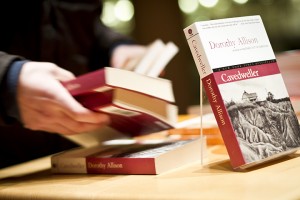

Dorothy Allison visited campus yesterday Thursday, Feb. 24 to lead a roundtable and read a short story as part of the Writers@Grinnell program. In addition to poetry, Allison has published novels, memoirs and short stories. “Cavedweller,” one of her novels, is the basis for the film “The Kids Are Alright.” Much of her work centers upon feminist and activist issues. The Scarlet & Black sat down with her before her reading to discuss the inspiration for her work and her writing process.

We are very excited to have you at Grinnell, where feminism and social activism are valued highly in coursework, student groups and generally across campus. Your roles as an activist and as a feminist have a significant presence in your writing. What is the relationship between these three components of your life—being a writer, a feminist and a social activist?

Well, oftentimes it is a reflection of biography and the accident of when you are born in history, for me very much so. It’s remarkable what happened in the United States post-second World War with the birth of the women’s movement and the gay and lesbians’ freedom movement, but also what happened in terms of education. I went to college on a full scholarship since I won a National Merit Scholarship, which is great but that meant I changed worlds instantly. My mother was a waitress and my stepfather was a truck driver. We were the working poor. I was the first in my family to graduate from high school. I was the only person who went to college. There have been six since but you have to understand that is six out of a family of hundreds. An enormous family, but the working poor. And what happened in the 1960s particularly was this huge bubble of people going to college who never would have gone to college before. People got an education, looked around, and realized that the world needed to be different. I became an anti-war activist when I was in college during the Vietnam war, in part because I was watching who went to war in Vietnam. And it tended to fall on the working poor and people of color, and that will radicalize you. And then there was the fact that during the late 1960s there was a huge small-press publishing boom, and there was a huge bubble in terms of the creation of a feminist press. The first magazine I worked with was “Amazing Grace” in Talahassee, FL, and it was a feminist magazine. All of these things came together, so there was no way to separate out being a writer, a feminist and an activist. It was all part of the same matrix at that moment in history. Now, that has changed over time and I have sustained all three, which not everyone does. And I took each of them very, very seriously because it was a way of saving my own life. The thing that falls out of talking about literature is that for some of us it literally makes the difference between death by despair and triumph, the vindication of your family your people. I use this phrase, my people, my tribe, but I belong to a range of tribes—the three you mentioned, and a lot more.

So is identity a highly important aspect of your writing? And not only your writing, but your role as an author?

It has been. But then again, I write fiction, which is the subversive part of it. But I tend to, in my fiction, assume identities that I care about deeply or am deeply curious about. Both “Bastard Out of Carolina” and “Cavedweller” are novels about violent families and the challenge, in both of those books, is that the father in Bastard has to make sense as a person. I had to imagine the reason why a man would rape a child; I had to figure out why that happens to make a character that I could make real on the page. That work shapes a lot of what I care about in fiction. In fiction, you figure out what might be sociological facts but then the characters have to rise to the level of poetry. They have to be almost biblical in their importance and in how they make sense. Everything has to connect. Fiction is not small. Fiction reflects the real world I see. It becomes a way of talking deeper about complicated subjects. For me, poetry is how you change people. Its how you get people to understand really difficult concepts. You go right for that emotional base and make connections and give them entre into a world that they haven’t seen closely. That’s what I try to do in literature. That’s important. That’s worth the trouble. Even if you never win a national book award or make any money, you will have made real what you see in your head and that is what’s important.

Have you developed a process for how to create that emotional depth within a character? Or is it just learned through time and experience?

Time and experience helps, but you need to read widely. You need to see how other people have done it and you need to see what you can stretch. Everyone comes to the work with their own gifts or with their own obsessions. Writing requires that you be somewhat deliberate about what you can do and what you can do well. I was raised in the south. I was raised in the Baptist church, and I was raised on really bad country music and rock and roll. And all those things come together with a particular approach to language that I can use and that defines a lot of what I do in my writing.I don’t want it to be trite or small or predictable. I want to do something deeper. People are very complicated, so I try to create characters that are also complicated. And then I try to tell you what they do in a language that sings.

Given the structures of oppression that are illustrated in your texts, would you consider your work to fall into the category of “political novel?”

For the most part political novels tend to be fairly simple. They seem to me that you could outline them. This happens, and that happens, and then we all rise up in revolution. No, no. It takes me a decade to write a novel. It takes everything I’ve got. It seems to me that if I’m going to do it, it’s got to do more than follow an outline and serve an ideology. I write big complicated books and I want there to be big complicated books out there, and that’s tricky.

Where do you draw the line between what constitutes fiction and what is classified as creative non-fiction?

