A big part of coming to college is learning how to balance classes, extracurriculars, a social life and for some, a job. Although school is all students’ priority, many students also prioritize work on and off campus in order to pay for living expenses. There are numerous options for students to choose from, including on campus employment like Dining Services and off campus work, like Prairie Canary.

About half of Grinnellians have clocked in at a regular job on campus this semester. An estimated 800 students have logged more than ten hours since the beginning of the semester, according to Mark Watts, Human Resources Training and Student Smployment Coordinator. Another 140 have worked less than ten hours and are not considered regular workers.

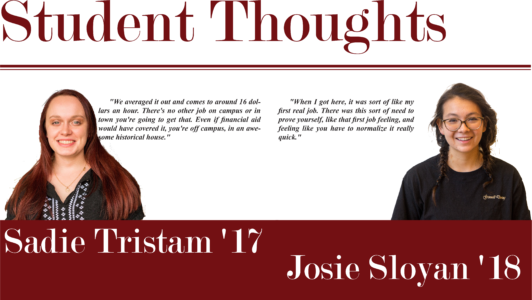

Josie Sloyan ’18 had her first “real” job upon arriving on campus as a first-year.

“There was this sort of need to prove yourself, like that first job feeling and feeling like you have to normalize it really quick,” she said.

Sloyan notes a difference between the daily lives of students who work and students who don’t work.

“It’s going to affect the way that you go about your day and how you’re allotting your time and what you’re doing with that time,” Sloyan said. “I think when you normalize it … it’s always really jarring to hear people say that they don’t work. I think it does add a lot of stress in your day. People don’t really think about it. They’re just like, ‘yeah this is the week.’”

Some on campus jobs are not well known — only select people know they even exist. Ryan Betters ’18 is an assistant animal technician for animals in the basement of Noyce. He takes care of rodents — the psychology mice and rats and biology mice — and sometimes, he takes care of two species of frogs, lizards, cockroaches, snails and minnows.

Each day, Betters checks animal welfare, food and water levels, cage cleanliness and overall animal well-being. He works around 12 hours per week, but he is able to pick his hours.

“You need to go in every day, but you can go in at any point,” Betters said. “I like working alone; I’m usually the only person down there.”

This job requires an employee who is responsible and reliable. Betters said that in the past, there has been a high turnover rate for this job because it only takes one mistake to be let go.

“There are animals that were direct results of professors’ grants. Those grants are reliant on these animals being taken care of,” Betters said.

Other jobs are still not well known but perhaps enjoy more company, rather than to those who spend time perusing Noyce. Sadie Tristam ’17 is a Grinnell House monitor and welcomes guests to campus. Grinnell House was constructed in 1917 and was the home to all of the college’s presidents from 1917 to 1961. These days, the “handsome Georgian building, an almost pure example of that style,” hosts visitors to Grinnell, according to the College’s website. Some past guests have included Presidents Harry Truman and Dwight Eisenhower.

According to Tristam, being a Grinnell House monitor is one of the best jobs on campus — especially for students who have to work off campus to supplement their incomes. The monitors live in Grinnell House, and they need to be on the first floor of the house for 20 hours each week. Sometimes they may need to do some cleaning or take out the trash, but they often have free time.

“You’re [able to] get your homework done in the time that you’re scheduled to work,” Tristam said. “If a guest comes in, you greet them — it’s a great chance for networking too because the people that stay there are usually alums or people who are speaking here. … It’s basically just being there.”

And then there are jobs that are visible, but have a small staff that’s able to do meaningful work. Christine Hood ’17 is an executive co-coordinator for the Wellness Lounge. She started at the Wellness Lounge as a board member her first year, after realizing that her job swiping cards at the Bear offered less fulfillment than the Wellness Lounge position could.

“I personally have had a lot of experience with mental health throughout my family, my friends, my own personal experiences,” Hood said. “I’ve found that when you actually do take time for yourself it usually does help.”

The Wellness Lounge hosts study breaks and events, often coordinating with other groups on campus. One weekly event is Tea Time, which happens every Tuesday with free tea, brewing and sometimes extra small events — for example this past week lounge leaders organized a terrarium-making workshop.

At the Wellness Lounge, Hood works around 7-10 hours per week. However, she is able to somewhat make her own schedule, so it varies.

Often, students opt to work off campus instead of settling only for on-campus jobs. A student’s time working off campus does not count toward the 20 hours per week limit on work at the college itself.

Prairie Canary, one of the hip restaurants in town, often hires college students. Currently, around 20 out of the 40 workers at Prairie are students. Students are requested to be available for five shifts and work a minimum of three, which comes out to a minimum of about 12 hours per week.

“We do hiring all year long, depending on how many staff members we have and how many people we’re losing,” said Tyler Zhorne, front of house manager of Prairie. “We’re super flexible. For example, I’m on salary, so if we were short staffed on servers, I’ll just work server so that we’re covered on all bases.”

For employers, there are valuable aspects as well as challenges to employing students, who often prioritize school work and class schedules. The College’s libraries are dependent on students, and sometimes students progress in their library careers to take on more advanced roles.

“Some of our students are driven to become library professionals or archivists. So they’re dedicated; they’re here 10 hours, but they’re learning every time they’re working, too. Many of them offer really exceptional service by the time they’re juniors of seniors,” said Mark Christel, Librarian of the College.

Not only are the libraries dependent on students, however, but the libraries also intend to positively impact students in their careers and futures in library-related work.

