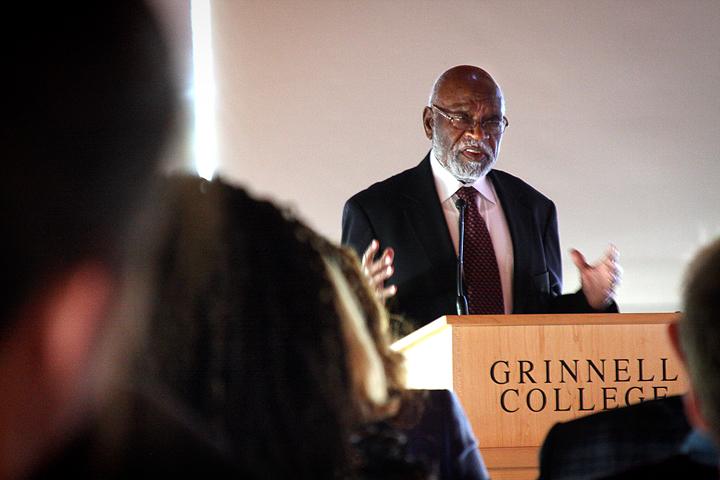

Dr. Andrew Billingsley ’51 is a professor of sociology and African-American Studies at the University of South Carolina. He has also served as the President of Morgan State University and as the Vice-President of Academic Affairs for Howard University. He is the author of several books including the very influential Black Families in White America. Jai Garg of the S&B sat down with Billingsley to discuss his life at Grinnell and his views on the field of sociology.

What are some of the significant changes that you have noticed at Grinnell since you were a student until now?

The physical changes are phenomenal. I can hardly figure out where the old campus was, I keep looking for the men’s dormitories and women’s dormitories and the space in between. The physical development of the campus has been fantastic and almost unrecognizable.

How would you characterize the changes in the student body? Has Grinnell been living up to what it touts as its institutional goals?

Liberalism is still very strong and diverse at the college—student living arrangements is one example of that. Co-ed dorms and so on shows that people are adults and can take care of their personal affairs. I can’t tell about the organizational life of the college, but it seems to be more vigorous than it was, a little bit more laid back when we were there in the 50’s. The students [that we met] seemed bright as ever, Grinnell has always had bright students, but also more committed to the wider world outside of Grinnell and not as insulated as we were in the 50s. The faculty that we have seen, seem to have very good and close relationships with the students, the faculty student relationships have been on display for us the last two days and its very impressive. The faculty really cares about the students…

And finally I met the president today and the impressive thing about the president’s office is that it wasn’t impressive. It wasn’t like a big desk and sitting behind it, he was actually working on a table. The department of the president offers another example of Grinnell’s strong tradition of openness and humanitarianism and willingness to do new things. There is long strain of history going from the founding of the college by abolitionists to today’s celebration of us and welcoming us in Grinnell’s spirit of humanitarianism, it’s very impressive.

Could you recount your first experience at Grinnell?

My first visit to Grinnell was as an exchange student in January 1949. I was terribly impressed by the cold weather—I got strep throat and had to go to the hospital for five days. But at the same time, I wasn’t afraid I didn’t feel like I was in a strange place, the teachers and students were looking after me. So I just lay in the hospital until I was cured and came on back. There has always been, in my opinion, a strong connection between the faculty and the students and I guess that a characterization of a small liberal arts college. And there was the Political Science faculty who would meet with us and tell us about the world. Professor Willhelm was always open to the students and we just reveled in that. After that first experience in the cold weather, after I came back as a regular student, I adapted to it. The Grinnell experience was very warm and inviting.

How was it being a copy editor on the S&B?

Kay Schwartz discovered me and invited me to come work on the board of the paper. It was a very comfortable experience, I think I was more gregarious then I am now. I wrote one or two columns, I did the copyediting and the headings and we had staff meetings. It was a great learning experience for me, I had not done it before but I felt very comfortable.

As someone who brought a monumental change to the field of sociology, do you think that the field at major academic institutions represents a variety of perspectives or is there still a Eurocentric perspective present?

Sociology and Political Science and History and Anthropology and maybe even Musicology have made tremendous strides in including diversity of humanity across the world. But the institutions, the universities and maybe even the colleges, have not been that embracing. There is still a bit of cutting edge scholarship going on to cast the complexity of the world. For example, the University of South Carolina is in South Carolina but there are a lot of aspects of South Carolina history that aren’t part of the University of South Carolina’s history. I wouldn’t be surprised if there are aspects of Iowa history that is not part of the Grinnell experience. So institutions are slow to adapt to changing situations in race and community but there is still a wedge between campus and community at colleges and universities. A lot of work needs to be done still pushing institutions.

We at South Carolina are part of a movement among faculty and students to have the university reach out and recognize the damage to these communities, so there is still a lot of work to be done, cutting-edge work. And … students are likely to be the key to what institutions do to raise other people’s awareness of other parts of the world. Students ask questions, students want to know and sometimes students want to decide.

When students come to college, the college opens up fantastic vistas for them. So sometimes students use that to push the college, like in the Black Studies, Asian Studies and Hispanic studies days at Berkley. Students came to the university, so the university gave them classes, classrooms, places to sleep and dining rooms. They used these means to expand the University to move the university, reluctantly sometimes, into to new areas of academic, social, and humanitarian scholarship.

If you had not gone into academia, what other field could you see your self in?

I thought coming out of Grinnell, I wanted a government career. I had been dissuaded by Dr. Willhelm. Public service, government, it was an overload as I was going into the ministry and I was dead determined. That’s what I got from Grinnell, that’s what I was going do? And so that was my call, I was trained to do that but then religion interfered with that, my religious calling [to Quakerism], so when the Quakers said, we need you to come to Chicago to help us get more college students involved in programs. Wow, that’s even better than the government, so I did that. But I thought it was a temporary lead to it because all Quaker work is temporary. So I missed that opportunity to go into government but I didn’t give up.

Would you like to add to anything you haven’t already said to our readers?

I think my experience at the S&B…I had never done anything like that before. In fact, I had not written much. When I went to college in Hampton, I never read anything more than a page in high school so it was a struggle for me to write long things, but at the S&B I could write short things…and that set me off in a way that I even considered doing newspaper work for a long time. But it’s amazing how you go through life, you don’t always plan out your trajectory through life and things happen sometimes. At the time, you would have thought, well I’m head of the NAACP and I’m traveling all around. What’s this little job? Copy Editor of the S&B? But it had it’s price and it helped shape me and I turned out to be good enough at writing that I could not only write a whole essay but a whole book.