Poweshiek Community Action to Restore Environmental Stewardship (Poweshiek CARES), an organization dedicated to promoting sustainable agriculture and awareness of food system issues, platformed sustainable farm reformation at their Annual Meeting on March 26. Guest speaker Tanner Faaborg, an Iowa native, spoke to an audience of roughly 90 community members, college students and faculty at Drake Community Library about how he transformed his traditional family-owned farm into a thriving mushroom production business, emphasizing the importance of sustainability in an industry increasingly dominated by large-scale commercial farming.

Since 1990, the number of factory farms — also known as Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) — in Iowa has increased five-fold, which placed the state seventh in the nation for cattle production and contributed $9.45 billion to the Iowa economy in 2023. Yet, this expansion has led to significant environmental pollution, such as water contamination from excess manure runoff and air pollution from methane emissions.

In 2019, Iowa was the nation’s top animal waste producer, its swine and livestock population producing 68 billion pounds of waste annually. Further studies have found that in private wells, nitrate contamination from manure has nearly doubled between 2002 and 2017, reaching levels associated with increased risk of cancers and birth defects — contamination that will cost Iowa residents $333 million in nitrogen removal systems in coming years.

For families like Faaborg’s, there is also the deeply personal loss that comes with commercialization of local agriculture. In his talk, Faaborg described his childhood in the fields, raising cows, collecting freshly laid eggs, driving tractors and making applesauce from the trees his family grew. Yet, concerns over finances and supporting five children pushed his parents to contract their hog farm and labor out to a farm corporation, expanding what was once a small, 25-acre family establishment into a facility for intensive hog farming.

“The lack of autonomy with contract farming is one of the worst parts about it,” Faaborg said. It took his family nearly two decades to pay off construction loans from the farm corporation. “My parents really didn’t know, but once you’re a contract farmer like this, and you make this investment, you’re on this treadmill that is really hard to get out of.”

Although Faaborg worked hard through his childhood, he said, “It was a good life… we felt like everything had a purpose.”

This shift towards consolidation and contract farming was widespread in the rural area where Faaborg lived, as more families left and the community shrank. Shortly after Faaborg graduated high school, it closed permanently due to dwindling enrollment.

(Marc Duebener)

Eventually, said Faaborg, “My parents didn’t want to do it anymore.” Faaborg’s parents had been earning more 20 years prior, when they still owned their farm. They talked about selling it. Hearing that, Faaborg said, “All the kids went crazy.”

