Q&A: Professor John Garrison, English, on learning, growing and asking for help – and his newly announced Guggenheim award

April 20, 2021

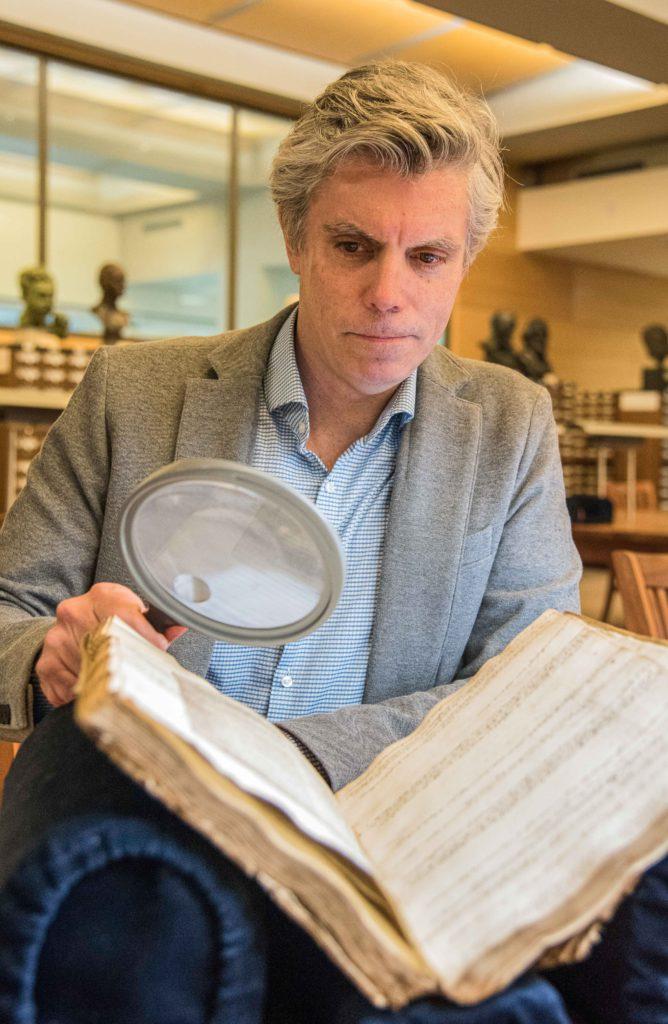

John Garrison, professor of English and the chair of peace and conflict studies, won the prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship on April 8, 2021, one of 184 artists, writers, scholars and scientists selected from a pool of almost 3,000 applicants. According to its website, the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation gives out grants to individuals who demonstrate “exceptional capacity for productive scholarship or exceptional creative ability in the arts.” Garrison’s fellowship falls under the category of English Literature, to support his work exploring desire and memory in Shakespeare’s poetry.

Professor Garrison obtained his undergraduate degree in English at UC Berkeley, and then worked as an AmeriCorps member at the San Francisco AIDS Foundation. He then worked for the Levi-Strauss Foundation, and moved to New York to work in the technology sector. In his early 30s, he went back to California, obtained his PhD at the University of California Davis, and became a professor at Carroll College. He began working at Grinnell College in 2017.

The S&B’s Lucia Cheng `23 met with Professor Garrison to chat about his life, the Guggenheim, and in particular, what it means to help people.

The following interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Garrison’s History

The S&B: How did you get started on the path you’re on now?

Garrison: Well, I grew up in Northern California. My dad was an engineering professor, and my mom worked for Planned Parenthood. That combination, to some extent, always inspired me to want to teach on the one hand but also to do work that can help other people out, that was community based, that met people in a moment where they really needed support.

I was brought up in this family that wasn’t defined by any one thing, where people were just thinking a lot about big ideas and literature, but also about how to give back and how to be there for people when they needed them.

How did you envision helping people back then?