“I don’t walk in the door on day one and know everything I need to know to be a good library director. I need to keep learning every day on the job. I hope we’re working to scaffold things so that over a career or three or four years, student workers are learning new skills, learning interesting things,” Christel said.

At the college’s libraries, students are limited to working 10 hours a week. Although such a limit makes it so many students need to be hired, the training and investment in a full-time staff member is much greater than for additional students.

“Money wise, we employ a lot of students because we don’t have to provide benefits, which is a substantial cost,” said Michele Behounek, Manager of Access Services. “Our student staff is essential for the day-to-day operations — we couldn’t stay open [without them] because we’re open 110 hours a week between the two libraries.”

Some of these workers have to work on campus as part of their financial aid package. The College cannot estimate an accurate number of student workers that work as part of their financial aid package, because some students choose not to have a job. However, a lot of students who work do so to pay part of their tuition through work-study.

If a student works eight or nine hours a week, that student can expect to earn about 2,200 dollars during the academic year, according to the College’s website. This number is a typical expectation of work-study financial aid in terms of how much a student will contribute to their tuition through working on campus per year.

This eight to nine hours per week expectation stands if the student puts 100 percent of their earnings towards their work-study. Students do not have to put all of the money that they earn towards their work-study balance. They can opt for a certain percentage of their paycheck to go towards their tuition with the rest to their pocket, or for 100 percent of their earnings to go straight to the Office of Financial Aid and towards their tuition. Many students on campus work more than the eight to nine hours a week, in order to help support themselves as well as pay towards their tuition.

“Federal work study usually goes straight to the school. It’s hard … for you to earn any income when you’re on a federal work study, you usually have to be working more than 20 hours, especially with the pay grade,” Hood said.

One of these student-workers is Sloyan, who works at the Grill and with catering. She works eight hours of work-study per week, as well as four to six hours per week off campus at Pagliai’s, a restaurant in town. All of her on campus earnings go straight to tuition, as do a portion of her off campus earnings.

Isaac Mielke ’18, a mentor in the Economics Department and a tutor in the Math Lab, works nine hours a week as part of work-study. He also sees a difference in his days compared to those who do not work. “I just have less free time … probably [have more stress].”

For many on campus, working and contributing this way towards tuition is just part of the everyday grind, the same as going to class and heading to Burling to do homework.

“I feel like as a work-study student, you really don’t think about what it’s like to not be one,” Sloyan said. “It’s just sort of a matter of course.”

Dining Hall Union Update

The Union of Grinnell Student Dining Workers (UGSDW) became one of the first unions of undergraduate employees in the nation to ratify a contract with a private institution when they voted to instate a new contract last Tuesday, Sept. 27. The contract, which was settled upon after their bargaining team met with the College, was approved in a 33 to one secret ballot.

The contract includes an experienced pay package. The base wage for all Dining Hall workers was raised from 8.50 dollars per hour to 9.50 dollars per hour, with a 25 cents raise for every 110 hours worked and a maximum wage of 10 dollars per hour. Student leaders start with a base wage of 10 dollars per hour, and can earn up to 10.75 dollars per hour based on hours work in a similar scale.

There were few points of disagreement between the Union and the College, but the disagreements that did arise were worked through. “By listening to both sides, we were able to meet and sometimes change how we looked at things,” said Union President Cory McCartan ’19.

Sticking points included how to notify new hires of the existence of the Union and wages. “The College said that really, the problem comes down to students working one shift a week, and it’s barely worth the money to train them, … so we said ok, if we can go down to a lower base wage and have this larger experience pay package, that could work really well for everybody involved. It was definitely a cooperative process.”

Going forward, the Union is focusing on the practical implementation of the contract and getting more Union members. “Our first priority is making sure that the contract is implemented and get more people signed up and part of the union,” said McCartan.

There was a lot of controversy surrounding the creation of the Union last year. Many students felt that it should include the career staff and non-student workers of the Dining Hall.

“It’s against federal labor law to have people who are supervisors and have the power to hire and fire people in the same bargaining unit as the people that they are in charge of hiring and firing, because then there’s worry that they would use their power to influence the union. But as I understand it, the Marketplace supervisors do not directly supervise or sort of have complete firing and hiring decisions over the career staff,” McCartan said.

Regardless, McCartan said that the UGSDW does not have the resources to appropriately represent full-time, non-student workers. “For career staff, if they hypothetically went down the road of wanting to unionize, it’s not unlikely that they could face a lot harsher resistance,” McCartan said. “We wouldn’t feel very comfortable trying to protect and help them unionize if we couldn’t offer the same sort of support that a more traditional union could.”

The new contract does include a no-strike clause, which some may see as taking away leverage from the Union that it would potentially need. However, McCartan said that no-strike clauses are commonplace, and that a binding arbitration process is included in the contract, should disputes arise.

The arbitration process will allow for the dispelling of conflict. “The arbitrator is just supposed to look at the contract and labor law and decide what the fairest and right legal outcome is,” McCartan said. “The arbitration panel is drawn from elected student government and faculty members.”

The Union and the College are currently compiling a list of 20 potential panel members. The list, comprised of faculty and Student Government Association elected officials, will be deemed mutually acceptable by the College and the Union. If a dispute should arise, and the parties go into binding arbitration, five members will be chosen randomly from the list. Then each side will strike one name from the five, and a panel of three members will hold a hearing.

McCartan sees the Union as a positive thing for students. “From our point of view we think it’s a pretty good deal to join the Union. You have the chance to vote on Union issues, you don’t have to pay anything,” McCartan said. “We’re confident that if we have more outreach, we’ll get more members.”