teresa fleming, News Editor

flemingt17@grinnell.edu

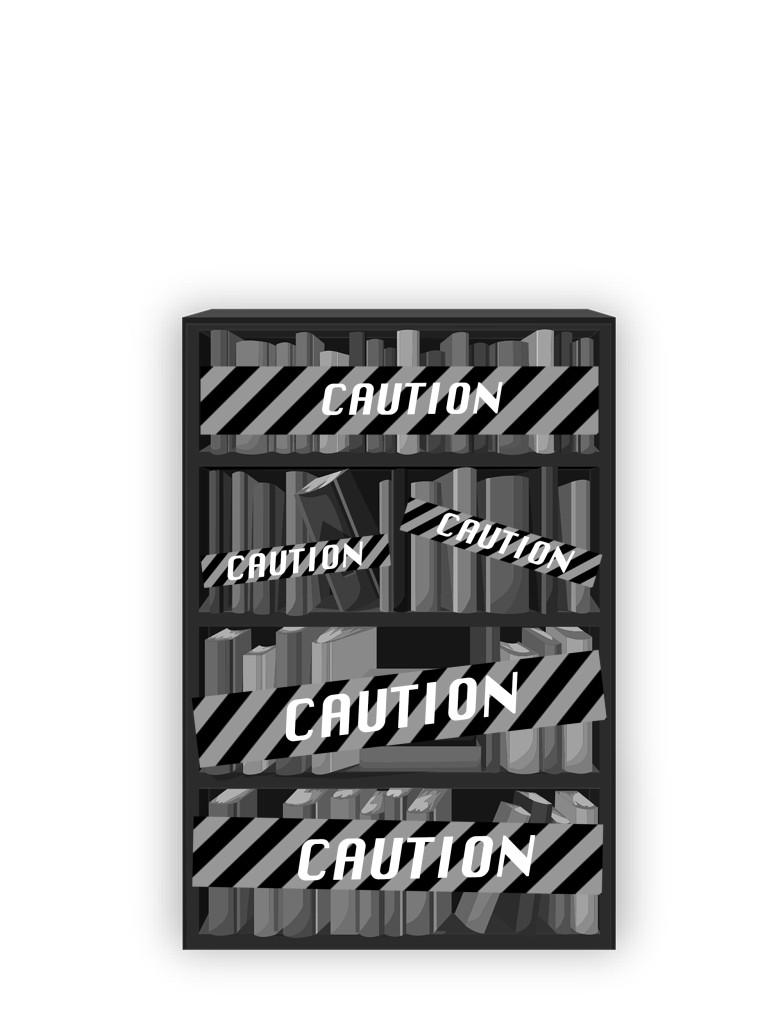

While trigger warnings have garnered national attention in recent months, students and faculty at Grinnell remain divided on how to handle triggering materials in the classroom.

Last spring, Professor Kelly Herold, Russian, was prompted to hold a class discussion of trigger warnings when she taught the novel “Lolita” to a General Literary Studies class. She found that most of the students in her class were in favor of professors giving advance notice if they thought material might be upsetting to students. But Herold also acknowledged that many faculty members also have concerns about issuing trigger warnings, which range from a reluctance to infantilize students to fears about facing repercussions for not offering sufficient warnings.

“How much are we held to it? What if we make a mistake? What if we didn’t even consider that this particular thing might be triggering and so did not mention it, did we do something wrong?” Herold questioned. “I think that’s where some of the concern comes from.”

Although the class expressed a preference for trigger warnings, Herold said she was encouraged by the discovery that none of her students refused to take part in subsequent class discussions of triggering materials.

“No one said, ‘Okay, this is in this text, I’m not going to come to the class discussion, or I’m not going to do the reading.’ Students who explained how they felt about trigger warnings said, ‘It’s good to know ahead of time so I’m prepared for it emotionally and mentally,’ which is a different thing from saying ‘I’m not going to read this book.’”

At Grinnell, as at many schools, the movement to include trigger warnings in the classroom has been driven by students. Toby Baratta ’17 is a member of Grinnell Advocates who has organized discussions with faculty about incorporating trigger warnings into the classroom. She sees trigger warnings as a way to make discussions more inclusive of students who have experienced traumatic events.

“If you’re looking at something from a sociological point of view, it’s easy to not think of it as a personal thing, but for students who have been through trauma, it’s not that easy and it’s not that simple,” Baratta said. “It’s a way of making sure that students feel safe in the classroom and that they feel okay expressing themselves.”

Professor Johanna Meehan, Philosophy, is not a proponent of trigger warnings. She sees the discussion of difficult topics as an important part of higher education and worries that a formally mandated system of trigger warnings could inhibit class discussions.

“I think the world is a difficult place, and one of the reasons we get educated is so that we come to know that,” Meehan said. “Much of what I teach … is about very painful, deeply political, deeply regrettable violence, and yet I feel like it’s our moral task to make sense of it.”

Meehan is also skeptical that professors can effectively predict what material might be triggering to a classroom of students. She suggested finding more personal ways to acknowledge course material that might be difficult for students.

“I have often told students that what we’re working on is difficult. It seems to me that that’s part of a human conversation, not something that should be mandated,” Meehan said. “I also think that it’s asking too little of human beings to not ask them to be sensitive to what’s going on in complicated situations. We all have our pasts and I think I expect all human beings to be at least honestly sensitive of that.”

Halley Freger ’17 also said she hopes that professors will pre-emptively notify students about potentially triggering materials in their courses, whether or not such notifications take the form of trigger warnings.

“I think a lot of people are critical of the language of trigger warnings,” Freger said. “I don’t think a trigger warning is coddling people. I think a trigger warning is trying to offer support and safety for people who need it.”

Freger recalled participating in a student performance which dealt with sexual assault. While there was no official trigger warning for the performance, audience members were warned ahead of time that the play dealt with upsetting topics. Freger sees such warnings as a way of facilitating conversations about difficult issues.

“No one wants to not talk about these things,” Freger said. “In fact, they want them to be talked about more, they just want to be engaged with [it] in an intelligent and safe way.”

Amidst campus-wide discussions of how to facilitate difficult conversations, Herold reflected that she herself has not yet elected to issue a formal trigger warning. Instead, she offered a “blanket trigger warning” at the start of her young adult literature class this semester, encouraging students to talk openly to her about their experiences with the course material.

“I just went in and said, ‘There’s something difficult in every single one of these books. Please come in and talk to me if there’s something that you don’t want to get into too deeply, for one reason or another.’”