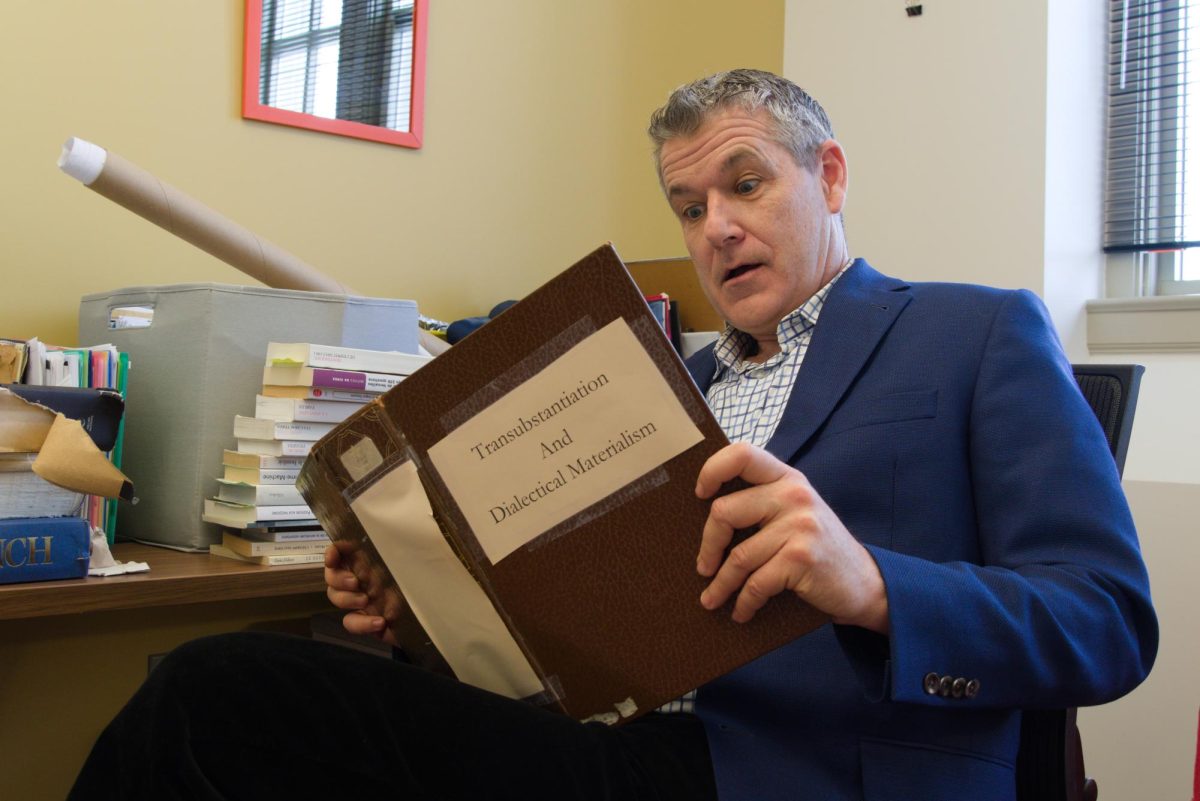

It was at the University of Iowa that, as an undergrad, Faaborg discovered a passion for sustainability and reformative farming. He soon discovered what would become his big break — mushrooms.

“I said, ‘Well, what if we repurpose the barns and we do something else?’” Faaborg said. “I didn’t know anything about mushrooms before getting into this, but I went down this mushroom rabbit hole that I am still in. It’s so fascinating, just the versatility of it, the medicinal benefits, the fact that you can have fresh produce.”

Faaborg was met with initial skepticism from his family, which he called his “first challenge.”

“My family thought I was crazy,” he said. “In traditional family farm culture, there’s a certain pride in working hard and providing for your family … There will be people saying not just, ‘Is this unrealistic?’ but they’re going to be partially hurt by it. I didn’t want to demonize them, I didn’t want them to feel guilty.”

Faaborg said he “forged on” regardless. He received financial support from the nonprofit organization Transfarmation, which he said “helps farmers transition away from CAFOs to more sustainable, plant-focused business models.” His gamble on the versatility of the mushroom gave rise to 1100 Farm, a modern, solar-powered mushroom production facility that has since been featured in The New York Times.

According to their website, the family-run 1100 Farm is “cultivated in the heartland with people and planet in mind,” and is “creating the future of agriculture with integrity and innovation.” Products available for purchase on their online shop include lion’s mane dark hot chocolate and reishi mushroom tincture.

“Some of our goals are the diversification of the ag sector, instead of just row crops and CAFOs,” said Faaborg. “Let’s localize the food economy. I mean, it’s ridiculous that we’re importing all this food … when we can grow it right here.”

Val Vetter, 76, president of Poweshiek CARES, said that what Faaborg is doing is “unbelievable.”

“All these family farms are taken over by corporations who contract people like Tanner’s family, and these people make practically nothing,” she said. “It’s a really, really bad thing for Iowa, the disintegration of communities … What Tanner is doing counteracts that.”

Faaborg said he is currently continuing his study on the medicinal benefits of mushrooms, but that their “main goal right now is to finish the reformation of hog farming.”

“Just providing that model and being that catalyst for change can really have a positive impact,” he said. “I think policymakers want an example. They want to see success before they are willing to maybe make some policy changes. And I think the same is true for other farmers … I think we need to be the success for others.”