Applicants to Grinnell College will continue to decide whether they submit standardized test scores with their application.

The test-optional policy will be in place until fall 2026, at which point the College will re-evaluate the policy and determine whether or not to continue with it in future years, according to Joe Bagnoli, dean of admissions and financial aid and vice president of enrollment.

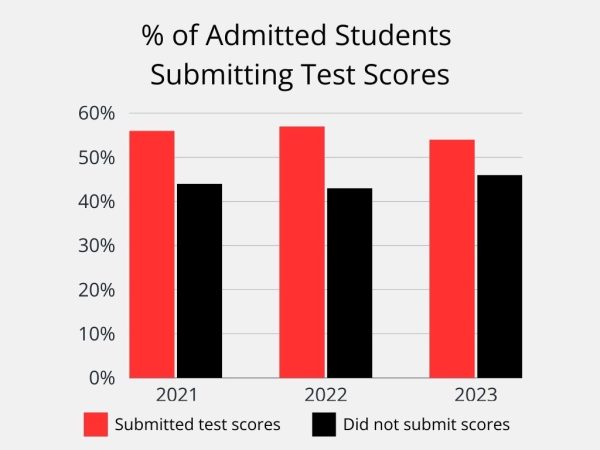

Grinnell applicants who submitted test scores were on average 11 percentage points more likely to be admitted over the past three years than students who did not submit scores, based on data shared with the S&B by Bagnoli. In 2023, students who submitted test scores made up 41 percent of the applicant pool but constituted 54 percent of the admitted students and 51 percent of the enrolled students.

“We believe it’s more important to consider what happened over a four-year high school period than in a four-hour exam period,” Bagnoli said, summarizing the transition to a test-optional policy.

The College instated the test-optional policy in June 2020 following the closure of many testing sites due to the COVID-19 pandemic. A one-year extension was granted for the 2021-2022 academic year, allowing the Admission and Student Financial Aid Committee (ASFAC) to evaluate the initial effects of the policy. ASFAC, which includes faculty, students and administrative leadership, ultimately recommended a four-year adoption, which was approved by President Anne Harris in 2022.

Referencing one impact of the policy at Grinnell, Bagnoli said, “With the introduction of test-optional admissions, we found that many more historically underrepresented students were in our applicant pool than had been prior to the adoption.”

Maria Rossi `25 said that she thinks the ACT and SAT tend to unfairly advantage wealthy students who can afford to take the test numerous times and receive tutoring. “I had two years of test prep in high school, but not every applicant can do that,” Rossi said. “Standardized testing in general is not the best way to get the most accurate representation of an applicant.”

Removing test scores from the admissions equation, however, means that other application materials must play a more prominent role. At Grinnell, placing an applicant within the unique context of their high school is increasingly important, according to Bagnoli. This requires admissions counselors to analyze an applicant’s “academic initiative” by looking at measures such as GPA, academic rigor, extracurriculars, recommendation letters and demonstrated interest.

Some studies have found that test-optional policies may not actually be increasing diversity on campuses, contrary to what many colleges argue. One recent study of 99 private undergraduate institutions found that test-optional policies increased the share of Black, Latino and Native American students by only one percentage point.

Even though the pool of diverse applicants may increase after a college becomes test-optional, these students are not necessarily being accepted at an increased rate, a trend Bagnoli said may worsen due to the end of race-conscious admissions.

Test-optional policies also tend to disproportionately benefit women, who tend to have higher grades relative to their test scores. Men, in contrast, tend to receive lower grades relative to their test scores.

Additional studies indicate that colleges that use standardized criteria more heavily in admissions are less likely to give preference to wealthy applicants. This bias in favor of wealthy students tends to be even more pronounced in measures such as essays, recommendations, advanced courses and extracurriculars.

The S&B requested data on the number of applicants and admitted students by race, income and gender before and after the test-optional policy was implemented. The Admissions Office was not able to provide this “disaggregated data” because “the size of our student body makes it too easy to draw conclusions that can affect individuals,” Bagnoli wrote in an email to the S&B.

When asked whether bias may be more pronounced in the Grinnell admissions process since becoming test-optional, Bagnoli said that he has “not observed it anecdotally in the Grinnell context.”

“What I’ve observed in Grinnell is that our committee is less interested in reasons not to admit a student and more interested in reasons that a student might be viable,” he said.

Bagnoli also said that the Admissions Office has always weighed other factors more heavily than test scores.

“Tests played a much more modest part in our selection process before we were test-optional than most people assume,” he said.

Almond Heil `25 said that they submitted test scores to Grinnell, indicating that they made the decision after comparing their scores to the median scores of applicants.

The 50th percentile of test scores submitted to Grinnell in 2022 was 1460 composite for the SAT and 33 composite for the ACT. Grinnell’s website offers advice to applicants on what to consider when deciding whether to submit scores.

“I feel like I did a good job in my application depicting myself as someone who would fit well at Grinnell,” Heil said, explaining why “fit” could be an alternative predictor of students’ success during the admissions process. “My academics were not the main part of that depiction.”

ASFAC plans to examine the effects of the policy in fall 2026 before making a decision on whether to remain test-optional or reinstate a testing requirement. Bagnoli said that the decision will likely involve comparing GPA, graduation rates, outcomes and diversity between applicants who submit scores and those who do not.

“I think the jury’s still out a little bit in terms of what the end result will be,” Bagnoli said.