It’s a sunny, blustery Saturday, and a group of Iowa farmers are arguing about pesticides in a barn. But all is not as it seems. The barn is actually serving as a theater, and the farmers are actors. They’re surrounded by an audience of 35 occupying neat rows of folding chairs and low wooden benches. The stage is bordered by bales of hay and barn doors that rattle with each gust of wind. A gray cat wanders through the rooms, occasionally padding onstage.

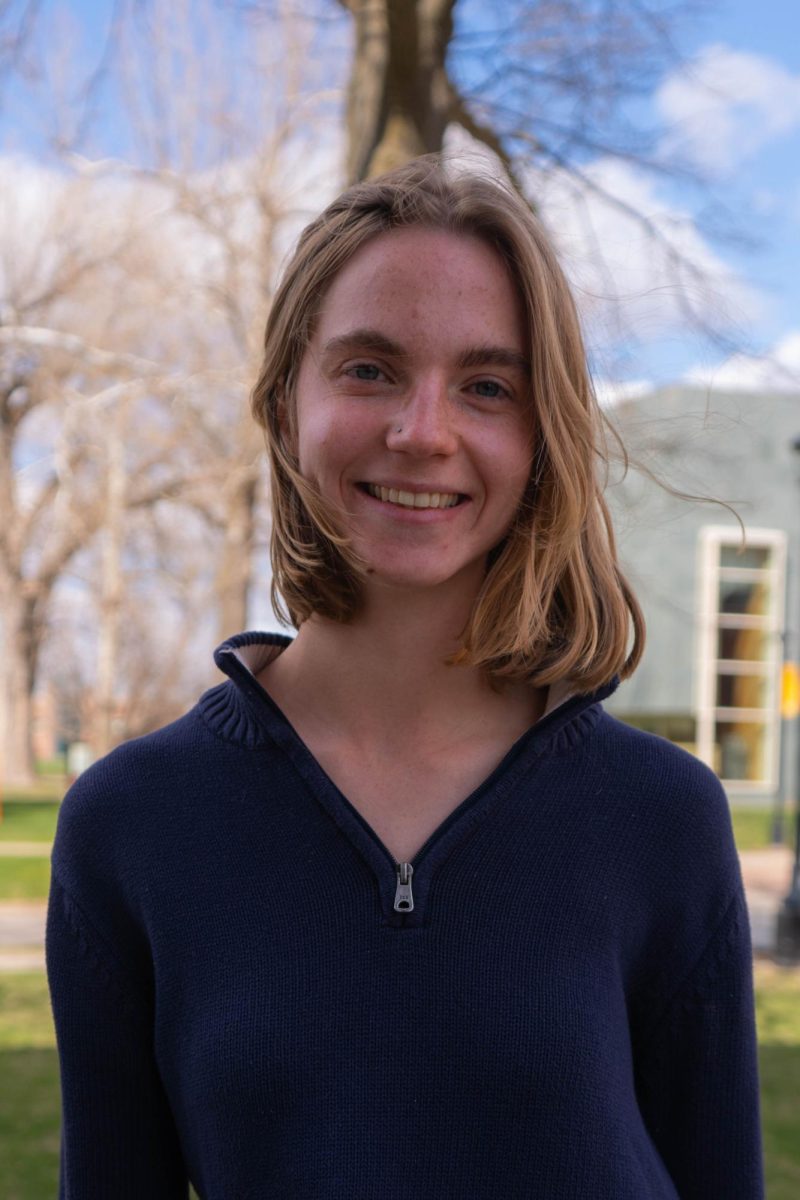

This is the fourth stop on the spring tour of Iowa playwright Taylor Sklenar’s “Resistance,” produced by the EcoTheatreLab (ECL). ECL is an Ames-based artists’ collective that works on projects surrounding sustainability and climate action. The group’s main team consists of Sklenar, Charissa Menefee and Vivian Cook.

Both Menefee and Cook are involved in the spring “Resistance” tour –– Menefee plays Janet Foster, a farmer’s wife and dialysis clinic employee, and Cook serves as the play’s tour and stage manager. Menefee was unable to attend the Grinnell performance due to injury, so Cook stepped into the role of Janet.

“Resistance” came to Grinnell on March 29 and was staged in the barn at Grin Cupola, a contemporary art space located on a century-old family farm at the outskirts of Grinnell.

