the characters who have dotted the communities she has called home.

For Moffett, small exchanges have made small town living in the South and the Midwest alike. “There are funny little relationships that you have in a town this size, and you can’t push those boundaries, you can’t overstep,” said Moffett. This advice is echoed in her story “Mirror, Mirror.” A reflection on the relationship between hairdresser and customer, Moffett explores an imagined friendship between the two. Moffett claims that the small-town boundary provides comfort, establishing a standard for the relationship that must grow patiently with time. Moffett came to Grinnell with her husband, Professor Emeritus Sandy Moffett, theatre and dance, about thirty years ago. As a member of Too Many Strings Band and a former director of the Grinnell College Writing Lab, Moffett’s interests intersect with different art forms — writing, theatre and music — all platforms that can transport someone into the experience of another.

The stories are set in the communities Moffett has called home, and the characters in her books are people who the reader may imagine nodding to on the street. The book grants readers knowledge of the characters’ shortcomings and a fondness for the peculiarities Moffett poses as strengths.

Communicated through dialogue, the development of characters is given priority: lines of description detailing the setting are forfeited in favor of creating three-dimensional characters. It is through these characters that the reader gets a sense of the book’s setting. Once the reader knows the subject of the story they are equipped with a notion of how such a person might surround themselves, what setting would best suit them.

“I’ve never been particularly interested in when or where,” Moffett said, explaining her focus on dialogue and the piecemeal nature of the stories’ chronology. It is here that Moffett’s stories become recognizable not as memoir but as fiction.

There are some things Moffett does not remember and some things she is not going to tell. Some things she will lie about. For her, the lines between memoir and fiction are permeable. She cannot make up the basis for what she writes about, but she is not opposed to changing what does not fit, what she does not like, and reworking the story in hopes of resolution.

“Somebody said once, and maybe particularly with short stories, ‘Start from the hurt.’ It doesn’t mean disaster, it doesn’t mean tornado, it doesn’t mean murder, but start from something that hurt you,” Moffett said. “And if you feel something, then it transfers from wherever feelings lie into your mind and your memory, and you remember those things.Sometimes the hurt gets resolved, sometimes you find a way around the hurt, and sometimes the hurt is not resolved.”

“Brothers” is one such story exempt from resolution. Professor Ralph Savarese, English, wrote in a statement printed on the back of the book, “By holding back, [the stories] reveal life’s mysteries all the more, and they pay homage to the laconic dignity of the people Betty Moffett writes about. The final story called ‘Brothers’ will break your heart in the best possible way.”

One of the first stories Moffett ever wrote is the collection’s opening account, “The Store.” Written about thirty years ago — around the time she moved to Grinnell — she had just begun meeting with a group whose membership oscillated between four and eight writers who shared poetry, short stories and encouragement.

“That was my daddy’s story … he never told it the same way twice. Nobody did, nobody told stories the same way — they added things, it was expected, it was entertainment,” Moffett said.

Years ago, when she first asked him to read the story, he replied that it sounded familiar, but he did not recognize any of the characters. Somewhere along the line, between his telling and her filtering it through her mind, the interpretation changed.

The stories of her childhood have undergone evolutions and revolutions, a process Moffett says steeps her stories in nostalgia. Growing up in a family of storytellers, family tales were committed to the “Ferguson Family Anthology,” a source of collective memory. Such is the nature of storytelling; such is the nature of memoir becoming fiction.

Moffett will read from her collection at the Grinnell Arts Center on Nov. 11 at 4 p.m. alongside the music of violinist Professor Tammy McGavock, economics. Her book is available at the Pioneer Bookstore.