Growing up as a gay man in the Bay Area in the late 80s, early 90s, I was surrounded by the HIV epidemic. My parents lived in a suburb of Berkeley, and growing up, our neighbor’s partner died of AIDS. And then our neighbor died of AIDS several years later. It was really close to home, even when I was in high school. Because of that, my initial instinct was to get involved in the HIV epidemic, and the particular job I was assigned to – with the AIDS Foundation – was to help train volunteers to answer calls in the California AIDS Hotline.

That helped me learn early on that helping people wasn’t just doing direct service. It was also about training and teaching other people how to help other people. I learned that I really loved being in front of people, teaching them different kinds of skills and sharing different kinds of information.

How do you think the AIDS crisis has shaped your worldview?

When I was in my early 20s, just the absolute best of people, most of them people that I knew, died. I knew some of the most amazing people you could ever imagine walking the face of the planet. And, you know, I could probably still list them today. They all died of HIV/AIDS.

What I really took away from that, and carried forward for the rest of my life, was that our moment in the world can be very fleeting. And we don’t know how long we’re going to be here. And on one hand, the best we can do is inspire others, as I was inspired by these people.

But also, what’s true is that you have to take risks and you have to take chances, in order to make sure that you’re living life to the fullest.

Is that still something that motivates you now at Grinnell?

One hundred percent. … The funny thing is: it’s worked out. In my late 20s, I gave up a really good job, and I moved to New York City with $300 in my bank account. And guess what? I found work. I found a job. I made friends. I got a cool apartment. And I ended up with a great career there and it was really exciting. But, I really wanted to become an English professor.

So, I just quit and went to grad school. If you’re gambling on being happier, then it’s worth it if you do the work. The path might be sort of rockier than you think, and you might have a lot of side roads getting there, but if there’s something you really, really want, if there’s a dream you have, then there are people around to help you get it. And a lot of what I learned was about asking for help.

Lessons of Help

… Going back to my early 20s, there was a whole group of people who taught me so much. For example, when I worked at the AIDS Foundation. When I look back on the fact that a lot of those folks were really in the last couple of years of their life, the fact that they took the time to teach me how to be a better person, to help me figure out how to be in the world, it’s so meaningful to me in terms of their generosity. That’s been true throughout my life.

The biggest lesson in my life is to learn to ask for help. It’s something that’s been a really hard lesson for me to learn. But a lot of the time, we don’t know how to help other people unless they tell us. And we need to be paying attention, to be aware of the times people have helped us…. If we look at our lives less as a genealogy of things that we’ve discovered and achieved, and more as a genealogy of “When have people helped me, and when have I helped someone else?” it keeps us more aware of other people, and from becoming too invested in our own success.

How do you see yourself as a person who is active, and chooses what to do with your life?

That question of, “To what extent can someone choose what happens in their life?” brings me back to the questions of social justice that started my whole career. All the while I’m talking about the adventures I’ve had … that comes with the shadow that a lot of people can’t make these choices about their life. And a lot of people don’t have access to this kind of education, financial freedoms, security, safety, health, that many of us do…. I really want to use what I gain from [the Guggenheim] to keep on doing social justice work in the classroom and elsewhere, in order to acknowledge those folks, and to think about ways they can be given more access to those freedoms.

As you’ve mentioned before, it’s like a gamble. We don’t know what the future will look like. Were you ever scared at all?

You know, it’s kind of like Bruce Banner in “The Avengers.” When they ask him, “How do you get angry in order to turn into the Hulk?” And he says, “The secret is: I’m always angry.” The reality is, for me, to have been fearless at different parts of my life, the secret is I was always very scared. In fact, I am always scared.

But I overcome that fear, because I feel like I owe it to myself to live the life I want to live.

His Research Now

How did you try to create a good learning environment for your students?

A lot of people in the early part of my career, when I was an undergraduate, really wanted to hear my ideas about things. At the time, I didn’t know what to make of that, because it set off all kinds of self-doubt. But it eventually transformed into confidence. I felt like I had ideas that were helpful to people.