The play follows six farmers over the course of several years as they reckon with a fictional herbicide called “ThunderFlex.” Set solely in a church basement in a small, unspecified Iowa farming town, the central theme of “Resistance” is the debate around the use of “TF” and its consequences.

Though the church basement setting remains the same through the entire play, its function frequently shifts. The play’s characters congregate in the basement for Halloween celebrations, Easter potlucks, Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, crafting circles, pizza nights and goodbye parties. Small prop changes between scenes denote each of these events, and their recurrence helps mark the passage of each year.

“All along as I was writing it, I was trying to think about, ‘What are the audiences that I want to engage this story with?’ And that was a big reason why all of the scenes are set in a church basement,” Sklenar said. “That’s a space that basically every small town has, and I was very much envisioning the small town church basement that I grew up going to all the time.”

The central conflict in “Resistance” occurs between Frank, a commodity farmer who is the first to begin using TF, and Sydney, a younger, college-educated organic farmer and the sole holdout against the herbicide.

While writing “Resistance,” Sklenar wanted to explore the issue of pesticide use beyond straightforward condemnation. “I think that this is more complicated than that, and I try to take an even hand with this play in terms of the different kinds of farmers and perspectives that inform what goes into our communities,” he said.

Frank, the play’s most ardent supporter of ThunderFlex, helps reflect the complexity of conversations surrounding pesticide use.

“I think Frank is tragic. He’s made the right moves every step of the way and sees himself as a land steward,” Sklenar said. “It’s a matter of making sure that the characters, the way that they live, provide entry points that reflect lots of different experiences.”

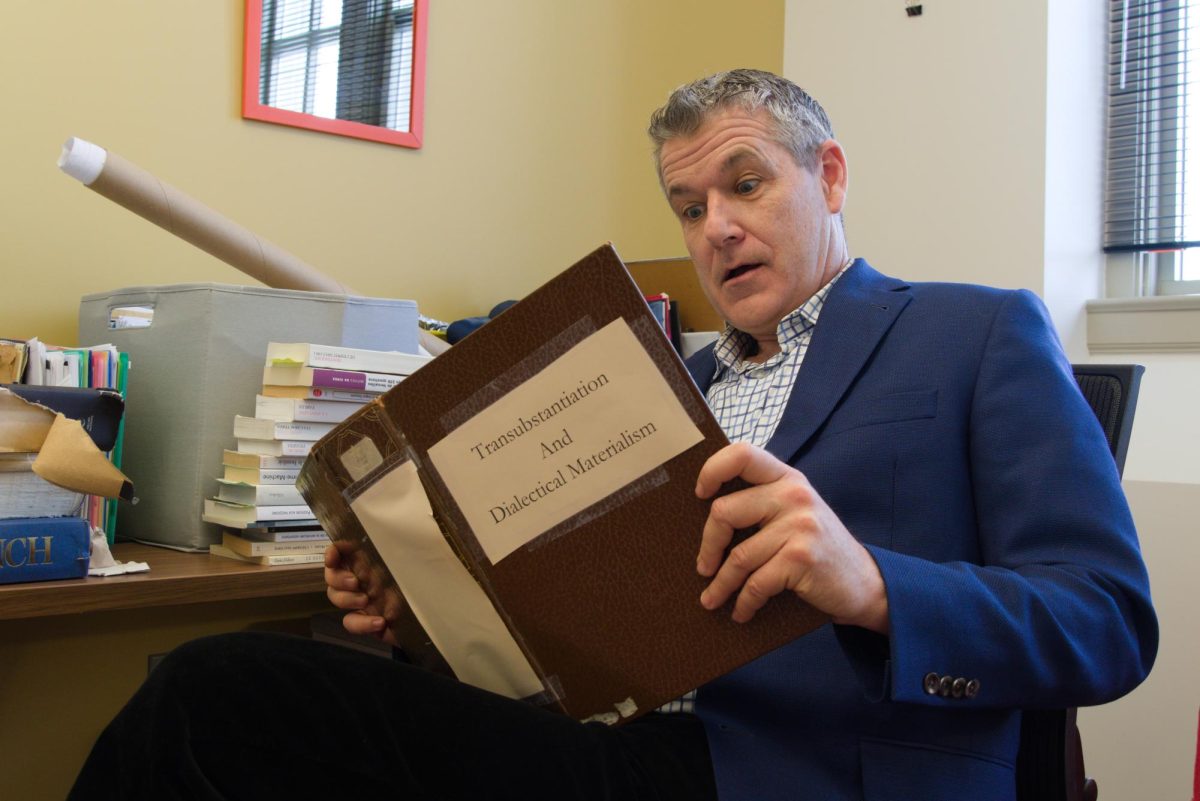

K.L. Cook, who portrays Frank, said his character is “maybe the antagonist, but hopefully he comes across as sympathetic on some levels.”

