In the Bucksbaum Center for the Arts, 3,992 orange and manila toe tags populate a map of the Arizona-Mexico border. Some of the tags bear handwritten names and ages. Others say “skeletal remains” and “unidentified.” On the other side, messages like “descansa en paz,” Spanish for “rest in peace,” and “you are remembered” convey respect for the deceased.

The exhibit, “Hostile Terrain 94,” highlights the human impact of U.S. border policy. Created collaboratively by faculty, students and community members, the exhibit’s tags represent every migrant who has died trying to cross the Arizona-Mexico border from the mid-1990s to May 2023. The display examines the effects of the Prevention Through Deterrence policy (PTD), implemented in 1994, which redirected migrants to perilous routes like the Sonoran Desert.

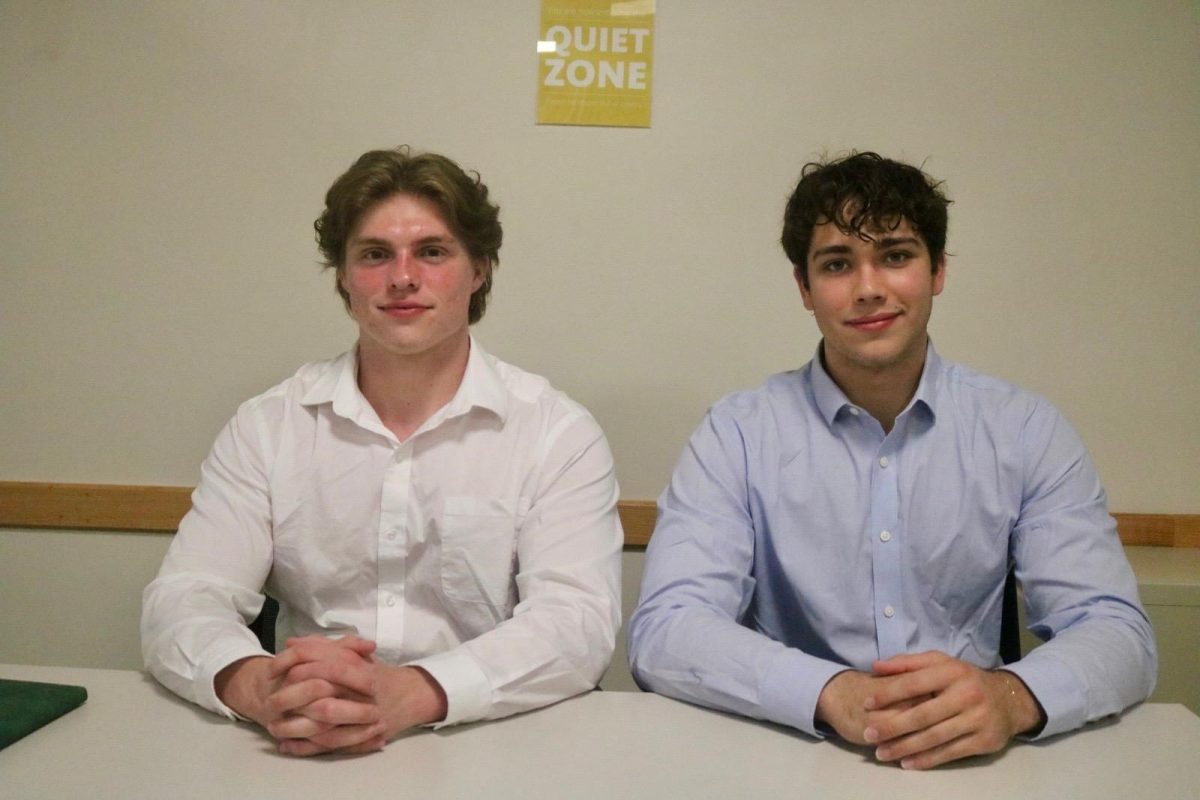

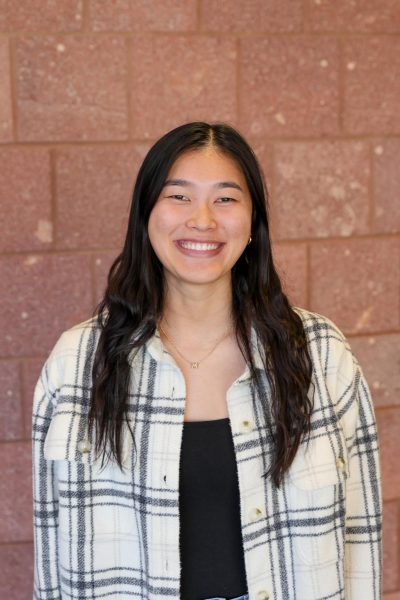

The exhibit was completed on Nov. 7 and will remain on display until May 2025. It was led by Assistant Professor of Anthropology Laura Ng, alongside Associate Professor of Sociology Xavier Escandell, Professor of Anthropology Maria Tapias, and anthropology majors Jorge Salinas ’26 and Kayleen de Loera ’27.

