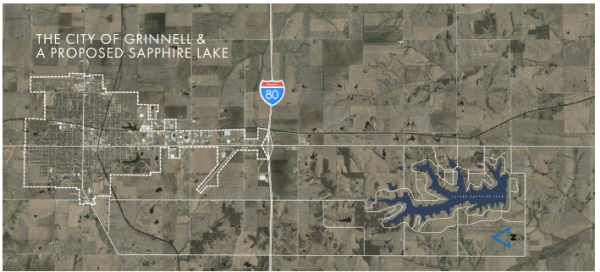

Plans are underway to build Sapphire Lake, an over $650 million project featuring a 1000-acre development complete with a 380 acre artificial lake south of Grinnell. However, the colossal plan, projected to support 3,681 jobs and a $400 million increase in the property tax base, has yet to meet its funding goal and has proven to be a divisive topic for local residents.

Undertaken by the City of Grinnell and Poweshiek County (both of which make up the local government) in partnership with McClure Engineering, a civil engineering consulting firm, and ATI Group, a sister company to McClure Engineering, the project involves building natural trails, camping grounds, fishing areas and parks that will be available for public use, said Russ Behrens, Grinnell City Manager.

Furthermore, the development would also include 700 to 750 housing units, 500 of which are planned lakefront properties, said Terry Lutz, Chairman of McClure Engineering.

“Without it, I think we’re on a path to just shrivel up and be like a lot of small towns around us,” said Randy Hotchkin, a Grinnell resident who thinks the lake would be “a great asset to the community.”

According to census data, rural communities in Iowa have indeed been experiencing a population decline for the majority of the past 110 years.

“I think it’s worth the gamble,” Hotchkin continued. “Because we really are losing a lot [of restaurants] and there’s not any indications that we’re going to gain any more restaurants or entertainment.”

John Ashby, a Grinnell resident, said he had concerns with the project, primarily, on what would happen if the development were to stop for any reason. He said his concern stems from the fact that if the local government issues the debt for the project, it would still be responsible for paying the debt and its interests even if the project falls through.

Ashby was also dissatisfied with only approximately 11% of the shoreline being available to the public, according to his rough estimates. The remainder of the shoreline would be part of the lakefront properties. “That just doesn’t even seem remotely reasonable to me,” he said.

Behrens shared a different sentiment on that figure, and said that having 11% percent of the shoreline be open to the public “is meaningful when there’s so much shoreline.”

“This is a really big lake. The shoreline, of course, is the most valuable property here, and that’s what ultimately funds the public investment and the private investment, because that’s where the property tax revenue is being generated.”

Scott Gruhn, a Grinnell resident, said, “At first I was hesitant about it. My one concern was taking farmland out of production.”

Behrens said that the proposed land is not all farmland, and that “it’s 100% voluntary. There is no force that can be exerted on these landowners to sell their property.”

Both Diamond Lake and Otter Creek Lake are Iowan lakes that have had different environmental sediment build-up issues in recent years and have been restored.

Lutz said that the developer is taking precautions to help avoid similar environmental issues.

The developer plans on building floor beds, which are small holding ponds upstream of the lake used to capture water coming into the drainage basin so that the silt settles before reaching the lake, said Lutz. Additionally, the developer will use stream bank stabilization – a process where native vegetated grasses are planted – above the lake to move the slopes back on the bank to minimize erosion and silt, he said.

This project has been in the works for the past couple of decades, with its previous iteration falling through due to it being unable to secure adequate funding at the time, said Behrens.

“I think one of the reasons [the project] didn’t form previously was there’s so much investment that needs to take place up front – buying the land, building the dam, all the professional services work that needs to occur – that no developers are willing to take that on in a relatively small rural community,” said Behrens.

“So one of the pivots we’ve made is, in all previous renditions of this project, it has been posed as a private development, which means that unless you live out there, you cannot use this recreational asset,” added Behrens. “The city has never supported the central part of development. We have always pushed for this to be a public asset for the community. And the current developer has bought into that concept.”

The lake, if complete, will be managed jointly by the city and the county. The camping grounds, however, will be managed solely by the county because it is “not a skill set” the city has right now, according to Behrens.

