On Monday, Nov. 11, the Grinnell College Rosenfield Program hosted Jessica Calarco, sociologist and professor of sociology at University of Wisconsin-Madison, on campus to speak about her new book, Holding It Together: How Women Became America’s Safety Net. The 4 p.m. book talk was held in JRC room 101, with about 75 people in attendance, and was followed by an open invite dinner at 6:00 p.m., where a group of over 10 students, faculty and staff continued the conversation with Calarco.

Calarco began her talk by connecting the results of the 2024 election with the findings of her research. “I’m grateful to be here to unpack this with all of you, and I hope that today’s talk will have some resonance and some relevance, especially making sense of how we got here and even maybe where we go from here,” she said.

Calarco’s book draws on research conducted by herself and her research team, who conducted “1,110 surveys with 374 participants and 312 in-depth interviews,” according to the book’s introduction. The research also includes two national surveys of about 2,000 families each as well as historical and media analyses.

“The story here is that we force women to hold it together for their families, for their communities, and really for the good of the U.S. economy as a whole,” said Calarco.

She told the story of a woman named Brooke, a pseudonym, who participated in her research. Brooke accidentally became pregnant in college. Her parents, white evangelical Christians, convinced her to keep the baby, so she had to drop out of college to take care of the baby and make ends meet.

“Brooke ended up moving with her son into a shelter and applying for welfare,” said Calarco. “Welfare, though, as some of you may know, came with work requirements, so she had to essentially take the first job that she could find, and she started with a minimum wage part time job in retail.”

Her first full-time job was at a childcare center, and though she enjoyed the work, it did not pay well and did not come with benefits that could give Brooke security. After a few years, Brooke got married, thinking having another parent could give her time to go back to college.

“But, she ended up getting pregnant again, and her husband and his family persuaded her to drop out of the workforce and to become a stay-at-home mom, even though her husband was only making about $30,000 a year as an auto mechanic,” said Calarco.

Calarco said that Brooke’s experience highlights why young women are concerned about political attacks on reproductive freedom. “Brooke’s story also shows us how the U.S. forces women to fill the gaps in our economy and in our social safety nets by essentially trapping them in either motherhood or other types of underpaid or unpaid caregiving roles and then leaving them with nowhere to turn for support when they need it,” said Calarco.

Calarco also showed that Brooke’s story is not unique. “In the U.S., for example, women do almost twice as much unpaid caregiving labor as men do, caring for children and the sick and the elderly and their families and their communities,” she said. “And women, disproportionately women of color, also hold the vast majority of jobs in the in the care sector, jobs in fields like childcare and home health care, which are among the lowest paid jobs in The U.S. economy as a whole.”