So, rather than come to Grinnell like, “I have ideas that will help things,” I’ve been interested in paying that back, engaging in that same practice. I want to hear from students what they need. And in turn, I want to figure out how to support them and what to do for them.

I’m not some sort of super-individual-changemaker person. It’s more that I listen as carefully as I can, and figure out what I can do to help people meet their needs.

Why Shakespeare?

There’s something there that’s deeply mysterious to me. And there’s something about Shakespeare that makes people want to know what he’s all about and why it’s so important and why people are still talking about him. So, I want to explore that with people.

Really, really, really early on when I was at Berkeley, I had a question. I read Michel Foucault’s “History of Sexuality,” Volume One. There was a line in there that mentioned that in 16th-century Europe, men would hold hands and embrace and share beds. It wasn’t just a sign of intimacy; that was the norm in that period. And I’ve just remained curious about that.

When I got into grad school, I still wanted to pursue that question, I still wanted to know about early modern forms of intimacy and relations that would look like homosexuality today, but instead were just norms of same-sex relations in a different era. That took me to Shakespeare because Shakespeare’s work is populated by lots of different kinds of loving pairs of friends and groups of friends.

Do you think your life philosophy has had an impact on your work?

This kind of work that I’m interested in analyzing through the Renaissance memory arts is really akin to what I’ve been talking about in terms of my own life and in terms of the Guggenheim Award. I’ve spent my entire life trying to make sense of the story of my life, and now I finally feel like the story of my life does make sense. I’m trying to understand that process – of how people create their own self narrative of their life – in my scholarship, because I’m finally accepting that, to some extent, I have control over the story that I tell myself.

The Guggenheim Fellowship

How did you feel when you received the first notification that you won the Guggenheim Fellowship?

It was really stunning, and genuinely didn’t feel real at first. The Guggenheim Fellows, since their inception, contain a 125 Nobel laureates, folks who have won the Pulitzer Prize, the Field medal, the Turing award.

What eventually I came to was that it was a real moment where I felt like I was being seen. When you apply for the Guggenheim, one of the main components is that you give them a life narrative. … There’s no word limit. So I told them the story of my life and what I’ve tried to do, and what’s really moved me. To win the award feels like another group of people looked at the story of my life, and it made sense to them.

The prize selection committee feels that I can be helpful to people in terms of the thinking I can do. And that was a really powerful retrospective announcement to me.

From what you’ve been telling me about your life narrative, do you think you’ve tried to answer the question of how to live a pleasurable life?

I’m only beginning to answer it now. For the first couple decades of my adult life, I always thought that the pleasurable moment was tied up with achieving a certain kind of fantasy about who I wanted to be. That drew me to living in a cool apartment in San Francisco with a friend of mine and going to work for a super interesting, historic California corporation – Levi’s. And whisking off to New York and seizing part of the internet boom, and trying to make it in Manhattan. And becoming a college professor and teaching Shakespeare to a whole room of students.

And what I realized was that when I was pursuing this pleasurable fantasy of who I might be, it was always from a distance. It was always on the horizon. And the further and faster I rushed to the horizon where I was certain it was, the horizon stayed the same distance from me. Now that I’m at Grinnell, and I live in a small town, and I spent a lot of my day walking with my dog around the same blocks, it’s a radical change for me.

Right now, I am choosing to just stand still. I’m really trying to figure out what’s pleasurable about this particular moment.

One Last Note

So what’s your haircare routine?

Well, for a long time, I thought the kind of haircut to have was to have the kind everybody else has. In college, my friend used to call it the “Friends” haircut. At some point, I realized the thing to do was not be like everybody else. The thing is to express yourself and to be yourself. That’s the whys and wherefores of it.

(long pause)

It’s a sustainable bamboo-based product.

Reusable, renewable, rejuvenating. Those are really the guiding words I use for choosing a hair care product.