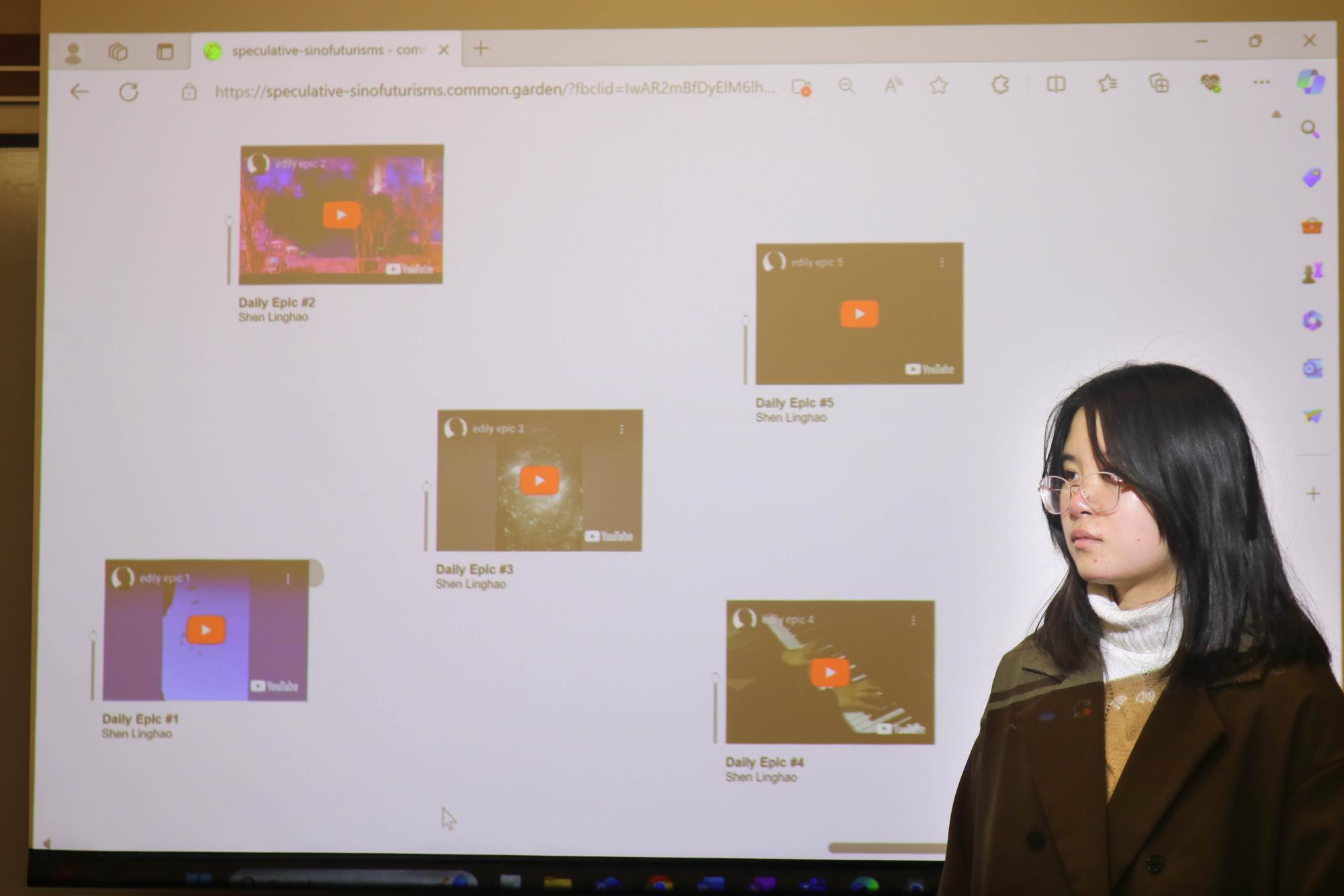

Amy Kan `27 hosted a curatorial talk on her independent digital exhibition titled “Speculative Sinofuturisms.” Attendees at the Grinnell College Museum of Art on Thursday, Jan. 22 paid rapt attention as Kan delved into the processes behind her project and larger reflections on the contemporary art movement.

Kan’s curatorial project is one of many from around the world hosted in the current run of “The Wrong Biennale,” an online showcase event run by creative agency TheWrong Studio.