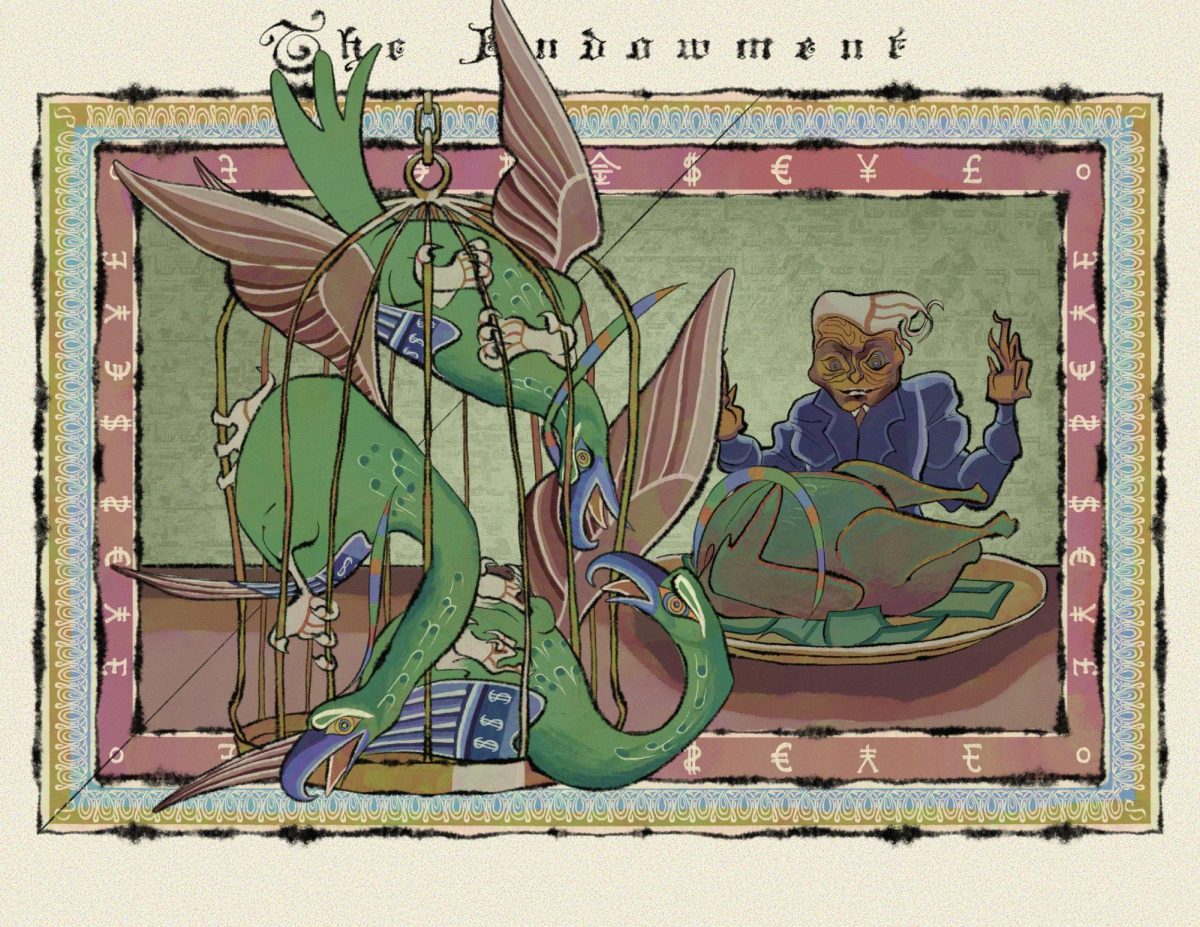

While Calarco acknowledged that much of this problem stems from long-standing gender roles and institutional sexism, she also emphasized the role of neoliberal policies in the United States in creating and exacerbating these difficult realities for so many women and families. Calarco points to what she calls the “myth of a DIY [do it yourself] society,” the idea pushed in response to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Depression-era New Deal “that we don’t need a social safety net or the kinds of taxes, particularly on wealthy people or corporations, to pay for it, because people can take care of themselves and essentially pull themselves up by their own bootstraps instead,” she said. “Wealthy business owners and their friends and cronies were able to persuade Americans to believe this neoliberal ideology, in part by launching massive propaganda campaigns.”

Calarco gave the example of Sweden, a country that, according to Calarco, has made much bigger investments in comparison to the U.S. in universal social safety net programming, including universal childcare and guaranteed paid family leave. “And in the context of those kinds of investments, we see that women in particular are doing better — we see higher levels of maternal labor force participation, lower levels of maternal mortality, lower levels of postpartum depression, smaller wage gaps between mothers and fathers and a smaller number of families with children that are living below the poverty line,” she said.

After the presentation, audience members were given the chance to ask Calarco questions. “I was wondering if you found effective ways to persuade skeptics,” Bella Steward `25 asked. “One of the best ways that research suggests to change people’s minds is to change the structures around them,” Calarco responded. She said that in other countries when social safety net policies like universal paid family leave are put in place, “you do start to not only see men engaging more in care responsibilities and participating more equally at home, but you also start to see attitudes change in the process, too. And so essentially, I think it suggests that attitudes are often a product of the structures that we are part of.”