I give a lot of room when people are writing memoir to reinvent conversations or accounts of events that are somewhat in dispute, in part because of my particular family. I write fiction by deliberate choice, because I can sharpen the contradiction; I can make characters that are larger than life and I want to do that. When I write essays, it’s almost painful for me to stay within the real. I worry sometimes that it is a genetic gift for lying, or maybe it’s just a southern affection, but I love a good story. Just like everyone in my family loves a good story. You always pick and choose what details you want to put in a story. Whether you are telling a true story or telling a fiction the writer crafts a narrative for a purpose.

Some of your text addresses very difficult issues, such as the sexual abuse that you mentioned. Are there any literary devices that you have developed over your career that allow you to describe potentially traumatic or disturbing issues in a way that is manageable both for you as the author and for the reader?

You have to work really hard. That is the bottom line. You have to find a voice that is believable, that can say terrible things in a matter-of-fact way. The other thing is even harder, and it is a kind of lyrical naturalism, and it’s mostly accomplished in dialogue. The reader needs to see all of the levels that the people having this conversation are not seeing. That’s just careful writing. You have to really know what you are doing, and you have to take some risks.

Have developments in your personal life, such as moving to California, becoming a parent, and reaching financial stability, affected your ability to write about certain topics?

Everything that happens to you affects your ability to write about certain topics. I was writing “Cavedweller” before my son was born, but I started the novel before Cissy, the daughter, was really angry at her mother. My son was born, I became a mom, and then I began writing Delia, because suddenly I was a mother and I discovered that all mothers are guilty, ashamed

and terrified. And so I made a guilty, ashamed and terrified mother. That was a huge shift because up until that point, I had always been the daughter in the narrator. It was the easiest to assume that persona, but then I started trying to step out of it and to write as the mother. And the writing of a novel takes so much time that a lot of different experiences can fold into it, and you assume different characters in the narrator. I have been all of those characters, parts of them are parts of me. It’s just that the glory of writing is that it exceeds you. It’s genuinely exciting and astonishing, and occasionally you go too far and have to cut a bunch of stuff out. I recommend it, it’s a way of understanding the world.

Do you have specific intentions for how different kinds of your writing will function?

I don’t really think about that in the process of writing. One begins a poem and the language catches fire. I find that you cannot control that. But I believe in the work, and the work is taking what anyone might call a shitty first draft and then making it better, and then better. But I don’t think about function. The function of all writing is to catch a reader. But there

is writing that satisfies the soul. Some things you write purely because they make you deeply satisfied. Sometimes I will make a person on the page that is so alive and so extraordinary.

In an interview in “Curve Magazine” in 2001 you commented, “I write who I can write— people I can understand. I can understand deeply wounded, hidden kinds of girls.” Are you conscious of your audience during your writing process and, if so, who do you imagine your audience to be?

It changes at different times. A lot of times I write for my two sisters, because of the shared world that we inhabited. So, that means I write for poor girls who feel hopeless, who feel wrong in the world. But I also very early on learned to write for other writers, and for a particular kind of writer. I write a lot for my friends who are dead, I write for Bo Housten and Alan Barnett. You wouldn’t know them, but they were young passionate gay writers who died too young. So I write for them; they are in my head. And you start writing for every character that you ever made up, it’s pretty peculiar. And you’re writing for yourself. And if you read wildly, that can get complicated.

Can you tell me more about The Independent Spirit Award that you founded?

I started it at the point where it suddenly looked to me like bookstores were endangered, and God knows I’ve been right. But the whole idea was to call attention to and honor people in small press. That meant people in small press publishing, book store people, some distributors, people that don’t generally get recognition, because writers, we get interviews, we get reviews, we get attention. But publishers don’t get any attention and my whole intention was to call attention to those people who are sustaining a cultural enterprise. The whole idea is that you are supposed to get rich in America, but that’s not most small press. Most people who work in the small presses and in bookstores do it because they love books, and they want the books to exist. I just wanted a way to call attention to what I think is a vital part of our culture that is enormously unvalued. And at this point we have lost more than half of the bookstores in the United States. Oy.

And now with the emergence of the Kindle and the iPad …

We are in a transitional phase, I’m pretty clear. I don’t object to any device in which people can get access to story, but I also love books, I fetishize books. We are remaking fulfillment in this country, and we are remaking the distribution of information. We have to see what will come and we don’t know, and this is the thing that I think is brilliant that historians can do and I cant, they can say “I don’t know” and be calm about it. We don’t know what will happen with books. But, meanwhile, there is this huge boom with small press publishing that is happening, a rebirth with publishing online and whole new venues for publishing memoir and essay and story. I expect to sell short stories on iTunes, both audio and digital versions. I think we don’t know yet what the future of books will look like. It could be exciting, but then again it could be the Black Death. Just for a while, until we get to the renaissance.

Brenda McClain • Feb 25, 2011 at 9:19 am

Dorothy Allison is, without a doubt, one of the most gifted writers we have today. I love, especially, her words about writing large people, not keeping them small. “In fiction, you figure out what might be sociological facts but then the characters have to rise to the level of poetry. They have to be almost biblical in their importance and in how they make sense. Everything has to connect. Fiction is not small.” Thanks, Dorothy, for your wisdom.