“To see this congregation of human suffering so localized to this very specific point, it has to be transformative,” Escandell said.

Grinnell’s display is part of a traveling exhibit directed by University of California, Los Angeles anthropologist Jason De León, whose book “The Land of Open Graves: Living and Dying on the Migrant Trail” explores PTD’s deadly consequences. Over six million migrants have attempted the crossing, with thousands dying from dehydration and hypothermia.

Escandell explained, “The state uses the desert as a mechanism of killing people in a very intentional way. That’s the main argument of the book.”

Ng hopes the exhibit challenges misconceptions about undocumented migrants. “Whatever we do hear about the border, it’s negative,” Ng said. “There’s too many people coming, but you don’t care about people who’ve died trying to come here … people come here and survive this harsh journey. They’re not here to commit violent crimes.”

Salinas, whose family immigrated to the U.S., said his personal experiences motivated him. “At Grinnell College, especially at a predominantly white institution, it’s not common to get the perspective of the product of immigrants. I think it’s very important, especially with the contributions that are made by immigrants, particularly in agricultural services and the food industry.”

Salinas emphasized the human impact. “They’re not just numbers,” he said. “They’re not just a problem. These are lives.”

To further dialogue, Salinas and Liz Zamarripa `26 hosted a screening and discussion of the documentary “Border South” by Raul O. Paz-Pastrana, which Salinas called a prequel to “The Land of Open Graves.” Reflecting on the recent election, he said, “It’s up in the air … what’s to happen with the lives of migrants and the immigrants that have started lives here. That’s really what’s driving me to continue advocating for this project, advocating for my family and my community.”

Ng raised $3,500 from the Anthropology Department for the project, with the Rosenfield Program and the Center for the Humanities each contributing $1,000 for the exhibit kit. The team built a custom frame to host the map, filled out toe tags with information about deceased migrants, and pinned them at the geographic locations where remains were found.

“We spent hours and hours on just one square,” Ng said. “One six-by-six-inch square could have 170 deceased individuals, and that would take two to three hours. It was a lot of work.”

Around 400 participants — including students, church groups and community members — dedicated 100 hours to filling out tags. Professors also incorporated the project into their classes. “That was also really special and meaningful that they took the time to change their lesson plans so that they could have students participate in the exhibit,” Ng said.

Escandell recalled writing a tag for Maricela, a migrant chronicled in “The Land of Open Graves.” “You go into so much depth on that particular case, but then we have almost 4,000 cases that are equally compelling stories,” he said. “It’s just that they’re not told. For me, that comparison … that’s powerful.”

About half the tags represent people whose skeletal remains are unidentified. DNA analysis is the only way to reunite the deceased with their families. Avajane Lei `28, who worked on the project, described the exhibit’s completion as deeply emotional. “Professor Ng and Professor Escandell pinned the last two tags, and we all stood back for a while. It was quiet,” Lei said. “It felt like we were having a moment of silence for the people who died.”

Escandell calls for accountability through the exhibit. “Some of these migrants leave their home countries because the US was part of the problem or the conditions that create their migration. We have some responsibility,” he said.

On Oct. 29, the advocacy organization Immigrant Allies of Marshalltown visited the exhibit to share their stories. “The Marshalltown immigrant allies event was really important to us to highlight that there are immigrant communities close by, even though Iowa is always known as a really white state,” Ng said. “Marshalltown is our closest huge immigrant community, and we need to get to know them better so we can support them.”

For his global ethnography class, Escandell compared migrant deaths at the U.S.-Mexico border with other border zones, such as Morocco and Spain. “This is a story that is not unique,” he said. “It’s connected to lots of different border zones, and it feels like we need to start thinking systemically … We need real change, not the kind of change embraced by the Trump administration.”

Ng hopes “Hostile Terrain 94” sparks meaningful conversations. “We need immigration reform in a way that is humane,” she said.

Ultimately, the exhibit is more than a memorial. “Working on this project was almost a form of resistance,” Escandell said. “Sitting there and repeating for hours and hours was, for me, a form of … activism.”