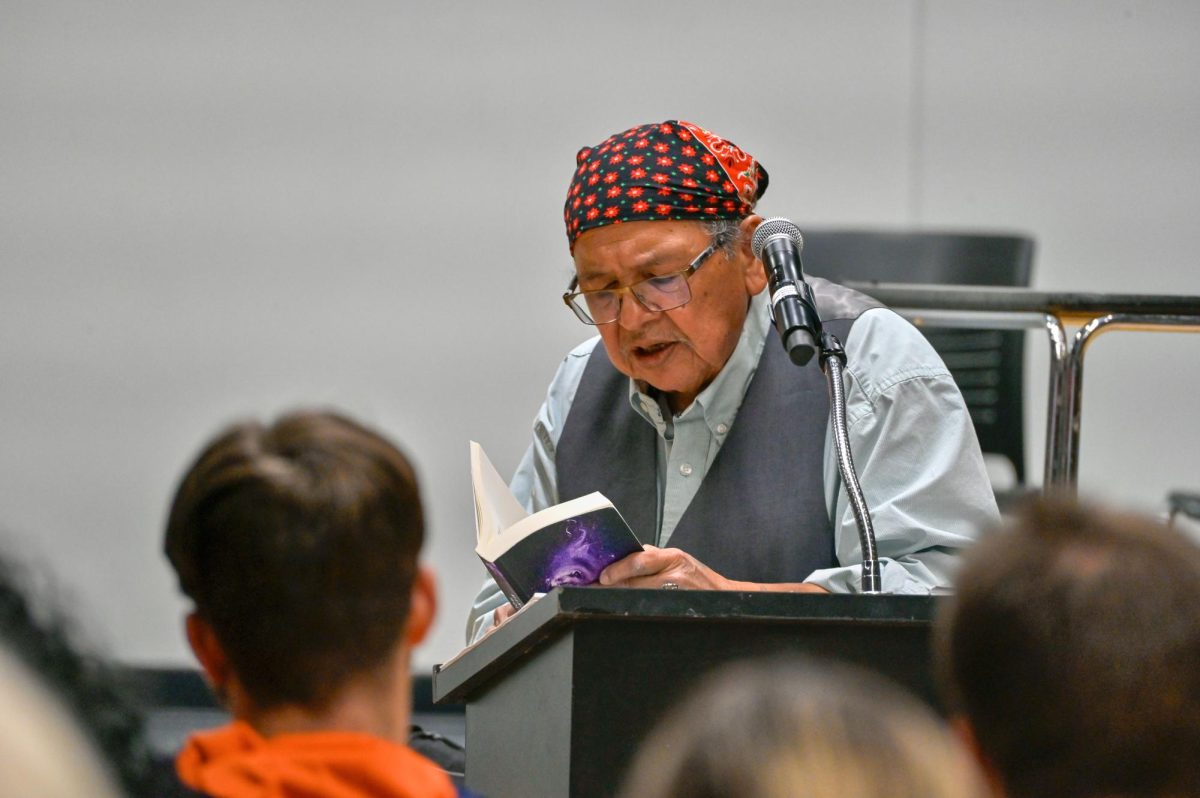

Natalie Rothman, associate professor of history at the University of Toronto, visited Grinnell last Monday night to share the story of a torrid love affair in early modern Istanbul. Rothman’s presentation analyzed a same-sex relationship between a dragoman, or Ottoman translator-diplomat, and Venetian barber in the sixteenth century Venetian embassy. By means of this microhistory, Rothman makes a case that the affair speaks to the role of domesticity and transimperialism in early modern diplomacy. The S&B’s Emma Friedlander sat down with Rothman to discuss her research, historical gender roles and the modern invention of East and West.

The S&B: What is significant about this particular case study in early modern Istanbul?

Natalie Rothman: The paper revolves around a case study or microhistory of a love affair between two young men working for the Venetian representative in Istanbul in 1588. It’s based on a transcript that I found of the Venetian representative — the bailo — interrogating 16 men who were current or previous resident employees of his house to testify about the nature of this love affair, what they had seen, what they knew. I was trying to use this case as a lens on broader questions about early modern diplomacy, about interactions between local Ottoman subjects and people coming from Venice all living and working together in the house, about different perceptions of sexuality and tensions around authority.

The S&B: You were trained as a historical anthropologist. What does that mean and how does it inform your approach to history?

NR: The program I was trained in was trying to give us grounding both in social theory and anthropological approaches and methodologies. … Most importantly, always thinking of questions of scale and the relationship between different units of analysis. … To give an example related to my research, not to assume that because the case is taking place in Istanbul then everything we need to know only takes place in Istanbul. People are always connected in all sorts of ways to broader processes and also broader temporalities. … We might identify as belonging to a certain religious community, to a certain gender, to a certain race, those kinds of things. What anthropology allows me to do as a historian is to always ask about the genealogies of these categories.

The S&B: You stressed in your talk that when studying transnational history, it’s important to understand context as a multidirectional process rather than as a binary. Why is this especially important when looking at the early modern Middle East?

NR: I think it’s especially important because you quickly realize that there is no such thing as the early modern Middle East. The Middle East is really an invention of modern imperial dynamics. What you have in the early modern period is an Ottoman empire that controls three-quarters of the Mediterranean and is very much integrated economically and culturally, I would argue, with its neighbors, whether it’s to the west, or what we now understand as the West or Europe and which is of course itself an invention of the precise same period, or in the East … Of course, that’s part of the legacy of imperialism, that we find it very difficult to imagine a world where there is no such thing as East versus West. These categories simply are not useful for studying periods prior to the 18th century. It doesn’t work in any sense.

The S&B: You’re not a historian of sexuality, but sexuality does of course play a significant role in this case study. What did the additional layer of sexuality and gender roles add to your greater study of transimperialism or diplomacy?

NR: I started this detective work of finding the women in records that were always ostensibly about men. I found this particular transcript that talked about this love affair and immediately began to wonder, given everything we know about diplomacy in this period and just how excluded women are from these spaces of diplomacy, how to think of homosociality, the gendered practices of living in segregated spaces, as something that is significant to this love affair. It’s not so much about causality or arguing that because there are no women, there is a love affair between men. I think that’s ridiculous. But it is about thinking of both the implications of the case and the kinds of understanding of the body and of the self in this homosocial space that might be relevant for how the protagonists understood themselves, how we can explain the fact that one of them is very strongly punished and sent to exile basically while the other one is sent home for a while and then brought back and goes on to have a wonderful long career in the service of the Venetians. Gender is very important there precisely because one of them is so plugged into this patronage network that is essentially about women, where women are very dominant in the political and economic underpinnings of Venetian diplomacy.

The S&B: Where’s your research headed from here?

NR: This is one of the opening chapters of a book I’m hoping to finish very soon, which gives the history of dragomans, these diplomatic interpreter-translators, working for the Venetians as well as for other embassies in early modern Istanbul.

The S&B: What draws you to the dragomans as a subject?

NR: I think they do play an important role in the genealogy of orientalism … but allow us to move away from a model of orientalism as something that hapless Europeans impose on the silent Middle East out of their own misunderstandings and misconceptions and malevolent will to power, and rather understands orientalism as something that emerges out of very intense interactions between political and intellectual elites from different places.