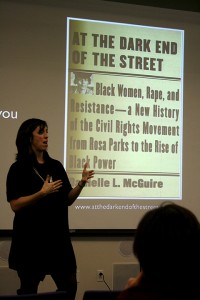

As part of Black History Month, the College brought Danielle McGuire, author of “At the Dark End of the Street:Black Women, Rape and Resistance—A New History of the Civil Rights Movement from Rosa Parks to the Rise of Black Power,” to discuss sexuality and civil rights.

How’d you get interested in this sort of work?

I decided I wanted to focus on history when I was an undergrad student, my junior year. I was taking a civil rights history class and we were focusing on Mississippi. We were so interested in these books and we had this great professor so we asked him to take us to Mississippi and he said okay. So for Spring Break, our class went down to Mississippi. When we were there we did interviews with movement veterans, we learned how to use the archives and dig up documents and we got to talk to the people who made the movement. It was new. It was real in a way that wasn’t in the books.

But [my moment] sort of happened when we saw this highway sign for Duckhill, Mississippi. We had read about Duckhill–there was heinous racial violence in Duckhill in the 1940s. Two men were tortured with a blowtorch, the eyes were removed with corkscrews and then they were set on fire. Just for violating for Jim Crow, some racial order. And you read about it, and you read and you read, but then you close the book and it’s done. You don’t think about it being real people and real places, something that’s still there. So we’re driving down the highway and we see the sign for Duckhill. And everyone got silent. It was the first time I was really struck by how history isn’t something that is far away, but it’s something that is really close, and is something that’s still with us.

Faulkner said once that, “The past isn’t dead and buried. In fact, it isn’t even past.” And it’s so true. We tend to think of things in book as not being real, or once they’re in a book, they’re so far away … but these are people who are still with us. So, that’s the moment in that trip. The process of making history, discovering history and putting the stories together to tell a narrative, that’s when I thought, this would be a cool job. I’ve always been interested in the civil rights movement, but it was during grad school that I stumbled across this story about Betty Jean Owens in 1959 and decided to focus on that. But I put it aside for a while, because I thought it was a one-time case. But over the next few years, I kept discovering these stories again and again and again, and I thought, ‘There’s something here, there’s a bigger story to be told that hasn’t been told yet.’

There has been some controversy over your depiction of famous black women involved in the movement. Specifically, how does your depiction of Rosa Parks compare to the standard presentation of Rosa Parks and her symbolic representation of racial equality, as opposed to racial and gender equality, etc.?

I think it’s really important to recognize the fullness of Rosa Parks and that we do not try to paint her into this symbolic, simple woman whose spontaneous decision to defy Jim Crow launched this movement and then the walls of segregation came tumbling down. It’s mythical and it’s a great story, but it’s useless history. It’s useless history. The more we think of Rosa Parks as being burdened by tired feet, and one day just deciding to throw in the towel and boycott, the further away we get from learning how change happens and learning how to make change ourselves.

If we know more about the real Rosa Parks, Rosa Parks the militant activist, Rosa Parks the detective for the NAACP, Rosa Parks the anti-rape activist before the women’s movement, Rosa Parks the Black Power advocate after the bus boycott, Rosa Parks the follower of Malcolm X. That Rosa Parks? That Rosa Parks was fierce. She’s so much more interesting. And it teaches us that you make change over time, over a lifetime. And what you’re focused on will change as the times change. So we should scrap the old Rosa Parks and use the fierce Rosa Parks, because not only is the story so much more interesting, but it’s also useful history.

Do you have any personal connections to the civil rights movement of the 60s?

No, not really. All I can say is that I’m a child of Black Power, which is a funny thing to say for a white woman. But the truth is that the Afro-American Studies Department at the University of Wisconsin is a direct result of the black power movement. For every university, it’s true. Without the Black Power movement, I wouldn’t have had a department to go into. I don’t think when African-American students of the 60s sat in on college campuses demanding a department for themselves they expected white students to become majors and take on this profession, but that’s what happened. And it’s a good thing that we all have access to this history now that people didn’t before the Black Power Movement.

How has being white affected or influenced your research?

I have white-skin privilege. I know that it benefits me in certain ways and in most places. I’m cognizant of that. I try to be really responsible about the ways in which I can use this privilege and the ways in which I can help try to destroy it. I haven’t encountered any difficulty speaking to anyone—white or black—about the book or getting access to interviews or information. I think that’s a testament to the Movement and to the fact that African-Americans fought for the whole world to be a better place, not just for them but for everybody. They called on America to be as democratic as it promises to be. They asked America to live up to its promise. It wasn’t just a movement by blacks for blacks, it was a movement by African-Americans for everyone and for America. It’s kind of a hard question to answer; my skin may have gotten me on a train some places that I wouldn’t have if I was black, and it may have denied me entrance to some places because I’m not black. Some of those things I have no way of knowing.

Do you have any future ideas? Are you interested in contemporary research of black women and sexualized violence?

I’m still a historian. I still like history. I like watching history unfold, day-to-day on the news. We’re living in a really historic moment; we’re watching this world shifting movement. There’s a lot going on here. But I’m a historian, so we need distance to analyze it with objective eyes. So, I’m still interested in the Movement, I’m still interested in the way that African-Americans and women pushed for democratic rights, what Hasan Jeffries called “freedom rights.” But I’m not sure where that will take me yet. I don’t have any concrete ideas for future work, though at lunch we were talking about writing a book about Mike Tyson. Who knows?

Why black women over women in general?

I’m sure there are white women of sexual violence, but I was focused on this legacy that was rooted in slavery of white men attacking black women with impunity and believing they had the right, they had access to black women’s bodies without their permission, without their consent. and most of the time, they got away with it. That’s a legacy that is rooted in slavery and is unique in many ways to the Deep South, because of slavery. I’m not saying it didn’t happen in the North, I’m just saying that the ways in which it happened—almost ritualistic fashion—across the South is unique to that area because of the institution of slavery. Also, my focus was on black women because we spend a lot of time talking about white women and their position atop a racial hierarchy. White women were painted as these pure victims, pure women, whose defense justified lynching and other kinds of racial crimes. So I felt like black women’s stories were consistently pushed aside, whether in favor of talking about black men or white women. Black women’s experiences really hadn’t been grappled with. I really wanted to know what were they dealing with on a daily basis? Where they testifying about? What were their concerns? What personal things were they concerned about? Were they treated like human beings, and if not, how not? That was my focus.

What do you hope students get out of your work?

I hope a couple things. I hope it helps students see that the movement was bigger than Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks and the iconic people we associate with the movement. It had to do with everyday struggles that people faced, and that black women paved a way for all women by speaking out decades before the women’s movement, by using their voices as weapons of protest and their testimonies as weapons of war. I hope it teaches women and men that are victims of crime and oppression to use their voices to testify against these crimes because it’s our testimonies; it’s our voices that often bring an end to these things. If there’s something that we feel is unjust, we should speak out about it. If they had the courage to do it, in the dark days of Jim Crow, when their lives were at risk for doing so, then we should have the courage to do it today.