History Takeover: Grinnell as a refuge from WWII Japanese internment camps

Contributed by Grinnell College Archives

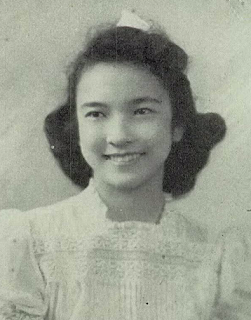

Barbara Takahashi `42 was one of the first three Japanese-American students to arrive on Grinnell’s campus near the beginning of WWII.

April 17, 2023

2023 Iowa College Media Association award winner, Third Place – Best Print/Online Features Reporting

On May 5, 1942 — as the United States entrenched itself in World War II, as rations spread and as public opinion searched furiously for a scapegoat — the Scarlet & Black ran a four-word headline — “Japanese Students Expected Here.”

In light of spiraling racial prejudice, the announcement signaled uncertainty about the safety of the forthcoming students. Yet, it also suggested hope — the newcomers, all Japanese-Americans from the West Coast, would have been taken “to concentration camps unless they left the coast by the end of this week.” For the three students mentioned in the article, education in the unfamiliar, potentially hostile Iowan prairie remained the only alternative to incarceration.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt had signed Executive Order 9066 three months earlier. This order gave the Secretary of War power to “prescribe military areas” on American soil — in other words, to expel civilians from their homes. In practice, the military removed Japanese-Americans living on the West Coast and forced them into “relocation camps.” The U.S. government justified this incarceration with the unfounded, racist assumption that Japanese-Americans would collaborate with Japan during the war.

The executive order spurred civil rights groups into action. The American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), a Quaker organization, secured a legal carve-out for college students to attend classes inland. According to Daniel Kaiser, professor emeritus of history, Joseph Conard `35 was a “local official” for the AFSC whose uncle, Henry Conard, served as Grinnell’s dean of faculty. The younger Conard urged his uncle to work with the AFSC and accept a limited number of high-achieving Japanese-American students. Henry Conard agreed.

So on May 8, Barbara Takahashi, William Kiyasu and Akiko Hosoi arrived at the Grinnell train depot. Hisaji Sakai disembarked at 3:00 a.m. two days later. He would later remember that “the entire freshman class was at the station to welcome [him].”

Living in an environment with virtually no other Japanese-Americans, these students experienced a blend of hospitality, well-intentioned ignorance and outright racism. Laura Ng, professor of anthropology, who researched an oral history about relocated Japanese-American students when obtaining her master’s degree, described the promise and precarity of the situation. While most participants were “really grateful” and “eager to continue their education,” many dropped out. Financial concerns motivated some. Others, Ng continued, struggled with the “onus put on them to show that they were integrating into society.” Indeed, the AFSC encouraged Japanese-American students to avoid congregating with other participants in order to foster the image of racial integration.

The country as a whole broadly supported Executive Order 9066. William Kiyasu `44 remembered being advised “not to enter town on weekend nights” for fear of violence from townspeople. Kiyasu remarked that after one ugly encounter, “it was a good thing [he] had a bike.”

Meanwhile, other Grinnell students welcomed the newcomers with open arms. George Carroll `02 spoke with several of the participants in his 2002 research project, “Japanese-American Student Relocation: The Grinnell College Experience.” None recounted any moments of blatant prejudice from Grinnell students.

However, the relative warmth of Grinnell’s reception comes with a caveat — it was still the U.S. in the 1940s. For instance, Conard heralded the incoming students as “the superior type,” possessing “the refined grace of the true Japanese.” Later, when the Iowa Senate proposed preventing Japanese-American students from attending college in Iowa, the S&B ran an editorial in protest. The article offered some genuine defenses of their classmates, noting that each Japanese-American student had recently made the president’s honor roll. Yet it also argued that concentration camps would make students “conscious of their race,” and that Grinnell students would prefer remaining ignorant of race.

The U.S. government closed the last concentration camps in 1946. Over those 4 years, Kaiser found that at least 13 students escaped imprisonment by enrolling at the College, including 6 who graduated. After that, Asian-American student enrollment plummeted for several decades. These students’ stories grew obscure and unknown to most Grinnell College students.

Who decides which stories are amplified and which stories gather cobwebs? In this case, only a few sources directly talk about Grinnell’s experience during the war. The most comprehensive source comes from a student, Carroll, who had a personal interest as both a grandchild of concentration camp victims and a Grinnell College history major. Ng had already completed graduate-level research on the topic before working at the College. Kaiser was inspired by Dan Ogata, a local Presbyterian pastor of Japanese descent. None of them encountered the story as a well-known fact already enshrined in the collective memory.

The next step, then, is to reinforce the legacy of these students, to make visible their successes and sacrifices. As Ng declared, “Grinnell should be proud of their involvement, but let’s tell the full story.”

Guy Scandlen • Apr 30, 2023 at 11:42 pm

Thank you for posting this story and the research.

Guy Scandlen

Chiang Mai

Thailand