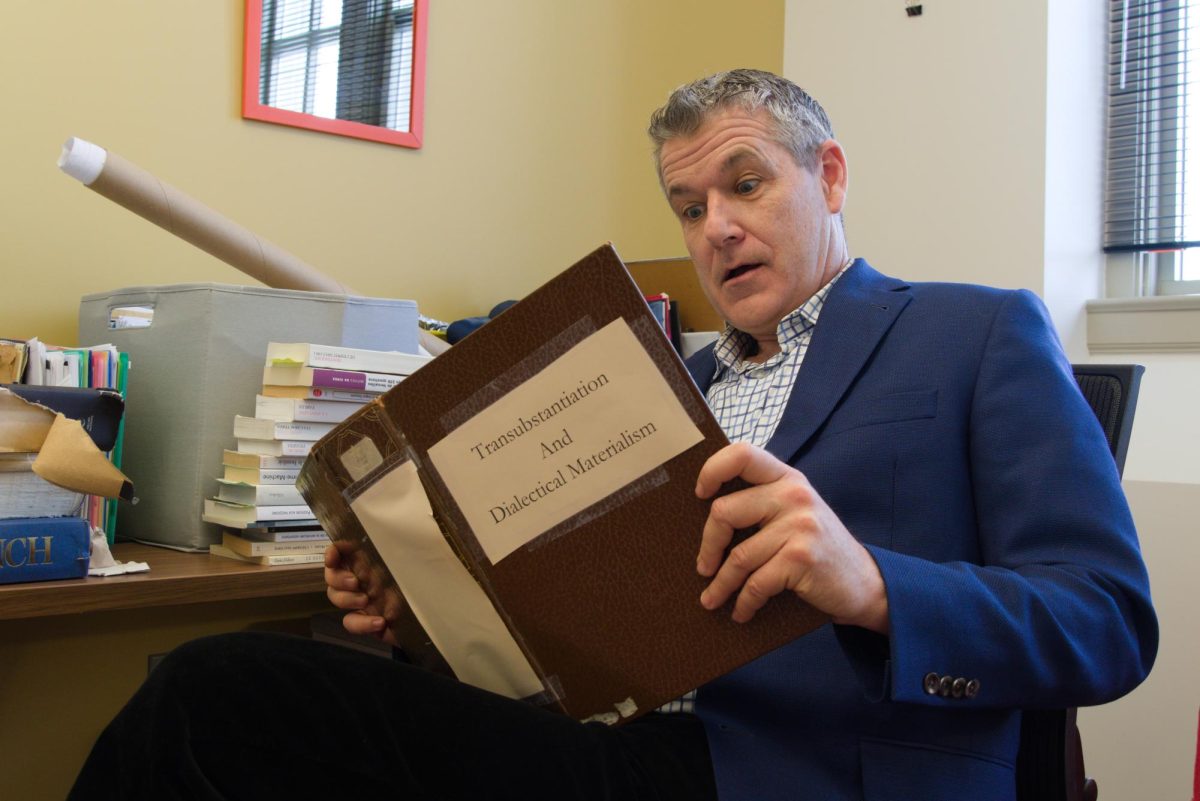

For years, Iowa was considered a swing state, one that could go in either direction for America’s popular political parties. That is no longer the case, said Tom Beaumont, political reporter for the Associated Press. At a talk hosted by The Scarlet & Black on April 9, Beaumont reflected on his extensive career in political journalism and years of reporting on the Iowa Caucuses.

“I report on politics a thousand miles away from the scuttlebutt of Washington,” Beaumont said. “The best way to find out what’s going on in America is to look right here in the middle of the country.”

Beaumont first talked about Iowa’s extensive history as a swing state, describing the 2000s as the period during which “political balance was at its peak in Iowa.” He used the 2004 presidential election between George W. Bush and John Kerry as a prime example. “That year, Bush campaigned in Iowa ten times and ultimately won the state by a thin margin of just around 10,000 votes,” he said.

However, during the 2010s, particularly after Donald Trump’s 2016 landslide victory in Iowa, the state no longer followed this competitive dynamic. Referring to the 38 counties that voted Democratic in 2012, Beaumont pointed out that all but seven counties flipped Republican just four years later. “Those same 31 were carried away by the very man who spent years undermining the constitutional eligibility of the first Black president,” Beaumont said of Trump. Poweshiek County was part of this sweeping transition, which, according to Beaumont, did not occur with such magnitude in any other state.

“Poweshiek County is at the fault line of what has been happening politically in this country for the past 20 years,” Beaumont said.

Regarding the consequences of Iowa’s lost political balance, once sustained by the constant competition between two parties, Beaumont pointed to the bill that removed gender identity from the Iowa Civil Rights Act earlier this year.

One reason for Iowa and the broader Midwest’s shift from swing states to Republican strongholds is the erosion of Democratic support among working-class voters, a consequence of shutting down local industries, Beaumont said. He added that there were once Democratic-leaning counties along the Ohio River, where towns boasted diverse industries and well-paid union workers.

Beaumont attributes the closing of factories providing thousands of jobs to dramatically changing the political climate. Beaumont said working-class Democrats vanished as a force in the Midwest and along the Ohio River as a consequence.

“Working-class counties that were once the home of manufacturing jobs are now Trump country. It’s a fact,” Beaumont said.

Another reason Beaumont attributes to Iowa and other Midwestern states shifting from swing states to embracing Trump’s politics is the growing distrust Americans have in non-partisan media. While he acknowledged that this is not a new phenomenon in American history, as most newspapers in the 19th-century were partisan, Beaumont said the importance of understanding why this shift back to a past trend is happening now.

“I want to know why faith in hard-working, fact-based, non-partisan news is losing credibility,” Beaumont said.

The Pew Research Center found that in the 1990s, 60 million households subscribed to a daily newspaper, while in 2020 that number had dropped to only about 20 million.

Beaumont said it is important that media outlets are granted access to government information in order to provide accurate and critical evaluations on policy, especially in light of the Trump administration’s constant attacks on the media.

“Governments also make mistakes,” Beaumont said.

In February, the Trump administration barred the Associated Press from the White House press pool. This ban was lifted by a federal judge on April 8, the day before Beaumont’s visit to Grinnell.

“The mainstream media is under attack like it’s never been before, and it’s starting to take hold,” Beaumont added.