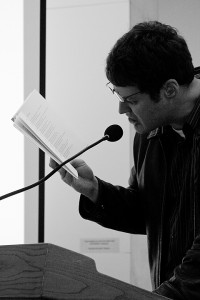

Ilya Kaminsky is a Russian prose-poet who came to Grinnell yesterday as part of the Writers@Grinnell Program. His works include Dancing in Odessa and Deaf Republic. Kaminsky immigrated from the U.S.S.R at the age of 16 and was granted asylum with his family; his works are strongly influenced by his Russian background, although he writes in English. He currently teaches poetry and literary translation classes at San Diego State University.

You write in English even though Russian is your first language. How do you think that affects your work—do you think in English as you write, or try to translate Russian thoughts into the different language?

That would be too complicated. I’m a simple person. I write in English. I like English—it’s a beautiful language. Russian literature is very different from English literature, simply because Russian literature is much younger. Pushkin, the grandfather of Russian literature, was writing in 1824. Byron was dead by 1824. Shakespeare was way dead by 1824. So you see here how much younger the Russian literary tradition is. So, it would be kind of … anthropologically impossible to think in Russian and write in English simply because English literature and Russian literature have very different standards.

Could you tell me more about when you first started writing in English?

I just have to write in a language with which I can go out, bicycle to the market, and hear people speak around me in it. For me, life is not an imitation of art and art is not an imitation of life. Language has to be around me all the time for me to write in it. So, I didn’t choose to write in it. I just had to write in it because that was the language that I was living in. I found English beautiful because … I heard people speaking it. And people are beautiful. I love Russian language and I love Russian literature. But it was not a daily part of my life anymore. And that may or may not be a good thing, but that’s the life I have.

What is it about your homeland that constantly inspires you to write about it?

I don’t write about my homeland. I write about my childhood.

Have you written about San Diego, or any of the cities you’ve lived in America?

Yes, I have one poem where I write explicitly about the United States. It’s called “We Lived Happily During the War.” That would be because we live in a country that bombs other people and laugh about it.

I was doing some research and I noticed you work to help disadvantaged people with their legal problems. How did you first get involved and why are you passionate about it?

Well, I was living in Russia. I left when I was 16. There was a propaganda program on Saturday mornings. Saturday morning is when they would show some of the most fun TV so everybody would watch it to be able to get to the good stuff. To be able to get to the good stuff, you had to get through a lot of scrap. And one thing that kept appearing over and over was how many people there were in the United States. Now, being a teenager in Russia, we didn’t believe it for a second. We thought it was all made up—propaganda crap. And then I came to the United States and came to Bay Area in California … San Francisco. Have you ever been to San Francisco? There is a district right in the middle of San Francisco with a lot of homeless people. That was quite a revelation. The kind of law I’ve worked with in the past is public interest stuff—legal aid—that tries to deal with some of those things. That’s what I thought was interesting to do.

And you’ve managed to do this while teaching?

I don’t do it anymore because there’s been new governor in California from about eight years ago. He’s also known as a bodybuilder.

(Laughs) Yes, I think I’ve heard of him.

But once he got that position, he was not very nice to legal aid, so a lot of jobs got cut. Now, the fact that I lost mine was not a big tragedy. But other people were … if you think about the Civil Rights Movement, the best and brightest wanted to retire in the Bay Area so they went to work there. And it was really tragic to see how Republican “reforms” put a lot of important advocates out of their jobs. I was fine. I just got a teaching job—a paid position. I like it. I would do it for free, but I didn’t tell them that. But that was the dilemma that I got to see in the early 2000s in the Bay Area.

The Jerusalem Post has written of your poetry: “[it] feels like it belongs to Russian immigrant dreamers, American tourists and the millions who perished in the Holocaust and Stalin’s purges, all at once.” Who do you feel like your audience is? Who do you imagine you are writing to?

I try not to write for an audience. My audience is that of dead poets—poets who I love and steal from. I write to please them. If I can please a poet who has pleased me, I am happy. Because if you write for an audience, you’re probably not going to succeed. Because you will limit yourself to a specific audience. How can you possibly know how a man a hundred years from now will be like? We don’t even know how an audience a year from now will be like—what kind of iPhone are they going to be using, you know? I don’t see the need to write for other people. Write for … God inside of you. Whatever it is that makes you want to breathe, want to kiss a girl, be alive at this point … that’s what you want to write about.

What advice would you give to aspiring young writers?

Read. Read all the time. You must read a minimum of thirty books a semester. If you read a minimum of thirty books of poetry a semester, you’re probably going to be okay. Also, fall in love with your language. My experience is with people who say, “I have important things to say. I need to write them down” are probably not going to be great poets. People who say, “I love the English language and I want to play with its words for the rest of my life” are going to be poets.

Can you expand on the difference between those two?

Yes. Somebody who says, “I have something important to say” will say it and have nothing else to say. Somebody who says, “I love words” will always have something to do. The biggest luxury in this country is to do something you love and get paid for it. Most people in this country work 9 to 5, just to make a living, but not because they love what they are doing. Be a poet because that’s what you love. If you love it and have fun with the language, then you’ll probably enjoy it for the rest of your life. And if you don’t, then do something you love.

So, you do you really recommend reading thirty books per semester?

It’s not that much. Think about it this way—don’t put it on tape or they will laugh at me. Put a book by your bed stand and a book in the bathroom … well, you live in a dorm, so that might be hard. … But by your bed stand, put a great poet, someone you really want to read, really want to know everything about: Emily Dickinson, Alan Ginsberg, whoever it is that you really want to read. And change that poet every two months. So you become a master of that great poet.

In two months, you can really dive into it. And in the bathroom, put a contemporary book. Those books are short, like forty pages, I would say. And change that book once a week. And I guarantee you, if you just read half an hour before you go to sleep, and whatever time you spend in the bathroom, you’re going to be reading without even noticing. And make sure you write in your books. Make it a mission to write in your books—underline your favorite lines, imitate your favorite lines, you know? And that way, you’ll be in conversation with great writers.