Cook is the co-director of the Master of Fine Arts Program in Creative Writing & Environment at Iowa State University, where Sklenar received his MFA along with a Master of Science in Sustainable Agriculture. Sklenar began writing “Resistance” while at Iowa State, where Cook first encountered the play as part of Sklenar’s thesis project. From its conception, “Resistance” was envisioned as a production that would tour Iowa.

“I knew early on in the process that I was going to want to take this to farming communities down the road at some point, but that was something I tried to write into the script as well,” Sklenar said.

Beyond barns, “Resistance” has been staged in a variety of nontraditional theater spaces over the course of its five-stop tour in Western and Central Iowa.

“The goal was really to create a story for farmers,” Sklenar said. “And that’s part of why we’re doing it in these nontraditional spaces. We’re not doing it in theaters. We’re doing it in nature centers and church basements and memorial buildings and barns, libraries, because those are spaces that I think are more welcoming and that people are less afraid to step into, especially if you don’t see yourself as a ‘theatre person.’”

“We’re taking stories and art to communities that say … ‘We’ve never had a play come here.’ So there’s something really energizing about that,” he added.

Joe Tuggle Lacina, the director of Grin Cupola, helped the ECL bring the play to Grinnell. The Grinnell Area Arts Council and the College both served as funding partners in supporting the tour’s Grinnell stop. All three funding partners have their own performance spaces, but Sklenar and the ECL wanted to stage “Resistance” in the barn.

“I offered several spaces,” Lacina said. “They could collaborate with the Arts Council or do it in the Cupola, or do it on other spaces on the farm, but I think this seemed like the grandest and maybe the most pointed or subversive, just because it’s on a farm, a conventional agriculture farm, it puts you –– if you’re not in the issue already –– in the midst of it.”

Sklenar, who described his work as located at the intersection of science, communication, storytelling and agricultural rural life, saw herbicide resistance as an issue of growing importance in Iowa –– and an issue that is difficult to engage with for many farmers.

“These are challenging conversations to have,” he said. “I think story, and especially theatre, where you’re literally sitting in a room, looking across the stage at other people, that’s a really valuable tool.”

To encourage further dialogue, each performance of the play has been followed by a community conversation in which Sklenar and the play’s actors facilitate large and small group discussions around the themes of “Resistance.”

“I like to think of theatre as a tool for opening up dialogue, and that’s kind of the goal,” Sklenar said.

The play’s Grinnell performance occurred just days after the Iowa Senate passed a bill that would shield the manufacturers of pesticides from “failure to warn” lawsuits. Though the bill itself did not inform the writing of “Resistance,” the play’s content is closely related to the legislation. “Resistance” concludes with the discussion of characters pursuing a lawsuit against the manufacturers of ThunderFlex, something that Senate File 394 seeks to prevent.

“It feels a little eerie to have this happening right now, just as we’re doing the performance,” Cook said.

In the community conversation, audience members quickly connected the play to the legislation.

“This play felt incredibly timely because of the bill that went through the Iowa legislature this week that is seeking to ban lawsuits against herbicide and pesticide companies for the health effects we’re experiencing as Iowans,” said Noël VanDenBosch, the play’s costume designer.

Though VanDenBosch worked on costuming for the production, this was the first time she had seen “Resistance” live onstage.

“Having it here, on a farm, was a really awesome avenue toward conversations that I think we wouldn’t have had otherwise,” she said. “Having legislators consistently choosing to bring up and write bills and legislation that actively harm Iowans is devastating. So being here felt like these are important conversations to be having, and hopefully the touring that they’ve done to different rural communities is helping people start to have those conversations.”

As part of the community dialogue, Sklenar asked for one-word reflections on the play. Audience members began to call out. “Realistic,” one said. “Anguish” and “anxiety” soon followed. “Community.” “Empathy.” “Compassion.”

The final stop on the spring tour of “Resistance” was on April 5 at the Ames Public Library.