According to Kan, she was still a senior in high school when she came across TheWrong’s open call for the 2023-2024 run of the biennale. Having just submitted her college applications, she said that boredom and “naive ambition” prompted her to submit a curation centered around Sinofuturism.

The Sinofuturism movement is credited to a 2016 video essay by multimedia artist Lawrence Lek titled “Sinofuturism (1839 – 2046 AD),” and it is about critiquing “the present-day dilemmas of China and the people of its diaspora”’ through fusions of “science fiction, documentary melodrama, social realism and Chinese cosmologies.”

To that effect, “Speculative Sinofuturisms” features artworks from over 20 young Chinese artists encompassing the experimental and bizarre. In developing the direction of the curation, Kan said she turned the word “Sinofuturism” into a plural term to emphasize themes of “temporality, multifacetedness and open-endedness.”

Kan explained that while she had a longstanding interest in abstract expressionism, she was particularly drawn to Sinofuturism because of her heritage as part of the Chinese diaspora.

“I wanted to think about something that felt closer to my reality,” she said.

At the curatorial talk, Kan spoke on the influences of the project on her own creative processes.

“I was thinking about finding a place for voices of artists that have traditionally not been highly valued in the Western art history canon,” she said. “It has impacted how I think about exhibitions and how we experience museum spaces and galleries.”

Kan said she gathered the works by finding artists’ Instagrams and emails. She split the pieces into a broad range of themes that ranged from “Nature,” to “Personhood,” to “Damocles’ Sword.”

“The way I parsed through the themes that I saw obviously reflect something about my lived experience,” she said.

Kan said that she was shocked that “so many artists trusted me enough to partake in this,” since she had no prior curatorial experience

Gangao Lang, a photographer and model featured in the exhibition, said that she had been glad to participate because it was the first time she had seen someone work on such a theme.

“I think it’s very important to work together with people in the same generation,” Lang said, adding that Kan was the youngest curator she had ever met. “Her perspective was very unique.”

Yasmine Anlan Huang, another featured artist, praised Kan’s work ethic for being “more professional than some established curators.”

“In the beginning, I was afraid that the term ‘Sinofuturism’ was too generic,” said Huang. “But after I saw the list of artists and the way she composed everything, I felt there was potential.”

Both Lang’s and Huang’s exhibited pieces are on the consequences of embracing rapid technological development.

“Things are developing so fast that we don’t know the direction. We just know that we’re rolling on and on,” said Lang, whose video work “Model N” depicted a 3D model of a wheel in constant motion, exploring themes of duality and centralization.

For Huang, “Illogical Innocence: How to be a Former Idol” is a performance piece that shows her pretending to be an idol on Tinder as a commentary on the increasing digitalization and commercialization of girls and young women in East Asia.

“This exchange of love really fascinates me,” said Huang. “You, as the ordinary girl, can also be the star, the hope of other people.”

At the museum, Kan played videos of Lang and Huang discussing the meanings of their pieces because, to her, it had been important that “the artists be heard from directly,” as she did not feel experienced enough to be the sole authority on interpreting their works.

Kan said she had been communicating with the museum on the possibility of hosting an event even before her arrival on campus in the fall 2023 semester.

Tilly Woodward, the museum’s curator of academic and community outreach, worked with Kan on the logistics of the event, such as its structure, target audience and publicization. She wrote in an email to The S&B that it was “very rare” for incoming first years to have already independently executed entire curatorial projects on such an international scale.

“I was impressed with her ambition and professionalism,” Woodward wrote. “Amy was a delight to work with.”

However, Kan has already identified areas of improvement, saying that she felt her themes had not been consistent. “I’m not sure how much I agree with the way I grouped the works,” she said.

She added that she struggled to translate the works’ performatory aspects into virtual formats, although in retrospect, “It worked out nicely.” She expressed hopes to continue working with the College on future curations and take art history courses on museum studies and exhibition.

For all the complex, avant-garde works chosen for the exhibition, Kan expressed belief that the core of the Sinofuturism movement was, simply, hope.

“There is something inherently hopeful about moving forward,” she said. “You don’t do that unless you think there’s something more in the future. You have to have at least some optimism for what’s coming, some light to strive towards.”

“Speculative Sinofuturisms” will run on The Wrong Biennale until March 31.