Faculty struggle to justify MAPs due to change in compensation

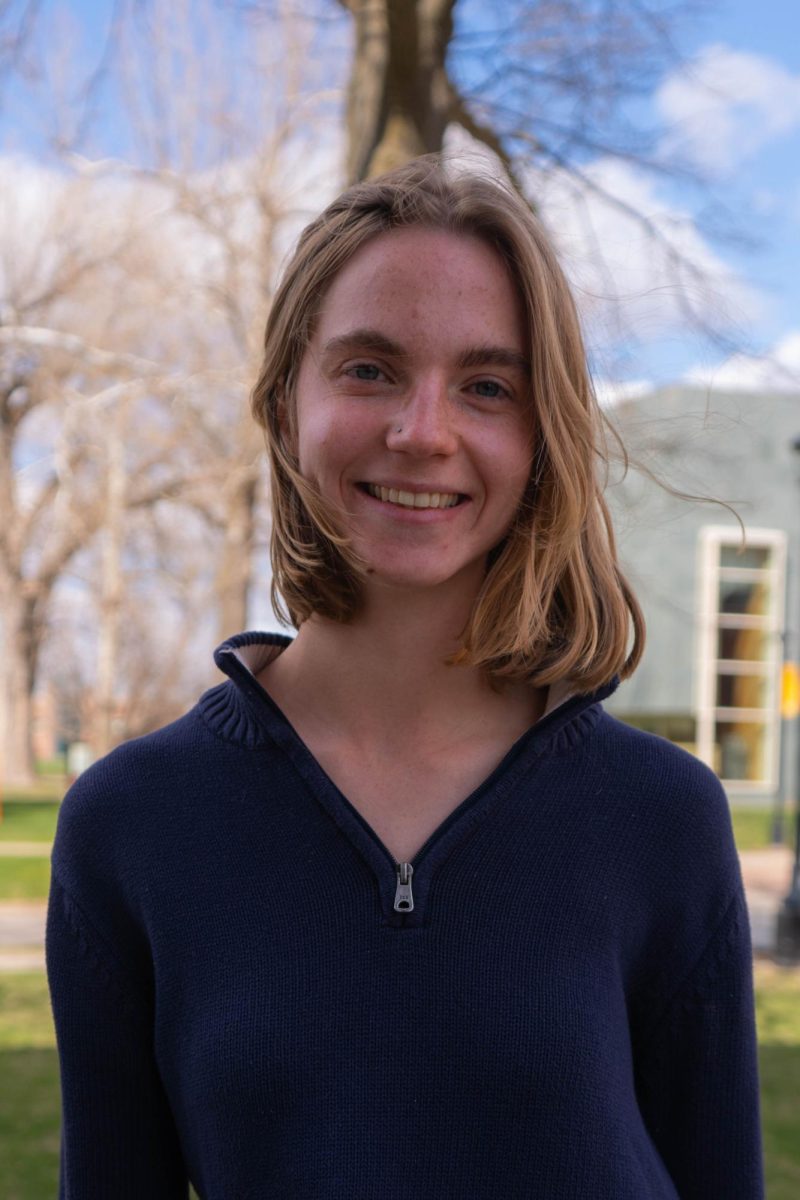

Lucy Polyak `23 directed a musical production for her MAP.

March 6, 2023

For Lucy Polyak `23 and Craig Quintero, professor of theatre, dance and performance studies, their Mentored Advanced Project (MAP) represented an opportunity to reignite a sense of belonging and community on campus post-pandemic. Given the chance to direct a production of “The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee”, Polyak described her project as a formative and meaningful capstone to her time as a student.

However, cases like Polyak’s have become less common as Grinnell faculty struggle to justify supervising MAPs during the semester due to a compensation policy from 2016.

The MAP program allows students to work on advanced projects for four, six or eight credits under the direct supervision of a chosen faculty member to gain research skills and hands-on experience in their field of interest.

A change in policy from 2016 no longer financially compensates professors for supervising MAPs during the semester. Michael Latham, former dean, said that they wanted to recruit a more robust faculty pool by making the College’s sabbatical policy more competitive with other schools through the reallocation of compensation for MAPs conducted during the semester. The current compensation model uses MAPs and other research programs to measure the professor’s work with student research as part of the application process for faculty sabbatical leave.

Due to these changes to the compensation model, faculty have found it harder to justify the extra labor of working with students on MAPs during the semester. Edward Cohn, professor of history and European studies, noted that this policy seemingly exists due to differing labor expectations. Students are given course credit for MAPs and complete those projects alongside their other classes, contrasting the apprenticeship style of research that occurs over the summer and necessitates a stipend.

“The idea is that that [summer stipend] should be enough to cover your expenses and not much more than that. Whether it works, though, in practice, I’m not completely sure,” Cohn said.

The previous compensation model allowed professors to receive payment for involvement in MAP research or convert that labor into course credit. A faculty member’s participation in six MAPs supplemented a class the professor would no longer have to teach the following semester. 12 MAPs could cover 2 courses from a faculty member’s annual contract, which allowed them to take a full-year paid sabbatical.

