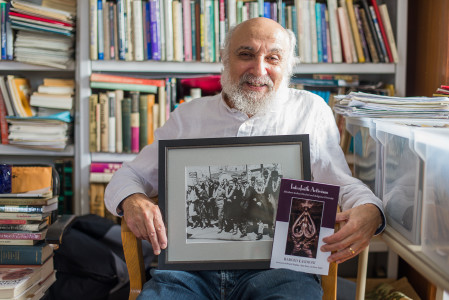

This week, The S&B’s Hunter Antonisse sat down with Professor Kasimow, Religious Studies, to talk about his new book “Interfaith Activism: Abraham Joshua Heschel and Religious Diversity” which explores the life of this influential Rabbi.

The S&B: I see that Alan Race, who you said was an outstanding expert in the interreligious field and the creator of the categories exclusivism, inclusivism and pluralism, is one of the people who wrote a foreword to your book Interfaith Activism: Abraham Joshua Heschel and Religious Diversity. Which of Alan Race’s categories do most people in the interfaith movement fall into?

Harold Kasimow: I would say that the interfaith movement consists mainly of people who are inclusivists and pluralists. Inclusivists believe there is truth and beauty in other religious traditions. We can learn a great deal from them but they believe their own tradition is superior to all others. Pluralists, on the other hand, believe that all traditions may be equally valid and that truth is not the exclusive possession of any one religious tradition. Most exclusivists are not committed to authentic interfaith dialogue because they believe that their own tradition is the only true one.

In my view, the most influential pluralist of the twentieth century was John Hick, a British philosopher and professor of theology at the University of Birmingham in England. He was interesting because he came from an Evangelical Christian background, but then became the face of the pluralist movement. Some of my heroes in the interfaith movement are Pope John Paul II, the Dalai Lama and Abraham Joshua Heschel who were deeply committed to dialogue among religions as a way to peace and friendship between members of the different religious traditions. Heschel consistently stresses that diversity of religions is the will of God. I see Heschel as a Jewish interreligious

artist who transcends the categories created by Alan Race.

Do you think that Heschel’s experiences during the Holocaust affected his views on the interfaith movement?

The Holocaust made a profound impact on his life. He once stated, “I am really a person who is in anguish, I can’t forget what I have been through. Auschwitz and Hiroshima never leave my mind. Nothing can be the same after that.” Heschel’s experience of the Holocaust is certainly one of the reasons for his social activism and his involvement in the interfaith movement. What people should know is that Heschel was the key advisor to Cardinal Bea, who was a decisive force in the drafting of “Nostra Aetate: Declaration on the Relation of the Church to Non-Christian Religions.” This extraordinary document is viewed by many as the most significant document of Vatican II and became a charter for interreligious dialogue. Although Heschel did not write much about the Holocaust, it was clearly very central in his life. From his experience of the Holocaust and his study of the prophets, he learned he had to become involved in the affairs of suffering human beings.

How did Heschel meet Martin Luther King, Jr. and other leaders of these movements?

Heschel and King were each invited to present at a conference in Chicago in 1963. The conference was called “Race: Challenge to Religion.” I find the affinity between their presentations very striking. They both quoted from the book of Amos: “Let justice roll down like waters, and righteousness like an ever flowing stream.” Heschel, the rabbi from Poland, and King, the Baptist minister, became very close friends. Dr. King spoke of Heschel as one of the persons who is relevant at all times. For Heschel, King truly represented the spirit of the Hebrew prophets. Heschel was the most prominent rabbi who participated in the well-known Civil Rights March in 1965 from Selma to Montgomery, Ala. After the march, Heschel stated, “I felt my legs were praying.”

How did Heschel feel about people that declined to participate in dialogue with other faiths?

Heschel believed that all human beings are created in the image of God. For him, that was a core idea of the Hebrew Bible. In one of his most important articles, “No Religion Is an Island,” he said we are all involved with one another because we are all inter-related. Heschel stated, “The choice is to live together or to perish together.” Clearly he felt that it is critical that people talk to each other and even more important that they listen to each other.

What is the main takeaway you hope readers get from the book?

I hope that people can open themselves to the possibility that there is truth and beauty in other traditions and that none of us has the ultimate truth. I believe that all religious traditions have valuable lessons to teach us about becoming better human beings. I hope people open their hearts to the idea that other religions can create compassionate human beings and that we can always learn something from a member of another religious faith. Sometimes members of another tradition can help us to fully appreciate the truths in our own tradition.