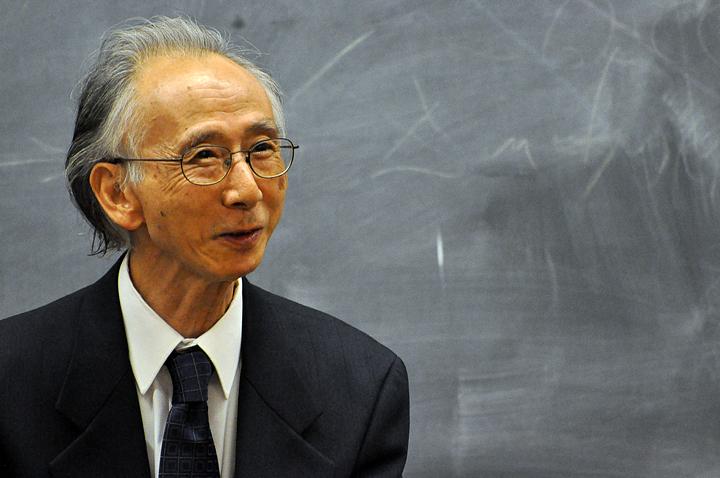

On Tuesday, Nov. 2 in ARH 102, Seiichi Makino, Professor of East Asian Studies at Princeton University, delivered a presentation on “What will be lost in translation? A cognitive linguistic analysis.” He discussed three topics: “What is obviously lost in translation,” “Cases where it is hard to grasp whatever is lost in translations, grammar and culture” and “Translation and Japanese Language Education.” Following the presentation, he sat down with Darwin Manning of the S&B to answer some questions.

Why is the topic of your presentation an issue that college students should consider, what is its application to an average person not involved in translating?

If you have taken any course on literature in translation or if you have read any translated literary work, my talk will make you think hard about what will be lost in the process of translating the original language into English (or into any human language), and should give you motivation to study the original language. I wanted to show that translation is always crucially imperfect, because it is usually impossible to translate the underlying cognitive expressions of the original language, unless you are dealing with two typologically similar languages.

What current research are you conducting?

My research is based on the so-called “cognitive linguistics” that deals with a question of how a native speaker/writer of any human language perceives a given situation. The fundamental ways in which native speakers/writers of any language cognitively understand a given situation are essentially the same. In other words, we share universal cognition. Even so, each language has distinctive characteristics. So my linguistic research always involves the search for both universal and language-specific features.

What was the most challenging part of putting together “A Dictionary of Advanced Japanese Grammar”?

The challenging part has been the same for the three volumes, i.e., “A Dictionary of Basic Japanese Grammar”, “A Dictionary of Intermediate Japanese Grammar” and “A Dictionary of Advanced Japanese Grammar.” It has been most challenging for my co-author and myself to come up with a “simple” generalization for a given grammar. But in our efforts to reach that simple generalization we spent many, many hours in discussion. But the users appear to love the trilogy.

Who would you say are your greatest influences with your work?

I would say that Noam Chomsky’s most insightful philosophy of language led me to think about human language first and foremost in universal terms. Roman Jakobson and Edward Sapir impressed me with their expansive and border-crossing views on human language as well.

You talked a lot about metaphors, and how they are not always translatable. Do you think you can reiterate what your main point regarding this was?

In translation the majority of creative metaphors will not be lost in translation, because as the current brain science is showing, we humans universally use three types of metaphors (i.e., the ones based on analogy, inclusion and contiguity), but highly idiomatic metaphors are definitely lost in translation. The most important part of metaphors is that they serve to represent our cognitive skills to characterize a target object using one of the three metaphorical means.

Claude Morita • Jul 22, 2013 at 1:16 am

In my very humble opinion, one Japanese kanji has history, culture, dozens of choices, and implied meanings. English seems much too limited for expressing any of the meanings because of its “logic.” Please do not “retire” from promoting understanding.