Let’s say the government decides that some subject at Grinnell College — history, gender studies or transubstantiation — is so sinister that it can no longer be taught and all its practitioners must be fired.

“Since the teaching of transubstantiation has potentially serious adverse foreign policy consequences for the United States, the U.S. Secretary of State has determined that any federally-funded college or university must immediately cease all classes in transubstantiation under penalty of prosecution.” (Executive Order No. 2578305)

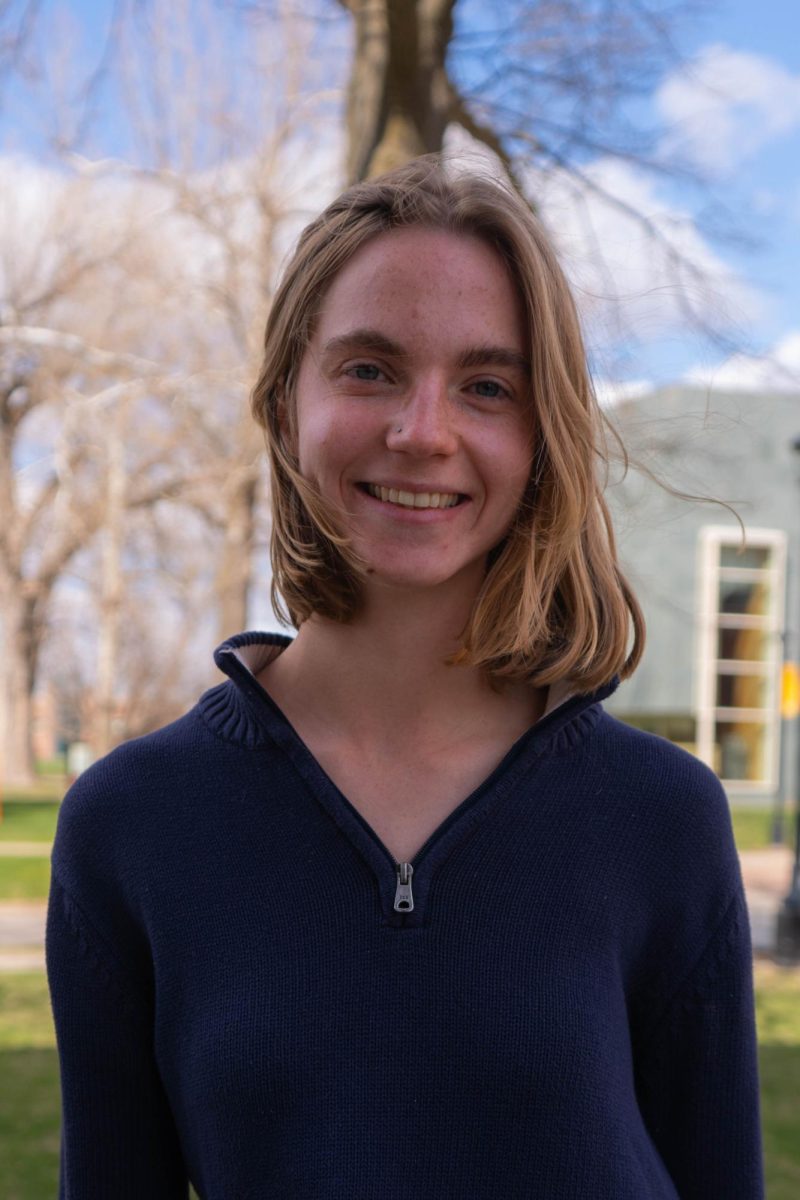

Dr. Wei-Chen O’Leary, Grinnell College professor of transubstantiation, is summoned by Throgmorton Snodgrass, Grinnell’s vice president for academic affairs.

“Well, O’Leary, the Board of Trustees would like you to resign to prevent further damage to the College’s reputation, and to comply with the law,” Snodgrass intones. “But don’t worry: we’ve put together a generous severance package for you.”

Snodgrass is an earnest, well-meaning type, and he very compassionately lays out the plan for the termination of O’Leary’s career. In response, O’Leary very compassionately tells Snodgrass to shove it, and she hires a lawyer.

Assuming the judicial system is still functional, the case makes its way to the U.S. Supreme Court, where the main question is as follows: can the state punish an institution for teaching a subject it deems dangerous?