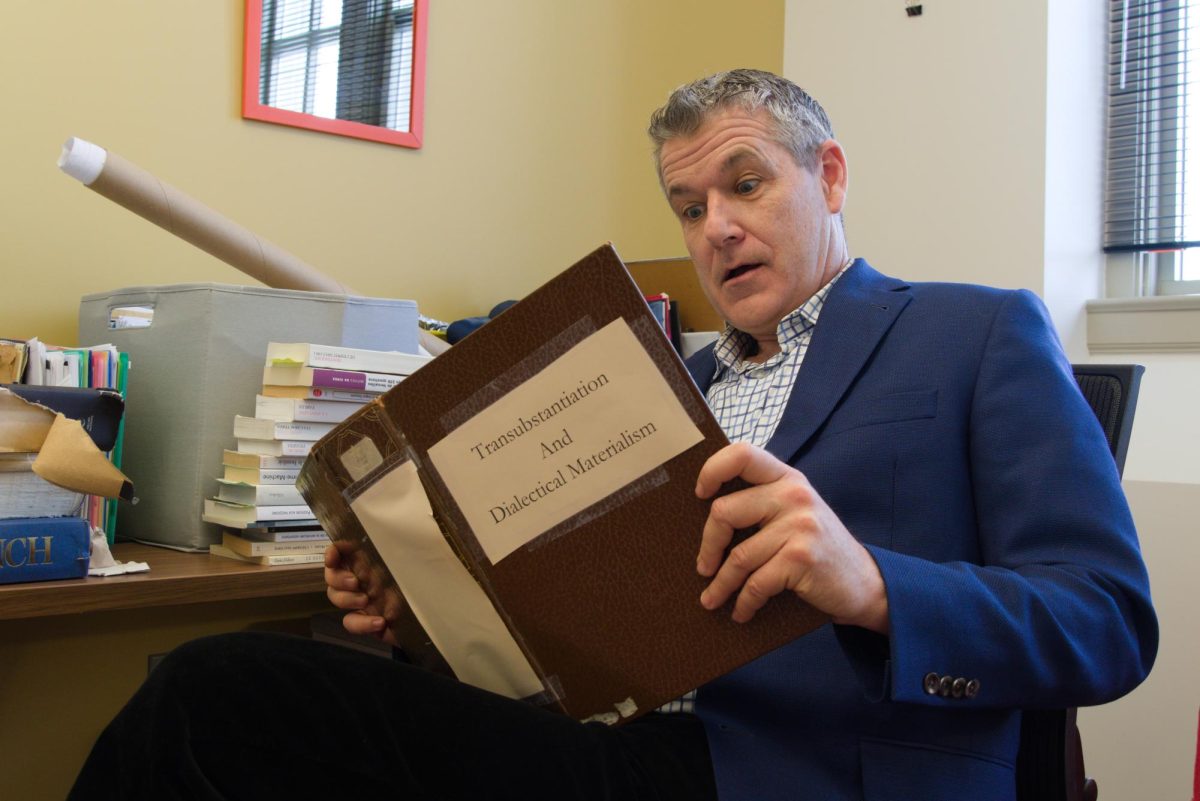

Andrea Tracy, professor of psychology, researches the neuroscience of ingestive behavior, and noted how assisting in student research can contribute heavily to a faculty member’s access to a full-year sabbatical.

“You’re supposed to demonstrate that you have done research with students,” Tracy said. “It doesn’t necessarily have to be MAPs, although MAPs are the easiest way to demonstrate that.”

The policies determining faculty MAP credits made it difficult to consistently plan for when professors would be leaving for their sabbatical, and the office of the registrar faced challenges planning upcoming semester courses. The transition from trading MAP credits for course releases happened in phases so that faculty could use their course releases or opt for payment. Cynthia Hanse, associate dean of the College, approves MAP applications and said that the lack of compensation is consistent with the College’s academic outcomes.

“Change is always hard. There were some individuals who definitely preferred the older model and others unhappy with that shift,” Hansen said. “I would say that it was a change that the institution needed to take.”

The current model imposes stricter limitations on the types of research available to students. Since applications require a relevant faculty member, students with novel research ideas that do not currently exist at the College are more likely to join a professor’s existing research instead. Karla Erickson, professor of sociology, notes that specialized mentorship in unfamiliar fields of study are typically more challenging to undertake during the academic year.

“I have students all the time who come to me with this great idea. There’s no way I can do that project with [students].” Erickson said. “The only way I’ve been able to find that works for me is if I can get a group of students to think on my own questions with me.”

These changes have also shifted the MAP application process and how faculty members recruit potential mentees. The science division recruits MAP applicants through a division-wide application process, where students can access summaries of existing research opportunities across the division and formally apply for a MAP. This system has also proven necessary for professors in other divisions, which has made the availability of MAPs more competitive for students.

“The only problem is that it’s uncompensated, so it’s mainly overtime,” Erickson said. “I can’t just do it out of the generosity of mine and then still find time to do my scholarship, so for me, my maps have to advance my own scholarship.”

Differences in access to funding resources can also present disparities in student opportunities. MAPs focusing on the social studies division and independent majors constituted 9 overall approved MAPs this semester, while 19 applications were geared toward the sciences.

MAPs in the STEM fields can currently access external grants funded by alumni donations, which allows the program’s operating budget to fund more MAPs outside of the program’’ operating budget. These grants, like the Cech Scholars program, are exclusively donated to support faculty-mentored summer research opportunities for specific groups like BIPOC students and first-generation students.

“It’s really uneven in any given year,” Erickson said. “Our most highly qualified social majors may not do a map just because it doesn’t line up or their professors are already pursuing something that didn’t interest them.”

“As opposed to just waiting for a MAP to appear, go for it.” Polyak said. “You have to create the opportunities that you want.”