By Marysia Ciupka

ciupkama@grinnell.edu

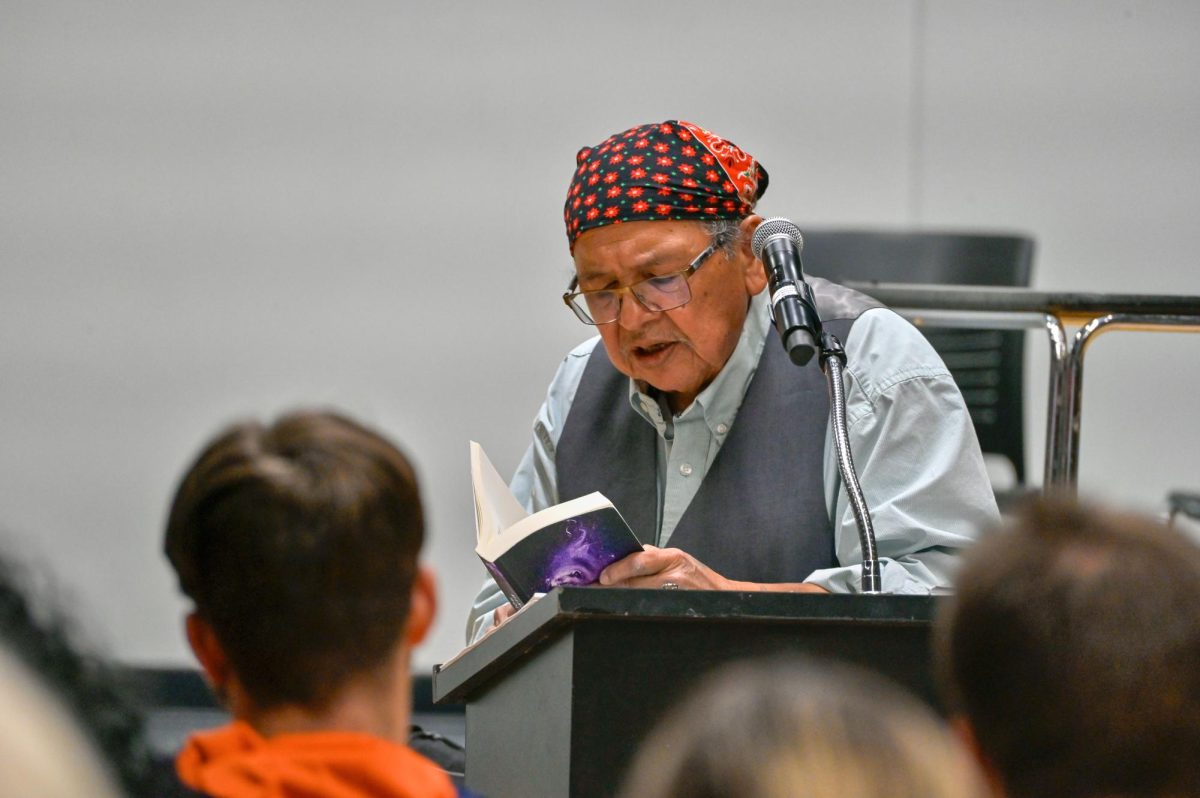

This week’s Scholars’ Convocation featured a talk given by Dr. Dominic Rubin, professor of philosophy and religious studies at Higher School of Economics in Moscow. Rubin spoke about the important role that Islam has come to play in Russia’s contemporary politics and culture.

He is also an instructor at Dickinson-in-Moscow program, as part of which Erhaan Ahmad ’18 took a class with him while studying abroad in Moscow three semesters ago. After coming back from his study abroad, Ahmad suggested to Professor Todd Armstrong, chair of the Russian department, that Grinnell should invite Rubin to give a talk about religion in Russia at the Scholars’ Convocation at Grinnell.

“I and Dr. Rubin established a close relationship,” Ahmad said. “As a researcher of Islam, I felt that he could understand an important part of my heritage and the place I was coming from really well.”

Rubin opened his lecture by stating that Islam in Russia is generally a question of “triple periphery.”

“Russia is on the periphery of Europe,” he said, “and Muslims in Russia are on the periphery of Russian society, while Muslims in Russia are peripheral to the Middle East. They are Muslim and Turkic speaking people but they don’t leave in Turkey or in the Middle East.”

At the same time, the issues that pertain to Islam in Russia remain relevant and worth learning about since it has become an significant element of Russia’s public life. Muslims in today’s Russia — both native and immigrants from Muslim Central Asia — make up 16 percent of its population.

Rubin suggested that mainstream debate on Islam in Russia usually comes down to two alternatives: either associating it with Ramzan Kadyrov, pro-Putin head of the Chechen Republic; or reducing the issue to discussion of Russian Muslims who have chosen to “opt out of the Russian story by going to Syria and becoming jihadis.”

Instead, Rubin decided to frame the issue through the following questions: what is Russian about Russian Islam? What is Islamic about Russian Islam? And, whether Russian Islam exists at all? While talking about the Russianness of Islam in Russia, an important distinction is made between what is considered russkii (русский) — ethnically Russian and connected to the historical and linguistic heritage of Rus’ — and rossiickii (российский) — an adjective pertaining to the state of Russia, which at the linguistic level allows for the inclusion of non-ethnically Russian groups into the broader notion of Russianness.

Another important factor that, according to Rubin, needs to be considered in tackling the issue of Islam in Russia is the political ideology of “the Eurasian” that emerged at the end of the 19th century. It is based on the idea that Russia is not Western, but that it is a “specific combination of Russian-Western elements.” As Rubin suggests, appealing to this ideology allows Russian Muslims to “keep in touch with their Islamic-Eastern roots” while still being situated “in the similar ideological space to the Slavic Russians.” Simultaneously, the spread of “Eurasianist” ideology ties well into the political interests of Vladimir Putin, who reciprocates by recognizing the importance of Islam in Russian public life and by supporting the political-religious hierarchy of “Orthodoxy first, Islam second.” The fact that the largest mosque in Europe was completed in 2015 in Moscow should therefore not seem incidental.

In this and many other ways, Rubin was trying to show that the discussion of Russian Islam can be executed outside of simplifying it into an issue of international security, but can be seen as a complex and developing movement with rich historical traditions — in the end, Islam came to Russia’s territory way before Christianity.

“I don’t think religion has lost its role in the world. I think that religion is very important and gives meaning,” Rubin said when asked about the importance of studying religion. “One should know about religion. … Religion can be instrumentalized, as we see it in Russia … so it’s important to know … what is true religion and what is false religion. … The difference between what political leaders are putting out there and how does it relate to the classical sources.”