In the best case scenario, the project would break ground in a year, said Behrens, however, a more realistic estimate is 18 to 24 months from now. The construction of the housing units is expected to take 10 years, according to the economic impact analysis of the project, and the construction on the lake would begin either in late 2025 or in 2026. Construction is expected to be completed by the end of 2026.

A project like Sapphire Lake would require a substantial investment from the local government and the developer. According to the economic impact analysis of the project, the investment required by the local government would be either $22 or $32 million, depending on whether the local government is able to secure the $10 million Iowa Destination Grant from the Iowa state government, according to the economic impact analysis.

The Iowa Destination Grant is part of a program which has been “designed to bolster the quality of life in Iowa’s communities and attract visitors and new residents to the state.” However, this grant will not be approved until the city and county governments are able to demonstrate local financial support for the project, said Behrens. He said the local government is making good progress on this component and could potentially release further information in the upcoming weeks.

Regardless of whether the local government is granted the $10 million, it will be responsible for some initial investment which may be in the form of issuing debt to finance its investment, said Behrens. However, as the project advances and revenue is generated through property taxes, the project will use the revenue to retire the debt – a process called Tax Increment Financing (TIF) – said Behrens.

The investment made by the local government will go towards building the initial infrastructure for the project, like sewers, running water and the construction of the lake itself, said Behrens.

The project’s economic impact analysis shows several areas of economic growth, including the nearly $651 million that would be pumped into construction as well as a projected population growth of 362 people. The project is expected to support roughly $60 million in tax increment financing (TIF) revenue and $13 million in new resident spending among other metrics.

Under the Urban Renewal and Tax Increment Financing code, high-end housing projects that use TIF as a means of funding must set aside a portion of the tax revenue to benefit low- to moderate-income families. According to the economic impact analysis, the local government must set aside a maximum of $6.5 million. Behrens said that the revenue does not need to be spent on the housing for the lake but can be used for multiple purposes, such as improving infrastructure in low-income neighborhoods.

“So that’s one of the really interesting benefits of this project, too, is that it has that requirement attached to it,” Behrens said.

Behrens also noted that if the population does grow as a result of the project, it would mean that the price of certain services with fixed costs – like emergency service responses – would decrease because they are spread over a larger tax base. If Grinnell residents buy properties at the lake and sell their own homes, there would also be added potential for less-expensive housing options to become available as well.

“Just in an effort to revitalize a town, I think it needs some kind of draw like that … I’ve been back about 10 years, and we’ve definitely lost more than we’ve gained. That’s kind of frustrating,” said Hotchkin.

Behrens wrote in an email to the S&B that all incentives – referring to the investment by the local government – will be governed by an agreement with the developer which will lay out the responsibilities of each party, and that this type of agreement usually has benchmarks and requirements that must be met before the investment is made. He also wrote that the agreement has not yet been drafted.

Ashby said he was also concerned with the current state of the economy and the high interest rates on mortgages that the country has experienced in recent years which would make selling the housing units much more difficult, affecting the local government’s ability to collect revenue from the development.

The historical average of 30-year mortgage interest rates in the United States is 7.74 percent according to Trading Economics, while the current interest rates lie at 7.79 percent according to Federal Reserve data. The interest rates are returning to the historical average after being relatively low in the decade prior to COVID. Interest rates are projected to decrease to approximately 6 percent during 2024 according to Wells Fargo, Fannie Mae and Mortgage Bankers Association.

Lutz said that the developer does not expect to start building housing units until 2026.

Behrens said that the local government has done a market analysis which shows “tremendous demand for lakefront properties in Iowa and the Midwest,” and that there are 1.3 million people who live within a 60-minute drive of Grinnell.

Ashby said he was concerned that the local government will not be able to generate revenue from the development until the housing units are complete. However, Lutz said that prior to the building of the housing units, the developer will try to sell lots in 2026 and potentially 2025 to individuals who wish to build their own homes, and that the housing units will be built in phases, starting with the lakefront properties.

Ashby also said he was concerned that if the project deviates from the plan, the project may lose the Iowa Destination Grant.

Yet, Behrens insisted that “having done hundreds of grants with the state, they’re pretty good about working with us.” He said that he is confident that as long as the project remains public access, the Iowa government would be willing to work with the local government.