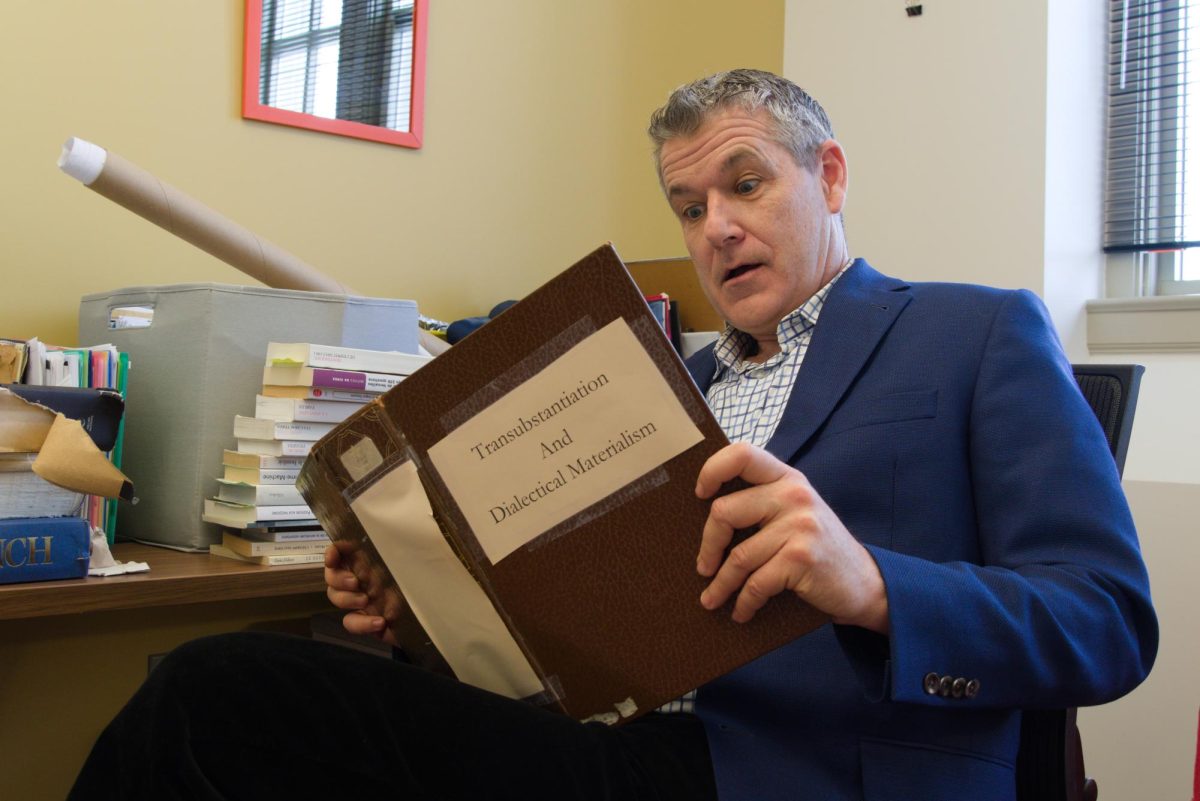

The good news — if such a term is possible here — is that the U.S. Supreme Court already decided such a case nearly seventy years ago, at the height of the Red Scare. The state of New Hampshire had authorized its attorney general to prosecute any “subversive” academics, and professors at the University of New Hampshire were forced to take a loyalty oath. Paul Sweezy, an economist, lectured at the university and was then investigated by the attorney general for potentially teaching “dialectical materialism,” the 20th-century version of transubstantiation. When Sweezy refused to specify what he had taught in his lecture, he was found guilty of contempt of court. On appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, his conviction was overturned, and Sweezy v. New Hampshire went down in history as a vindication of the independence of higher education.

It behooves everyone at Grinnell College right now to reread this case and, in particular, the two opinions supporting Professor Sweezy. Here is an excerpt from the judgment rendered by Chief Justice Earl Warren — that great Republican governor of California! — which was joined by Justices Hugo Black, William O. Douglas, and William Brennan:

“The essentiality of freedom in the community of American universities is almost self-evident. No one should underestimate the vital role in a democracy that is played by those who guide and train our youth. To impose any straitjacket upon the intellectual leaders in our colleges and universities would imperil the future of our nation … Scholarship cannot flourish in an atmosphere of suspicion and distrust. Teachers and students must always remain free to inquire, to study and to evaluate, to gain new maturity and understanding; otherwise, our civilization will stagnate and die.

“Equally manifest as a fundamental principle of a democratic society is political freedom of the individual. Our form of government is built on the premise that every citizen shall have the right to engage in political expression and association. This right was enshrined in the First Amendment of the Bill of Rights … History has amply proved the virtue of political activity by minority, dissident groups, who innumerable times have been in the vanguard of democratic thought and whose programs were ultimately accepted. Mere unorthodox or dissent from the prevailing mores is not to be condemned. The absence of such voices would be a symptom of grave illness in our society.”

And here is an excerpt from the concurring opinion by Justices Felix Frankfurter and the great conservative icon John Harlan:

“When weighed against the grave harm resulting from governmental intrusion into the intellectual life of a university, [the] justification for compelling a witness to discuss the contents of his lecture appears grossly inadequate … Progress in the natural sciences is not remotely confined to findings made in the laboratory. Insights into the mysteries of nature are born of hypothesis and speculation. The more so is this true in the pursuit of understanding in the groping endeavors of what are called the social sciences, the concern of which is man and society. The problems that are the respective preoccupations of anthropology, economics, law, psychology, sociology and related areas of scholarship are merely departmentalized dealing, by way of manageable division of analysis, with interpenetrating aspects of holistic perplexities.”

“For society’s good — if understanding be an essential need of society — inquiries into these problems, speculations about them, stimulation in others of reflection upon them, must be left as unfettered as possible. Political power must abstain from intrusion into this activity of freedom, pursued in the interest of wise government and the people’s wellbeing, except for reasons that are exigent and obviously compelling … This means the exclusion of governmental intervention in the intellectual life of a university. It matters little whether such intervention occurs avowedly or through action that inevitably tends to check the ardor and fearlessness of scholars, qualities at once so fragile and so indispensable for fruitful academic labor. “

I would underscore how both Warren and Frankfurter describe the gaining of “understanding” as constituent of university life and, according to Frankfurter, “an essential need of society.” Yes, society needs to understand how nature works, how people behave, how art gets created, how cultures work, how ideas are conceived — and the pursuit of this understanding should be protected from government intrusion.

Note how Warren and Frankfurter suggest that such intrusion can be done indirectly through “an atmosphere of suspicion and distrust” or “action that inevitably tends to check the ardor and fearlessness of scholars.” There doesn’t need to be a warrant for a faculty member’s arrest for a college or university to have its intellectual mission — that is, its public service — compromised.

So, as Grinnell College faces potential threats to its mission by federal or state government authorities, may we listen to the voices of the past that exhort us to stay strong. May all of us be as brave, as confident and as victorious as Paul Sweezy. And Wei-Chen O’Leary.