How does it feel to write in a foreign language? Not an application, not a CV, not a letter to a pen friend, but a free, creative, literary text?

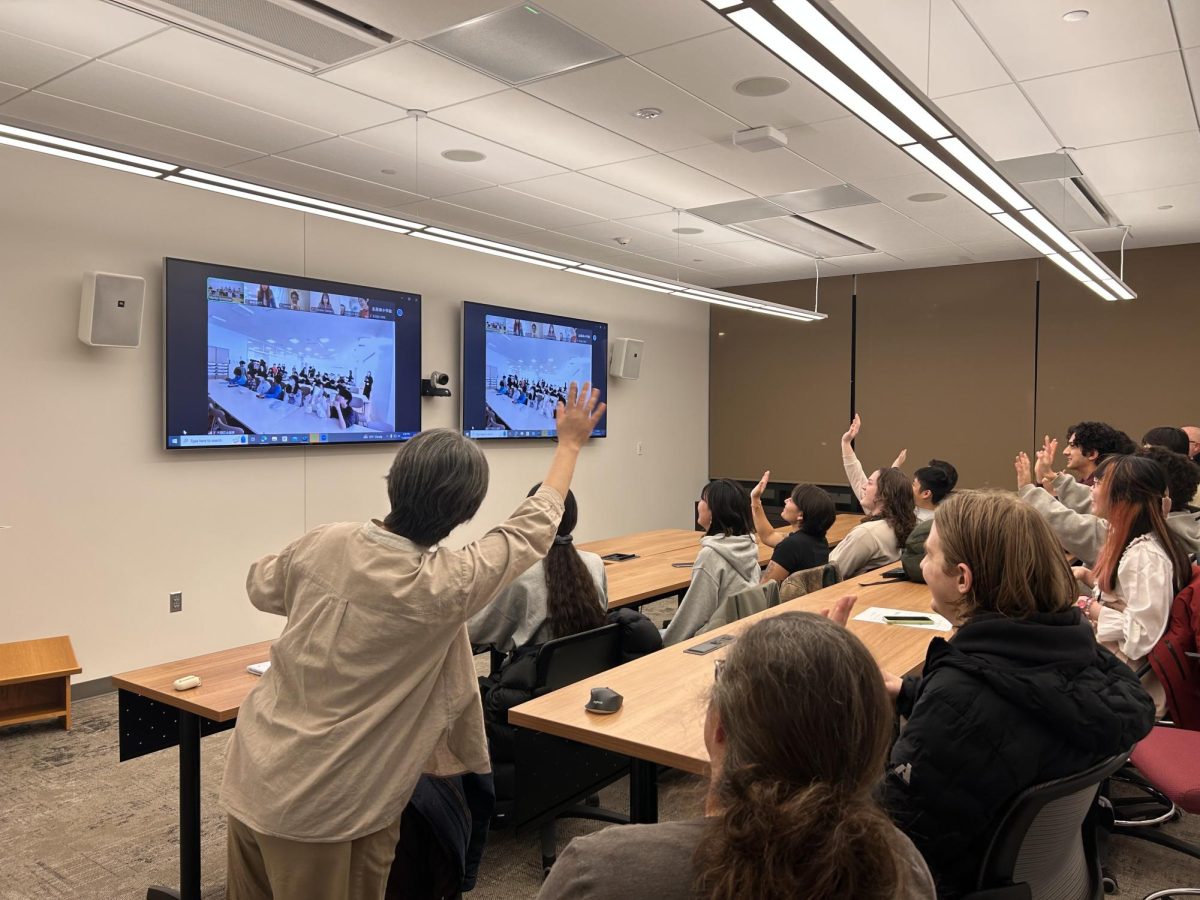

Learning German is a tough job. Three genders, four cases and the resulting jumble of endings, plus other grammatical peculiarities, are not easy to handle. In the spring term, seven brave students faced up to the task for GRM-372: Creative Writing in German. They met on Monday evenings – “full of strange D-Hall fodder,” as one of them wrote in a poem – to explore new horizons of expression with me, the Writer in Residence of 2024. We were working on technical problems like narrative perspective and tenses, but also did warm-ups — “Fingerübungen”, like on the piano — in the form of little poems. In answers to our introductory question, the students described the task as “difficult,” their state of mind as “nervous” and “insecure,” and the foreign language as “resistant.”

As a professional literary translator with the working languages English and Chinese, I am especially interested in writers who write in a language which is not their mother tongue––I specialize in translating (into German) Chinese authors, who write their novels in English, thereby listening to the faint traces of Chinese syntax and wording in their English texts.

Choosing a foreign language as a means of literary expression can have many reasons and happens not always of free choice. Some have to leave their country because of political pressure, some want to reach a wider public, some make this change of linguistic mindset their special literary program — like Jhumpa Lahiri, the Pulitzer Prize-winning American writer of Indian-Bengali origin, who stopped writing in English and changed to Italian, a language she learned in adulthood. I got to know her work, by the way, through one of my students.

Most of these writers describe it as a liberating experience, broadening their linguistic awareness and giving them a new mindset. Perfect prospects for plunging into the adventure of writing in a foreign language.

Meanwhile, I found myself in the middle of an interesting self-experiment as well. My own novels are dealing with cultural contrasts and clashes — so far mainly between Germany and China. Having learned Chinese and lived and taught in a Chinese environment for a couple of years, I almost exclusively traveled east and found my exotic experiences there. But this time, I changed direction and followed an invitation to Iowa, and my antennae for this new experience were set.

Even in a culture where my appearance did not mark me as a noticeable stranger, and which shares common cultural roots with my own, one can be confronted with foreignness. How to deal with the friendly comments of complete foreigners on the color of my trousers or my haircut? Are people who are inquiring about my wellbeing expecting an honest answer, or is that just a form of greeting? It astounded me that in the changing room and showers of the swimming pool, women reacted ostensibly shy to the nakedness of their own sex. And finally, I found out that even American rodents have their culture-specific tastes — in mouse traps, they seem to prefer peanut butter over the typically German bait of cheese.

Leaving my old routines behind and settling in a new environment, language, working context and everyday life, I observed with fascination at what point the unfamiliar became familiar. When did I reach the tipping point, where acute awareness was dulled by habit? When did I lose the special alertness and sharpness of observation, which is so typical for a foreigner and so precious to a writer?

There we were: students and teacher, exploring new territory. Each Friday I was looking forward to their texts piling up in my e-mailbox, every Monday to discussing those achievements and introducing a new aspect of writing and preparing the next task. With their limited linguistic means, the students created wonderfully funny, but also deeply emotional texts, and set their punchlines with panache. All seven of them lasted until the end — secretly I called them my Seven Uprights.

I am deeply grateful to the German Studies Department of Grinnell College for this opportunity. I got to know a wonderfully diverse place of learning and gained a lot from this experience. In order to give back, I wrote this little article in a foreign language. Now I submit it to the sharp eyes of the editors. As for The Scarlet & Black — this forever daunting color combination of a text coming back from a teacher or editor — I do hope for rather more black than scarlet.